Mars. Image credit: NASA/JPL

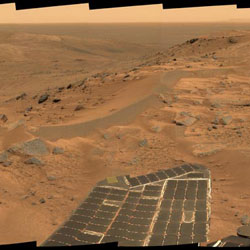

Monday, October 17 – Did readers on the West Coast get a chance to see the partial lunar eclipse this morning? Excellent, because the Full Hunter’s Moon will make “hunting” most deep sky objects next to impossible tonight. But who cares when you can see Mars in such great detail!

Is it really that good and really that worth the wait for it to rise? The answer is yes. Even through a small telescope it is very easy to see the dark markings and the brilliant polar cap. Although Mars won’t rise for good viewing until late evening, don’t wait any longer to start your observations. In larger telescopes at higher powers, you will see Mars as you have never seen it before. Even if you do not use a telescope, you cannot miss this huge, bright, reddish planetary disc rising in the east.

Want a map? Care to sketch? Or would you just like more details? Then you’ll find no site more comprehensive than the Association of Lunar and Planetary Observers. This ALPO page contains everything you’ll need to tun this year’s “Mars Experience” into the best you’ve ever had!

Tuesday, October 18 – Today in 1959, Soviet Luna 3 began returning the first photographs of the Moon’s far side. Also today – but in 1967 – the Soviets again made history as Venera 4 became the first spacecraft to probe Venus’ atmosphere. Unlike Mars, Venus shows little details but it’s still a fine way to start the evening. Look for its bright, phasic disc just west of Sagittarius after sunset.

If you’d really like to see some details, try looking at the lunar surface tonight and focus your attention towards the stretched oval of crater Gauss located about midway on the northern quadrant of the eastern limb. With the terminator so near, can you see four southern interior craters? Move further south and central on the limb. Mare Smythii might be gone, but look at small, overlapping craters Jenkins and Nobili.

Wednesday, October 19 – For viewers in Spain, Portugal, Italy and Greece, you have a very rare and exciting event this morning! Asteroid Rhodope will eclipse bright star – Regulus. While this event requires no special equipment, your observances could make a significant contribution to the folks at the International Occultation and Timing Association (IOTA). Please take the time to visit this page for details on how you can help scientific studies. An event like this won’t happen again until 2014… Please watch. Wishing you clear skies!

For viewers in the United States and Canada, tonight is a definitely celestial gathering as the Moon, Mars and the Pleiades will make a wonderfully tight trio as the come up in the east, and this would be a great night to explore!

While we’re waiting on them to rise, let’s have a look in Cassiopeia at two of its primary stars.

Looking much like a flattened “W” the southern-most bright star is Alpha. Also known as Schedar, this magnitude 2.2 spectral type K star, was once suspected of being a variable, but no changes have been detected in modern astronomy. Binoculars will reveal its orange/yellow coloring, but a telescope is needed to bring out its unique features. In 1781, Sir William Herschel discovered a 9th magnitude companion star and our modern optics easily separate the blue/white component’s distance of 63″. A second, even fainter companion at 38″ is mentioned in the list of double stars and even a third at 14th magnitude was spotted by S.W. Burnham in 1889. All three stars are optical companions only, but make 150 to 200 light year distant Schedar a delight to view.

Just north of Alpha is the next destination for tonight – Eta Cassiopeiae. Discovered by Sir William Herschel in August of 1779, Eta is quite possibly one of the most well-known of binary stars. The 3.5 magnitude primary star is a spectral type G, meaning it has a yellowish color much like our own Sun. It is about 10% larger than Sol and about 25% brighter. The 7.5 magnitude secondary (or B star) is very definitely a K-type, metal poor, and distinctively red. In comparison, it is half the mass of our Sun, crammed into about a quarter of its volume and around 25 times dimmer. In the eyepiece, the B star will angle off to the northwest, providing a wonderful and colorful look at one of the season’s finest.

Thursday, October 20 – Tonight is one of the busiest night skies of the year. We are now slipping into the stream of Comet Halley and into one of the finest meteor showers around, but the Moon is going to play a very major role through tonight and tomorrow morning.

For viewers in the southern part of Europe and the northern portion of Africa, you will have the chance to watch the Moon occult 27 Taurii tonight. Be sure to visit this IOTA webpage for charts and times in your location.

If you should happen to live a little more centrally in Africa, or in South America, it just gets better as the Moon will coast through the Pleiades star cluster on this date for you. Thanks to the good folks at IOTA, you can use this reference material for more specific details. Clear skies!

Friday, October 21 – Be sure to be outdoors before dawn to enjoy one of the year’s most reliable meteor showers. The offspring of Comet Halley will grace the early morning hours as they return once again as the Orionid meteor shower. This dependable shower produces an average of 10-20 meteors per hour at maximum and the best activity begins before local midnight on the 20th, and reaches its best as Orion stands high to the south at about two hours before local dawn on the 21st.

