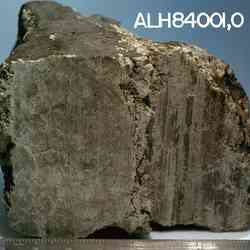

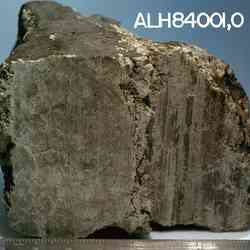

A section of the ALH84001 Mars meteorite. Image credit: NASA/JPL. Click to enlarge

The current mean temperature on the equator of Mars is a blustery -69 degrees Fahrenheit. Scientists have long thought that the Red Planet was once temperate enough for water to have existed on the surface and perhaps for life to have evolved there. But a new study by MIT and Caltech scientists gives this idea the cold shoulder.

In the July 22 issue of the journal Science, MIT Assistant Professor Benjamin Weiss and California Institute of Technology graduate student David Shuster report that their studies of martian meteorites demonstrate that at least several rocks originally located near the surface of Mars have been freezing cold for 4 billion years.

Their work is a novel approach to extracting information on the past climate of Mars through the study of martian meteorites.

In fact, the evidence suggests that during the last 4 billion years, Mars has never been sufficiently warm for liquid water to have flowed on the surface for extended periods of time. Mars therefore has probably never had an environment hospitable to the evolution of life–unless life got started during the first half-billion years of its existence, when the planet was probably warmer.

The work involves two of the seven known “nakhlite” meteorites (named after El Nakhla, Egypt, where the first such meteorite was discovered), and the celebrated ALH84001 meteorite that some scientists believe shows evidence of microbial activity on Mars. Using geochemical techniques, Shuster and Weiss reconstructed a “thermal history” for each of the meteorites to estimate the maximum long-term average temperatures to which they were subjected.

“We looked at meteorites in two ways,” said Weiss, of MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences. “First, we evaluated what the meteorites could have experienced during ejection from Mars, 11-to-15 million years ago, in order to set an upper limit on the temperatures in a worst-case scenario for shock heating.”

They concluded that ALH84001 could never have been heated to a temperature higher than 650 degrees Fahrenheit for even a brief period of time during the last 15 million years. The nakhlites, which show very little evidence of shock damage, were unlikely to have been above the boiling point of water during ejection 11 million years ago.

Those temperatures are still rather high, but the researchers also looked at the rocks’ long-term thermal history on Mars. For this, the scientists estimated the total amount of argon still remaining in the samples using data previously published by two teams at the University of Arizona and NASA’s Johnson Space Center.

Argon gas is present in the meteorites as well as in many rocks on Earth as a natural consequence of the radioactive decay of potassium. As a noble gas, argon is not very chemically reactive, and because the decay rate is precisely known, geologists for years have dated rocks by measuring their argon content.

However, argon is also known to “leak” out of rocks at a temperature-dependent rate. This means that if the argon remaining in the rocks is measured, an inference can be made about the maximum heat to which the rock has been subjected since the argon was first made. The cooler the rock has been, the more argon it will have retained.

Shuster and Weiss’s analysis found that only a tiny fraction of the argon that was originally produced in the meteorite samples has been lost through the eons. “The small amount of argon loss that has apparently taken place in these meteorites is remarkable. Any way we look at it, these rocks have been cold for a very long time,” says Shuster. Their calculations suggest that the martian surface has been in a deep freeze for most of the last 4 billion years.

“The temperature histories of these two planets are truly different. On Earth, you couldn’t find a single rock that has been below even room temperature for that long,” says Shuster. The ALH84001 meteorite, in fact, couldn’t have been above freezing for more than a million years during the last 3.5 billion years of history.

“Our research doesn’t mean that there weren’t pockets of isolated water in geothermal springs for long periods of time, but suggests instead that there haven’t been large areas of freestanding water for 4 billion years.

“Our results seem to imply that surface features indicating the presence and flow of liquid water formed over relatively short time periods,” says Shuster.

On a positive note for astrobiology, however, Weiss says the new study does nothing to disprove the theory of “panspermia,” which holds that life can jump from one planet to another by meteorites. While at Caltech as a graduate student several years ago, Weiss and his supervising professor, Joseph Kirschvink, showed that microbes could indeed have traveled from Mars to Earth in the hairline fractures of ALH84001 without being destroyed by heat. In particular, the fact that the nakhlites have never been heated above about 200 degrees Fahrenheit means that they were not heat-sterilized during ejection from Mars and transfer to Earth.

This work was sponsored by NASA and the National Science Foundation.

Original Source: MIT News Release