Image credit: Cornell University

At the South Pole of the Moon, there is a region that is always in the shadow of craters which scientists have long believed could have deposits of water ice. Despite the fact that ice was detected by two spacecraft that orbited the moon, a new survey of the area by the giant Arecibo radio observatory has failed to find any surface deposits of ice. This doesn’t mean that the ice isn’t there, but it might be trapped in a large area under the surface, like lunar permafrost. Arecibo is a good instrument for detecting ice because it gives a very specific echo signature in the radio spectrum.

Despite evidence from two space probes in the 1990s, radar astronomers say they can find no signs of thick ice at the moon’s poles. If there is water at the lunar poles, the researchers say, it is widely scattered and permanently frozen inside the dust layers, something akin to terrestrial permafrost.

Using the 70-centimeter (cm)-wavelength radar system at the National Science Foundation’s (NSF) Arecibo Observatory, Puerto Rico, the research group sent signals deeper into the lunar polar surface — more than five meters (about 5.5 yards) — than ever before at this spatial resolution. “If there is ice at the poles, the only way left to test it is to go there directly and melt a small volume around the dust and look for water with a mass spectrometer,” says Bruce Campbell of the Center for Earth and Planetary Studies at the Smithsonian Institution.

Campbell is the lead author of an article, “Long-Wavelength Radar Probing of the Lunar Poles,” in the Nov. 13, 2003, issue of the journal Nature . His collaborators on the latest radar probe of the moon were Donald Campbell, professor of astronomy at Cornell University; J.F. Chandler of Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory; and Alice Hine, Mike Nolan and Phil Perillat of the Arecibo Observatory, which is managed by the National Astronomy and Ionosphere Center at Cornell for the NSF.

Suggestions of lunar ice first came in 1996 when radio data from the Clementine spacecraft gave some indications of the presence of ice on the wall of a crater at the moon’s south pole. Then, neutron spectrometer data from the Lunar Prospector spacecraft, launched in 1998, indicated the presence of hydrogen, and by inference, water, at a depth of about a meter at the lunar poles. But radar probes by the 12-cm-wavelength radar at Arecibo showed no evidence of thick ice at depths of up to a meter. “Lunar Prospector had found significant concentrations of hydrogen at the lunar poles equivalent to water ice at concentrations of a few percent of the lunar soil,” says Donald Campbell. “There have been suggestions that it may be in the form of thick deposits of ice at some depth, but this new data from Arecibo makes that unlikely.”

Says Bruce Campbell, “There are no places that we have looked at with any of these wavelengths where you see that kind of signature.”

The Nature paper notes that if ice does exist at the lunar poles it would be considerably different from “the thick, coherent layers of ice observed in shadowed craters on Mercury,” found in Arecibo radar imaging. “On Mercury what you see are quite thick deposits on the order of a meter or more buried by, at most, a shallow layer of dust. That’s the scenario we were trying to nail down for the moon,” says Bruce Campbell. The difference between Mercury and the moon, the researchers say, could be due to the lower average rate of comets striking the lunar surface, to recent comet impacts on Mercury or to a more rapid loss of ice on the moon.

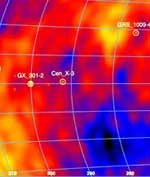

What makes the lunar poles good cold traps for water is a temperature of minus 173 degrees Celsius (minus 280 degrees Fahrenheit). The limb of the sun rises only about two degrees above the horizon at the lunar poles so that sunlight never penetrates into deep craters, and a person standing on the crater floor would never see the sun. The Arecibo radar probed the floors of two craters in permanent shadow at the lunar south pole, Shoemaker and Faustini, and, at the north pole, the floors of Hermite and several small craters within the large crater Peary. In contrast, Clementine focused on the sloping walls of Shackleton crater, whose floor can’t be “seen” from Earth. “There is a debate on how to interpret data from a rough, tilted surface,” says Bruce Campbell.

The Arecibo radar probe is a particularly good detector of thick ice because it takes advantage of a phenomenon known as “coherent backscatter.” Radar waves can travel long distances without being absorbed in ice at temperatures well below freezing. Reflections from irregularities inside the ice produce a very strong radar echo. In contrast, lunar soil is much more absorptive and does not give as strong a radar echo.

Original Source: Cornell News Release