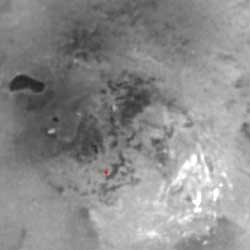

The white dwarf star Gliese 86B is the tiny dot to the left of the bright star. Image credit: ESO. Click to enlarge.

The team has found that a star known as Gliese 86 – part of the southern constellation Erinadus, and just visible to the unaided eye – has another companion in addition to the gas giant planet that was found in a tight orbit around it seven years ago. However, this more distant companion is not another planet, but a white dwarf star that is about as far from Gliese 86 as is Uranus from the sun. The discovery marks the first time a planet has been found in the vicinity of a white dwarf, and could have implications for our own solar system – which will itself be centered around a white dwarf in a few billion years.

“This is the first observational evidence that planets can survive the white dwarf formation process of a star several astronomical units away,” said researcher team member Markus Mugrauer, a doctoral student at the Astrophysical Institute and University Observatory, University of Jena, Germany. “In theory, nearby planets should not survive the formation process, but this finding is evidence that, if they are sufficiently distant, they can. This is of interest because most stars in the galaxy, including our own, will eventually evolve into white dwarfs.”

The study, which Mugrauer conducted with Dr. Ralph Neuhaeuser, director of observations at the university’s astrophysics institute, were published as a letter in the May issue of “Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.”

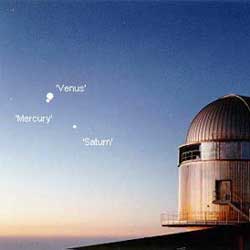

The planet itself was discovered in late 1998 at Switzerland’s La Silla observatory, and was the first exoplanet to be found using a telescope at La Silla that had been fitted with a spectrograph for the express purpose of searching for planets around other stars. Further analysis of Gliese 86’s movements indicated that the star also had a faint stellar companion that had not yet been observed, possibly a brown dwarf — an object with insufficient mass to sustain fusion in its core.

“No one was sure what it was, however,” Mugrauer said. “Just as the planet itself had been found by its influence on Gliese 86 but had not actually been ‘seen,’ the companion was tugging on the star but it was difficult to separate from background light.”

To resolve Gliese 86’s companion, the pair used high contrast observations using the 8m Very Large Telescope at La Silla together with a new simultaneous differential imaging device.

“With these instruments, we can resolve objects about 150,000 times fainter than the central star, but which are still very close to them,” Mugrauer said. “This allows us to search for close and very faint companions of our target stars.”

After filtering out the background noise, they found Gliese’s companion orbiting at a distance of about 21 AU, but were surprised to find it hotter than expected — at least 3700 Kelvin, too warm to be a brown dwarf. Judging by its velocity and distance from Gliese 86, they also found that the white dwarf has about 55 percent the mass of our sun, making it smaller than Gliese 86, which has 70 percent of our sun’s mass.

“But since a star loses a good deal of its mass as it evolves into a white dwarf, this companion was once much larger than Gliese 86, perhaps as large as our own sun or even larger,” Mugrauer said. “It was much closer to Gliese 86 before it became a white dwarf, perhaps 15 AU, or a distance about halfway between the orbits of Saturn and Uranus in our own system. It migrated outward after it lost mass during its evolution into a white dwarf.”

Because of the planet’s size and distance from the red giant, Mugrauer said, the companion’s evolution wouldn’t have dramatically affected the planet’s size.

“The planet’s gravity is simply too strong to lose mass because of the impacting material and due to its large separation,” he said. “However, during the red giant phase, the companion would have swollen up and become 10,000 more luminous. It would also have become the dominant heat source of the planet, heating it 1000K or more.”

Nowadays, he said, the companion would probably appear as a very bright star in the planet’s night sky, but would provide it with very little additional heat in comparison with Gliese 86, which the giant planet circles at about a tenth the distance of the Earth to the sun.

“We expect that distant planets — those farther than Jupiter is from our sun — can survive the evolution of a star from red giant to white dwarf. These observations tend to confirm that expectation,” Mugrauer said. “In the Gliese 86 system in particular, the separation between the white dwarf and the exoplanet is large enough that it seems very possible that a planet can survive the red giant phase of a G dwarf such as our sun.”

But Mugrauer said that he and Neuhaeuser would continue to search for companion stars in this and other exoplanetary systems because, despite the number of planets that have been found circling other stars, little is known about the properties of planets in binary systems. Planets in close binaries, like Gliese 86, are rare. “Gliese 86 is one of the closest binary systems hosting a planet,” Mugrauer said.

“These systems provide important information about the planet formation process and how the multiplicity of the host star may effect it,” he said. “Gliese 86 is only about 35 light years from earth, so it was near the top of our list of stars to explore. But we are on our way to checking out a lot more.”

Written by Chad Boutin