Image credit: NASA

More than 100 planetary systems have already been discovered around distant stars. Unfortunately, the limitations of current technology mean that only giant planets (like Jupiter) have so far been detected, and smaller, rocky planets similar to Earth remain out of sight.

How many of the known exoplanetary systems might contain habitable Earth-type planets? Perhaps half of them, according to a team from the Open University, led by Professor Barrie Jones, who will be describing their results today at the RAS National Astronomy Meeting in Milton Keynes.

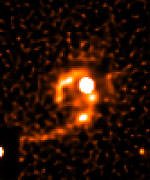

By using computer modelling of the known exoplanetary systems, the group has been able to calculate the likelihood of any ‘Earths’ existing in the so-called habitable zone – the range of distances from each central star where life as we know it could survive. Popularly known as the “Goldilocks” zone, this region would be neither too hot for liquid water, nor too cold.

By launching ‘Earths’ (with masses between 0.1 and 10 times that of our Earth) into a variety of orbits in the habitable zone and following their progress with the computer model, the small planets have been found to suffer a variety of fates. In some systems the proximity of one or more Jupiter-like planets results in gravitational ejection of the ‘Earth’ from anywhere in the habitable zone. However, in other cases there are safe havens in parts of the habitable zone, and in the remainder the entire zone is a safe haven.

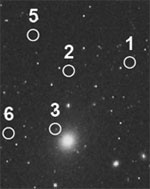

Nine of the known exoplanetary systems have been investigated in detail using this technique, enabling the team to derive the basic rules that determine the habitability of the remaining ninety or so systems.

The analysis shows that about half of the known exoplanetary systems could have an ‘Earth’ which is currently orbiting in at least part of the habitable zone, and which has been in this zone for at least one billion years. This period of time has been selected since it is thought to be the minimum required for life to arise and establish itself.

Furthermore, the models show that life could develop at some time in about two thirds of the systems, since the habitable zone moves outwards as the central star ages and becomes more active.

Habitable Moons

A different aspect of this problem is being studied by PhD student David Underwood, who is investigating the possibility that Earth-sized moons orbiting giant planets could support life. A poster setting out the possibilities will be presented during the RAS National Astronomy Meeting.

All of the planets discovered so far are of similar mass to Jupiter, the largest planet in our Solar System. Just as Jupiter has four planet-sized moons, so giant planets around other stars may also have extensive satellite systems, possibly with moons similar in size and mass to Earth.

Life as we know it cannot evolve on a gaseous, giant planet. However, it could survive on Earth-sized satellites orbiting such a planet if the giant is located in the habitable zone.

In order to determine which of the gas giants located within habitable zones could possess a life-friendly moon, the computer models search for systems where the orbits of Earth-sized satellites would be stable and confined within the habitable zone for at least the one billion years needed for life to emerge.

The OU team’s method of determining whether any putative ‘Earths’ or Earth-sized satellites in habitable zones can offer suitable conditions for life to evolve can be applied rapidly to any planetary systems that are newly announced. Future searches for ‘Earths’ and extraterrestrial life should also be assisted by identifying in advance the systems most likely to house habitable worlds.

The predictions made by the simulations will have a practical value in years to come when next-generation instruments will be able to search for the atmospheric signatures of life, such as large amounts of oxygen, on ‘Earths’ and Earth-sized satellites.

Background

There are currently 105 known planetary systems other than our own, with 120 Jupiter-like planets orbiting them. Two of these systems contain three known planets, 11 contain two and the remaining 92 each have one. All but one of these planets has been discovered by their effect on their parent stars’ motion in the sky, causing them to wobble regularly. The extent of these wobbles can be determined from information within the light received from the stars. The remaining planet was discovered as the result of a slight dimming of starlight caused by its regular passage across the disk of its parent star.

Future discoveries are likely to contain a higher proportion of systems that resemble our Solar System, where the giant planets orbit at a safe distance beyond the habitable zone. The proportion of systems that could have habitable ‘Earths’ is, therefore, likely to rise. By the middle of the next decade, space telescopes should be capable of seeing any ‘Earths’ and investigating them to see if they are habitable, and, indeed, whether they actually support life.

Original Source: RAS News Release