2003 was quite a year for space and astronomy, with the loss of Columbia and Chinese making their first successful human space launch. It was definitely a year of highs and lows. Join Universe Today as we look at the top space stories of the year. In no particular order…

Columbia Disaster

Space exploration is an extremely dangerous business. This lesson was hammered home in 2003 when the space shuttle Columbia broke up above Texas as it was on approach to land in Florida. The lives of seven astronauts were lost in a few firey moments on February 1, 2003. Months of investigation revealed that a chunk of foam fell off the external fuel tank and smashed a hole in the shuttle’s carbon-fibre wing panels. When Columbia was returning to Earth at the end of its mission, the open hole in the wing allowed hot gasses to penetrate the shuttle’s heat protection. The Columbia Accident Investigation board placed the blame on the foam, but said that NASA’s lack of safety allowed the accident to happen in the first place. While NASA is implementing the safety recommendations to get the shuttles flying again, the US administration is said to be planning a bold new program in space.

Columbia Accident Investigation website

http://www.caib.us

Chinese Space Launch

Previously unknown, astronaut Yang Liwei became an instant celebrity on October 15, when he became the first human the Chinese space program sent into space. Liwei was launched from the Jiuquan desert launch site and orbited the Earth only 14 times in 21 hours. Only the United States and Russia have ever been capable of sending humans into space before this year. Riding high on their accomplishments, the normally tight-lipped Chinese revealed more details of their space program this year: additional human launches, a space station, probes to the Moon, and eventually humans on the Moon. NASA was one of the first to congratulate the Chinese on their accomplishment, but some space industry experts believe that this will spur the agency on to a new spirit of competition.

SpaceShipOne Goes Supersonic

The space community was expecting US President George Bush to make some announcement about the future of US space exploration on December 17, the 100th anniversary of the first Wright Brothers flight. He didn’t, but on that day Scaled Composites – an aircraft manufacturer in California – made news with the first rocket test flight of SpaceShipOne; their suborbital rocket plane. The unique-looking aircraft was carried to an altitude of 14,600 metres by the White Knight carrier plane and then released. It fired its hybrid rocket engine and blasted up to an altitude of 20,700 metres; breaking the sound barrier as it went. SpaceShipOne is considered the top contender to win the $10 million X-Prize which will be awarded to the first privately-built suborbital spacecraft which can fly to 100 km.

Scaled Composites website

http://www.scaled.com

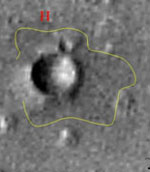

Disappearance of Beagle 2

In a perfect world, this would be a tribute to the successful landing of Beagle 2; Britain’s $50 million, 70-kg Mars lander which traveled to the Red Planet on board the European Space Agency’s Mars Express spacecraft. Unfortunately, it looks like Mars has swallowed yet another spacecraft, and at the time of this writing the lander has failed to communicate home; either through Mars Odyssey orbiting above, or Earth-based radio observatories. Beagle 2 was supposed to land in the relatively safe Isidis Planitia region of Mars and then search for evidence of microbial life for 180-days with a suite of sensitive instruments. The best opportunity to communicate with Beagle 2 comes in 2004, though, when Mars Express reaches its final orbit and will attempt to make contact. Maybe the recovery of Beagle 2 will make one of the top stories in 2004.

Beagle 2 website

http://www.beagle2.com

Mars’ Closest Approach to the Earth

Mars took centre stage this summer when it made its closest approach to the Earth in over 60,000 years. Because of their orbits, the Earth and Mars get close every two years, but on August 27 they were only 55,758,000 kilometres apart. The mainstream media picked up the story, and for a while it was Mars mania. Astronomy clubs and planetariums that held special Mars observing nights for the public were totally overwhelmed by the number of people who showed up to have a peek through a telescope. And they weren’t disappointed. Even with a relatively small 6″ telescope and good observing conditions, it was possible to see details on Mars like its polar caps, dust storms, and darker patches. If you missed it this year, don’t worry, Mars will be even closer in 2287.

Biggest Solar Flare Ever Observed

Our Sun showed a nasty side this year, with a series of powerful flares and coronal mass ejections. On November 4, 2003, the Sun surprised even the most experienced solar astronomers with the most powerful flare anyone had ever seen. It was so powerful that it momentarily blinded cameras designed to measure flares, so it actually took a few days for astronomers to calculate just how bright it was. In the end, it was categorized as an X28 flare. But this was just one of a series of powerful flares, many of which were aimed directly at our Earth, sending wave after wave of material our direction. Incredibly, there were very few problems on the Earth – contact was lost with a Japanese satellite, and some communications were disrupted – but we got through it largely unharmed. The auroras, however, were awesome.

SOHO website

http://sohowww.nascom.nasa.gov

Farewell Galileo

On September 20, 2003, NASA’s Galileo spacecraft finally ended its 14-year journey to the Jovian system with its triumphant crash into the giant gas planet. Galileo was plagued with problems right from the start, including a series of launch delays, and a failure of its main antenna. But NASA engineers were able to overcome these obstacles, and use the spacecraft to make some incredible discoveries about the Jupiter and its moons. Photos taken by the Galileo gave scientists proof that three of the moons might have liquid water under their icy surfaces. Passing through Jupiter’s massive radiation took its toll on the spacecraft, and various instruments started to fail, including its main camera, which went offline in 2002. With the spacecraft failing, controllers decided it would be best to crash Galileo into Jupiter, to protect potential life on the Jovian moons from contamination.

Galileo website

http://www2.jpl.nasa.gov/galileo

Age of the Universe

This is the year we learned how old we are – well… how old the Universe is. Thanks to a comprehensive survey of the sky performed by NASA’s Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP), astronomers were able to calculate that the Universe is 13.7 billion years old, give or take 200 million years. WMAP, launched in June 2001, measured the sky’s cosmic background radiation, which was unleashed 380,000 years after the Big Bang – when the expanding Universe had cooled down enough for the first atoms to form. This wasn’t the first survey of the cosmic background radiation, but the WMAP is so sensitive, it was able to detect extremely slight temperature changes in the radiation.

Wilkinson Microwave Anistropy Probe website

http://map.gsfc.nasa.gov

Spitzer Space Telescope

The last of great observatories, the Spitzer Space Telescope (previously named SIRTF) was finally launched into space on August 25, 2003. Almost every object in the Universe radiates heat in the infrared spectrum, which Spitzer is designed to detect. So objects which might be hidden to visible light telescopes, like Hubble, can be seen in tremendous detail with Spitzer. The observatory completed its 60-day on-orbit checkout period and calibration, and just before the end of the year the operators released four incredible photographs that demonstrated the potential of this instrument. Spitzer will help astronomers look at the dusty hearts of galaxies, young planetary discs, and cool objects like comets, and brown dwarfs. Spitzer may even help astronomers understand the nature of dark matter.

Spitzer Space Telescope website

http://www.spitzer.caltech.edu

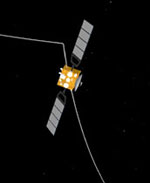

Mars Express Arrives

The search for the missing Beagle 2 lander overshadowed the success of the European Space Agency’s Mars Express spacecraft, which went into a perfect orbit on December 25, and then performed additional maneuvers flawlessly. This is the Europe’s first mission to the Red Planet, and it’s got an important job to do. In addition to helping out the search for Beagle 2, Mars Express will begin mapping the surface of Mars with a powerful radar system which should reveal underground deposits of water and ice.

Mars Express website

http://www.esa.int/SPECIALS/Mars_Express