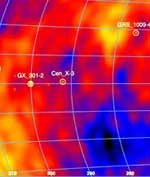

Image credit: Fermilab

Astronomers don’t know what Dark Matter is, but they can see the effect of its gravity on regular matter. One possibility is that it’s regular matter, but isn’t emitting enough light for us to see. Another idea is that Dark Matter is an exotic form of matter that’s much more massive than regular particles, but interact so weakly that they’re almost impossible to detect. Researchers with the Cryogenic Dark Matter Search II have set up a series of detectors in an old iron mine in Minnesota that’s shielded from cosmic radiation and might sense these particles.

Using detectors chilled to near absolute zero, from a vantage point half a mile below ground, physicists of the Cryogenic Dark Matter Search today (November 12) announced the launch of a quest that could lead to solving two mysteries that may turn out to be one and the same: the identity of the dark matter that pervades the universe, and the existence of supersymmetric particles predicted by particle physics theory. Scientists of CDMS II, an experiment managed by the Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory hope to discover WIMPs, or weakly interacting massive particles, the leading candidates for the constituents of dark matter-which may be identical to neutralinos, undiscovered particles predicted by the theory of supersymmetry.

“There’s this arrow from particle physics and this arrow from cosmology and they seem to be pointing to the same place,” said Case Western Reserve University’s Dan Akerib, deputy project manager of CDMS II. “Detection of a neutralino would be very big for cosmology and it would also be very big for particle physics.”

The CDMS II experiment, a collaboration of scientists from 12 institutions with support from DOE’s Office of Science and the National Science Foundation, uses a detector located deep underground in the historic Soudan Iron Mine in northeastern Minnesota. Experimenters seek signals of WIMPs, particles much more massive than a proton but interacting so weakly with other particles that thousands would pass through a human body each second without leaving a trace.

Remarkably, in the kind of convergence that gets physicists’ attention, the characteristics of this cosmic missing matter particle now appear to match those of the supersymmetric neutralino.

“Either that is a cosmic coincidence, or the universe is telling us something,” said Fermilab’s Dan Bauer, CDMS project manager.

By watching how galaxies spin-how gravity affects their contingent stars-astronomers have known for 70 years that the matter we see cannot constitute all the matter in the universe. If it did, galaxies would fly apart. Recent calculations indicate that ordinary matter containing atoms makes up only 4 percent of the energy-matter content of the universe. “Dark energy” makes up 73 percent, and an unknown form of dark matter makes up the last 23 percent.

“It is often said that this is the ultimate Copernican Revolution,” said David Caldwell, a physicist at the University of California at Santa Barbara and chair of the CDMS Executive Committee. “Not only are we not at the center of the universe, but we are not even made of the same stuff as most of the universe.”

Measurements of the cosmic microwave background, residual radiation left over from the Big Bang, have recently placed severe constraints on the nature and amount of dark matter. The lightweight neutrino can account for only a few percent of the missing mass. If neutrinos constituted the main component of dark matter, they would act on the cosmic microwave background of the universe in ways that the recent Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe should have observed-but did not.

Meanwhile, particle physicists have kept a lookout for particles that will extend the Standard Model, the theory of fundamental particles and forces. Supersymmetry, a theory that takes a big step toward the unification of all of the forces of nature, predicts that every matter particle has a massive supersymmetric counterpart. No one has yet seen one of these “superpartners.” Theory specifies the neutralino as the lightest neutral superpartner, and the most stable, a necessary attribute for dark matter. The neutralino’s predicted abundance and rate of interaction also make it a likely dark matter candidate, and Caldwell noted the impact that CDMS II could have.

“Discovery,” he said, “would be a great breakthrough, one of the most important of the century.”

Only occasionally would a WIMP hit the nucleus of a terrestrial atom, and the constant background “noise” from more mundane particle events-such as the common cosmic rays constantly showering the earth-would normally drown out these rare interactions. Placing the CDMS II detector beneath 740 meters of earth screens out most particle noise from cosmic rays. Chilling the detector to 50 thousandths of a degree above absolute zero reduces background thermal energy to allow detection of individual particle collisions. Fermilab’s Bauer estimates that with sufficiently low backgrounds, CDMS needs only a few interactions to make a strong claim for detection of WIMPs.

“The powerful technology we deploy allows an unambiguous identification of events in the crystals caused by any new form of matter,” said CDMS cospokesperson Bernard Sadoulet of the University of California at Berkeley.

Cospokesperson Blas Cabrera of Stanford University concurred.

“We believe we have the best apparatus in the world in terms of being able to identify WIMPs,” Cabrera said.

“This endeavor is a good example of cooperation between the DOE’s Office of High Energy Physics and the National Science Foundation in helping scientists address the origin of the dark matter in the universe,” said Raymond Orbach, Director of the Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

“CDMS II is the kind of innovative and pathbreaking research NSF is proud to support,” said Michael Turner, Assistant Director for Math and Physical Sciences at the National Science Foundation. “If it detects a signal it may tell us what the dark matter is and give us an important clue as to how gravity fits together with the other forces. This type of experiment shows how the universe can be used as a laboratory for getting at the some of the most basic questions we can ask as well as how DOE and NSF are working together.”

While CDMS II watches for WIMPs, scientists at Fermilab’s Tevatron particle accelerator will try to create neutralinos by smashing protons and antiprotons together.

“CDMS can tell us the mass and interaction rate of the WIMP,” said collaborator Roger Dixon of Fermilab. “But it will take an accelerator to tell us whether it’s a neutralino.”

CDMS II collaborators include Brown University, Case Western Reserve University, Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, Lawrence Berkeley National Accelerator Laboratory, National Institute of Standards and Technology, Princeton University, Santa Clara University, Stanford University, University of California at Berkeley, University of California at Santa Barbara, University of Colorado at Denver, University of Minnesota.

Funding for the CDMS II experiment comes from the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy and the Astronomy and Physics Division of the National Science Foundation.

Fermilab is a national laboratory funded by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy and operated by Universities Research Association, Inc.

Original Source: Fermilab News Release