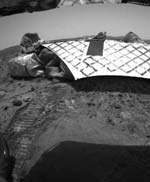

Image credit: NASA/JPL

If the next Mars Exploration Rover, Opportunity, is as successful as Spirit, then engineers might loosen up a bit and send rovers to more dangerous locations on Mars. Selecting landing sites on Mars is a difficult job; you need to balance the scientific payoff with the chance of losing the rover when it first arrives at Mars. If the terrain is too rocky, the rover could be destroyed before the mission even begins. One possible target for a future mission is near a volcano called Apollinaris Patera, which could have kept water liquid – a potential home for life.

The anticipated Mars landing on Jan. 24 of the Opportunity rover will be a bit more challenging than the Spirit’s bounce onto the red planet earlier this month, according to a University at Buffalo geologist, but if it’s successful, then scientists will be able to be much bolder about selecting future Mars landing sites.

“If both of these landers survive with airbag technology, then it blows the doors wide open for future Mars landing sites with far more interesting terrain,” said Tracy Gregg, Ph.D., University at Buffalo assistant professor of geology in the UB College of Arts and Sciences and a planetary volcanologist.

Gregg, who headed a national conference at UB in 1999 regarding the selection of future Mars landing sites, is chair of the geologic mapping standards committee of the NASA Planetary Cartography Working Group.

“With the success of Spirit, I feel so much more confident about future Mars landers,” said Gregg. “The airbags seem to be able to withstand quite a bit of trauma.”

Gregg remembers attending a conference presentation a few years ago by Matt P. Golombek, Ph.D., planetary geologist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and, at the time, the principal investigator on the Mars Pathfinder mission, in which he proposed the airbag landing technology.

“He listed the 15 steps that had to happen at exactly the right time and in exactly the right way in order for this technology to work. The general mood in the lecture hall was, ‘Yeah, right, good luck,'” Gregg remembered. “Well, the next year, he got up to a standing-room-only crowd at a meeting of the same organization and he described all of the same steps that the Pathfinder had successfully completed on Mars. He got a standing ovation.”

The selection of Mars landing sites is a complex balancing act, Gregg says, where the potential for important scientific discoveries has to be balanced against the requirement that sites be absolutely safe so that the rovers can perform well and send data back to earth.

Both Gusev Crater, where the Spirit landed, and Sinus Meridiani, where Opportunity is scheduled to land, were chosen, Gregg says, because they are not expected to have large boulders, steep cliffs or deep craters that could pop an airbag or swallow up the lander preventing the transmission of radio signals.

“If Opportunity survives the landing on Jan. 24, there is a high possibility that we will get to see layers of ancient rock, deposited when Mars was warm and wet and could have supported life,” she says. “Evidence of river channels, which we expect to see at Sinus Meridiani, could be remnants of that early, warm history.”

When pictures start coming back from Opportunity, Gregg will have her eyes peeled, searching for layers in the walls of the dried-up river channels.

“Those layers could be lava flows,” explained Gregg, noting that often the best place to look for evidence of life on any planet is near volcanoes.

“That may sound counterintuitive, but think about Yellowstone National Park, which really is nothing but a huge volcano,” she says. “Even when the weather in Wyoming is 20 below zero, all the geysers, which are fed by volcanic heat, are swarming with bacteria and all kinds of happy little things cruising around in the water.

“So, since we think that the necessary ingredients for life on earth were water and heat, we are looking for the same things on Mars, and while we definitely have evidence of water there, we still are looking for a source of heat.”

Gregg hopes that a future landing Mars site will be near a volcano, particularly one called Apollinaris Patera.

“A landing site near a volcano might be possible, now that the airbag technology has worked so wonderfully,” she says.

Original Source: University of Buffalo News Release