Although Comet Halley has long since departed our Solar System, the debris left from its trail still remain scattered in Earth’s orbital pattern around the Sun allowing us to predict when this meteor shower will occur. We first enter the “stream” at the beginning of October and do not leave it until the beginning of November, making your chances of “catching a falling star” even greater. These meteors are very fast, and although they are faint, it is still possible to see an occasional “fireball” that leaves a persistent trail.

Clouded out or the Moon too bright? Don’t worry. You don’t always need your eyes or perfect skies to meteor watch. By tuning an FM radio to the lowest frequency possible that does not receive a “clear signal”, you can practice radio meteor listening. An outdoor FM antenna pointed at the zenith and connected to your receiver will increase your chances, but it’s not necessary. Simply turn up the static and listen. Those hums, whistles, beeps, bongs, and occasional snatches of signals are our own radio signals being reflected off the meteor’s ion trail!

For viewers over most of Australia, be sure to keep an eye on the sky tonight as the Moon will occult bright Beta Taurii for most locales on this universal date. Be sure to check IOTA for more specific details.

Saturday, October 22 – Something very special happened today in 2136 B.C. There was a solar eclipse and for the very first time it was seen and recorded by Chinese astronomers. And probably a very good thing because royal astronomers were executed for failure to predict!

Today is also the birthday of Karl Jansky. Born in 1905, Jansky was an American physicist as well as an electrical engineer. One of his pioneer discoveries were non-Earth based radio waves at 20.5 MHz while investigating noise sources between 1931 and 1932. And, in 1975, Soviet Venera 9 was busy sending Earth the very first look and Venus’ surface.

Thanks to just a slightly later rise of the Moon, let’s return again to Cassiopeia and start first by exploring the central most bright star, Gamma. At approximately 100 light years away, Gamma is a very unusual star. Once thought to be a variable, this particular star has been known to go through some very radical changes with its temperature, spectrum, magnitude, color and even diameter. Gamma is also a visual double star, but the 11 magnitude companion is highly difficult to perceive so close (2.3″) from the primary.

Four degrees southeast of Gamma is our marker for this starhop, Phi Cassiopeiae. By aiming binoculars or telescopes at this star, it is very easy to locate an interesting open cluster, NGC 457, because they will be in the same field of view. This bright and splendid galactic cluster has received a variety of names over the years because of its uncanny resemblance to a figure. Some call it an “Angel”, others see it as the “Zuni Thunderbird”, I’ve heard it called the “Owl” and the “Dragonfly”, but perhaps my most favourite is the “E.T. Cluster”, As you view it, you can see why. Bright Phi and HD 7902 appear like “eyes” in the dark and the dozens of stars that make up the “body” appear like outstretched “arms” or “wings”. (For E.T. fans? Check out the red “heart” in the center.)

All this is very fanciful, but what is the NGC 457, really? Both Phi and HD 7902 may not be true members of the cluster. If magnitude 5 Phi were actually part of this grouping, it would have to have a distance of approximately 9300 light years, making it the most luminous star in the sky, far outshining even Rigel! To get a rough of idea of what that means, if we were to view our own Sun from this far away, it would be no more than magnitude 17.5. The fainter members of the NGC457 comprise a relatively “young” star cluster that spans about 30 light years across. Most of the stars are only about 10 million years old, yet there is 8.6 magnitude red supergiant in the center.

Sunday, October 23 – With tonight’s early dark skies, let’s take out binoculars and have a look at an old favourite – “The Double Cluster” – NGC869 and NGC884. This pair of rich galactic open clusters rising in the northeast are an unaided-eye object from a dark site, easily seen in the smallest of binoculars from urban locations and beyond compare when viewed with a telescope at lowest power.

The western-most of the pair is NGC869, also known as “h Perseii”. It contains at least 750 stars clustered in a brilliant mass spanning about 70 light years, and approximately 7,500 light years away from us. It’s eastern companion is NGC884, or “Chi Perseii”. The statistics are almost a match, but NGC884 only has about half as many stars – some being “super giants” over 50,000 times brighter than our own Sun. These twin clusters have only one major difference: NGC884 is approximately 10 million years old and the NGC869 is perhaps 5 million. The existance of these splendid clusters was cataloged as far back as 350 B.C. with both Ptolemy and Hipparchus noting their appearance – yet Messier never “discovered” them!

This issue celebrates a full year of appearing on “The Universe Today”. I thank all of you who have taken the time to write and I would love to hear your suggestions for next year. Thank you for reading! Until next week? Ask for the Moon, but keep reaching for the stars! May all your journeys be at light speed…. ~Tammy Plotner