Michael Benson, author of Beyond: Visions of the Interplanetary Probes (read Universe Today’s review) took some time from his busy schedule, and nasty cold, to answer some of our questions about his book and interest in astronomy and space exploration. Benson was interviewed by Mark Mortimer.

Universe Today: You say this book is the cumulation of sifting through tens of thousands of image files on computers. What was your selection criteria for the few that made it into the book?

Michael Benson: Well, to start off with, the jaw-drop factor, of course. Stuff that was incredible, I tried my best to get in. After that, though, of course you have the inevitable limitations of the book medium, with its fixed number of pages, plus then I had to divide the solar system up into chapters and try to give each one at least its due if not more, pretty soon I realized I had to winnow the available images down to not as many as I would have liked. And then there was the color versus B&W question — I wanted to get in as many good color shots as I could, though I have a real weakness for black and white photography. Essentially, though, whatever really made me gaze in amazement got in. I have to say, though, that I have a lot of really first-rate processed pictures on my hard drive that I’d love to use elsewhere sometime. Some of it has never been seen before, except for by a small cadre of planetary scientists, and then usually in black and white.

UT: As an artist did you feel like an outsider when discussing these images or did you feel like a member of the group of technicians?

MB: Neither. I always approached them as an aesthetic challenge — how to get them to “pop” — to reveal that they weren’t shot through a digitized grid but through optically pure glass, as it were. And much of the work behind getting them to the right place was technical — using photoshop or other programs — but this is also the tool of a photographer, or ‘artist’ if you will. And even when working with Dr. Paul Geissler, who is an eminent planetary scientist and remote imaging expert, I didn’t feel like an outsider — we had a good collaboration — nor like I belonged to some group of techies either. (I don’t think he feels like the latter either, come to think of it, though he recently took a job at the US Geological Survey — which makes highly accurate maps of all the planets based on space imaging! Which is about as technical as it gets.)

UT: How would you compare the artistic qualities and values of colour to black and white in this medium?

MB: I like both for different reasons. It also depends on the planetary body being represented, to an extent. Black and white pictures of Jupiter’s implacably volcanic, sulphurously yellow-orange moon Io, for example, practically don’t make any sense in a book of this type. They make perfect sense when it comes to conducting science, but would’ve been a bit hard to justify having them in my book, given that Io is by far the most lurid object in the Solar System. And by the same token Europa, Io’s closest neighboring moon, which is a spherical iceberg of fissured, chaotic ice, doesn’t really need to be in color — though it also looks awesome in color. But you get the essence of its story in black and white, if I can put it that way. (Though part of that essence is in fact its mystery — what’s going on under that global ice-cap?)

UT: Do you have a favourite/most photogenic planet? For example Venus seems to be heavily weighed in the book.

MB: Actually, Venus gets fewer pages than either Mars or Jupiter. Jupiter may be the most complex and compelling, though Saturn is a close second, because of its perfect rings. Saturn could scarcely be _more_ photogenic — we’re very lucky to have it in the solar system, because it shows what cosmic perfection really is. And as for Jupiter, as I said in my book, it’s a solar system in miniature — it’s endlessly fascinating and kinetic. The last quality is hard to show with stills, but not impossible.

UT: How were you able to convince a publisher to go for a book of images freely available on the web?

MB: Many of the images were available in raw form at specialized planetary science sites, not “freely available,” in the sense that they required substantial processing and mosacking, rendering into color or what have you. Plus even the images that are more readily available — for example, at NASA’s outreach site A Planetary Photojournal — still required substantial processing, most of them, to get them to work at the resolution quality we have available on the page, as opposed to the screen, where lower resolutions still work.

But the premise of the question is a bit flawed. Publishers are delighted if they can base a book on public domain images, because then they don’t have to pay for it!

UT: Considering the forward, do you think a living carbon based life form will explore our solar system? Other star systems? Do you think humans will do this?

MB: I do. We suffer a bit of temporal tunnel vision as a species. Even if we don’t do it for a hundred or two hundred years in the case of the solar system — and much later for the stars — I still think we’ll do it. Our current hesitation about it has to do with the sluggish pace of crewed exploration after Apollo and also the sense that the environments are so hostile that it might not be desirable to do it. But technology will march onwards and make these such things easier. And then, as soon as it is possible for tourists to actually go to, for example, Jupiter, there will be a huge rush to go there. Or Mars, of course. Or the Moon…

UT: Considering the afterward, where do you think people fit into the universal schema of things?

MB: Oh, I tend to agree with Ren — Lawrence Weschler — that for now at least we seem to be the only creatures that can experience that sense of awe that is ultimately one of the roots of our sentience. My discussion with him had to do with whether machines could ever experience this. I believe one day they will, he’s not so sure. Wasn’t it Asimov who, when asked if he really believed machines would one day think, said “well, I’m a machine, and I think”?

But in the end I think Ren’s daughter Sara is right in saying that the universe in a sense needs us, because we are capable of appreciating its beauty. Another way of putting it, I suppose, is that we are one of the ways in which the universe can appreciate its own splendor. And of course we are pieces of work ourselves, just to coin a phrase!

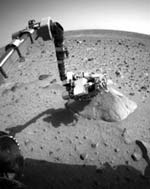

UT: No 3D images are in the book though we are presently getting some from Mars. What is your opinion of the artistic value of 3D images for this subject and media?

MB: Well, as someone who has barely pried my 3-D glasses of my nose for the last couple weeks, as I peer in fascination at the images from the Spirit and Opportunity rovers, I don’t know how objective I can be on the question. I really like it — though more for that “you are there” sensation than for aesthetic reasons I suppose. But there is no reason why 3-D images can’t be savored for their aesthetic qualities as well. I’ll be able to answer with more conviction on the question after this whole rover experiment is over, because there will really be many thousands of 3-D pictures to go through by then, and no doubt some of them will work on the multiple levels required to be considered art. So the jury — not that I consider myself a jury — is out on the question, but not for too long. Personally, I’d love to see a purple-orange cactus appear on the lip of a crater one of these days — though the artistic qualities of the shot will be the last thing on anyone’s mind if that happens!