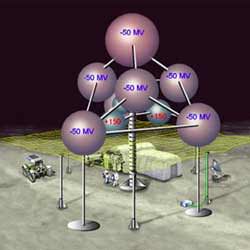

Artist illustration of an electromagnetic shield that could protect astronauts. Image credit: Hubble. Click to enlarge.

Opposite charges attract. Like charges repel. It’s the first lesson of electromagnetism and, someday, it could save the lives of astronauts.

NASA’s Vision for Space Exploration calls for a return to the Moon as preparation for even longer journeys to Mars and beyond. But there’s a potential showstopper: radiation.

Space beyond low-Earth orbit is awash with intense radiation from the Sun and from deep galactic sources such as supernovas. Astronauts en route to the Moon and Mars are going to be exposed to this radiation, increasing their risk of getting cancer and other maladies. Finding a good shield is important.

The most common way to deal with radiation is simply to physically block it, as the thick concrete around a nuclear reactor does. But making spaceships from concrete is not an option. (Interestingly, it might be possible to build a moonbase from a concrete mixture of moondust and water, if water can be found on the Moon, but that’s another story.) NASA scientists are investigating many radiation-blocking materials such as aluminum, advanced plastics and liquid hydrogen. Each has its own advantages and disadvantages.

Those are all physical solutions. There is another possibility, one with no physical substance but plenty of shielding power: a force field.

Most of the dangerous radiation in space consists of electrically charged particles: high-speed electrons and protons from the Sun, and massive, positively charged atomic nuclei from distant supernovas.

Like charges repel. So why not protect astronauts by surrounding them with a powerful electric field that has the same charge as the incoming radiation, thus deflecting the radiation away?

Many experts are skeptical that electric fields can be made to protect astronauts. But Charles Buhler and John Lane, both scientists with ASRC Aerospace Corporation at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, believe it can be done. They’ve received support from the NASA Institute for Advanced Concepts, whose job is to fund studies of far-out ideas, to investigate the possibility of electric shields for lunar bases.

“Using electric fields to repel radiation was one of the first ideas back in the 1950s, when scientists started to look at the problem of protecting astronauts from radiation,” Buhler says. “They quickly dropped the idea, though, because it seemed like the high voltages needed and the awkward designs that they thought would be necessary (for example, putting the astronauts inside two concentric metal spheres) would make such an electric shield impractical.”

Buhler and Lane’s approach is different. In their concept, a lunar base would have a half dozen or so inflatable, conductive spheres about 5 meters across mounted above the base. The spheres would then be charged up to a very high static-electrical potential: 100 megavolts or more. This voltage is very large but because there would be very little current flowing (the charge would sit statically on the spheres), not much power would be needed to maintain the charge.

The spheres would be made of a thin, strong fabric (such as Vectran, which was used for the landing balloons that cushioned the impact for the Mars Exploration Rovers) and coated with a very thin layer of a conductor such as gold. The fabric spheres could be folded up for transport and then inflated by simply loading them with an electric charge; the like charges of the electrons in the gold layer repel each other and force the sphere to expand outward.

Placing the spheres far overhead would reduce the danger of astronauts touching them. By carefully choosing the arrangement of the spheres, scientists can maximize their effectiveness at repelling radiation while minimizing their impact on astronauts and equipment at the ground. In some designs, in fact, the net electric field at ground level is zero, thus alleviating any potential health risks from these strong electric fields.

Buhler and Lane are still searching for the best arrangement: Part of the challenge is that radiation comes as both positively and negatively charged particles. The spheres must be arranged so that the electric field is, say, negative far above the base (to repel negative particles) and positive closer to the ground (to repel the positive particles). “We’ve already simulated three geometries that might work,” says Buhler.

Portable designs might even be mounted onto “moon buggy” lunar rovers to offer protection for astronauts as they explore the surface, Buhler imagines.

It sounds wonderful, but there are many scientific and engineering problems yet to be solved. For example, skeptics note that an electrostatic shield on the Moon is susceptible to being short circuited by floating moondust, which is itself charged by solar ultraviolet radiation. Solar wind blowing across the shield can cause problems, too. Electrons and protons in the wind could become trapped by the maze of forces that make up the shield, leading to strong and unintended electrical currents right above the heads of the astronauts.

The research is still preliminary, Buhler stresses. Moondust, solar wind and other problems are still being investigated. It may be that a different kind of shield would work better, for instance, a superconducting magnetic field. These wild ideas have yet to sort themselves out.

But, who knows, perhaps one day astronauts on the Moon and Mars will work safely, protected by a simple principle of electromagnetism even a child can understand.

Original Source: Science@NASA