Image credit: NASA

Berto Monard, an amateur astronomer from South Africa was lucky enough to spot the afterglow from a powerful gamma-ray burst – beating professional astronomers to the target. The 40-second-long burst was discovered by NASA’s HETE spacecraft, which provided Monard rough coordinates of where to look. He was able to provide the astronomy community with a precise location so they can follow up days or weeks later to try and determine what actually caused the explosion.

Armed with a 12-inch telescope, a computer, and a NASA email alert, Berto Monard of South Africa has become the first amateur astronomer to discover an afterglow of a gamma-ray burst, the most powerful explosion known in the Universe.

The discovery highlights the ease in tapping into NASA’s burst alert system, as well as the increasing importance that astronomy enthusiasts play in helping scientists understand fleeting and random events, such as star explosions and gamma-ray bursts.

This 40-second-long burst was detected by NASA’s High-Energy Transient Explorer (HETE) on July 25. Monard’s positioning of the lingering afterglow, and thus burst location, has given way to precision follow-up study, an opportunity that very well might have been missed: At the time of the burst, thousands of professional astronomers were attending the International Astronomical Union conference in Sydney, Australia, far away from their observatories.

“I have seen a multitude of stars and galaxies and even supernovae, but this gamma-ray burst afterglow is among the most ancient light that has ever graced my telescope,” Monard said. “The explosion that caused this likely occurred billions of years ago, before the Earth was formed.”

Gamma-ray bursts, many of which now appear to be massive star explosions billions of light years away, only last for a few milliseconds to upwards of a minute. Prompt identification of an afterglow, which can last for hours to days in lower-energy light such as X ray and optical, is crucial for piecing together the explosion that caused the burst.

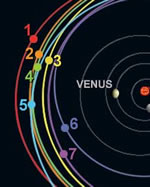

Monard notified the pros of the burst location within seven hours of the HETE detection. The Interplanetary Network (IPN), comprising six orbiting gamma-ray detectors, confirmed the location shortly thereafter.

Because of the nature of gamma-ray light, which cannot be focused like optical light, HETE locates bursts to only within a few arcminutes. (An arcminute is about the size of an eye of a needle held at arm’s length.) Most gamma-ray bursts are exceedingly far, so myriad stars and galaxies fill that tiny circle. Without prompt localization of a bright and fading afterglow, scientists have great difficulty locating the gamma-ray burst

location days or weeks later.

The study of gamma-ray bursts (and increasing ease of amateur participation) comes through two innovations: faster burst detectors like HETE and a near-instant information relay system called the Gamma-ray Burst Coordinates Network, or GCN, which is located at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md.

The typical pattern follows: HETE detects a burst and, within a few seconds to about a minute, relays a location to the GCN. Instantly, the automated GCN notifies scientists and amateur astronomers worldwide about the burst event via email, pagers, and a Web site.

Monard is a member of the American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO). This organization operates the AAVSO International High Energy Network, which acts as a liaison between the amateur and the professional communities. Monard essentially used GCN information passed through the AAVSO and other network groups and turned his telescope to the location determined by HETE.

“In the past two years, HETE has opened the door wide for rapid follow-up studies by professional astronomers,” said HETE Principal Investigator George Ricker of MIT. “Now, with GRB030725, the worldwide community of dedicated and expert amateur astronomers coordinated through the AAVSO is leaping through that door to join the fun.”

Monard, a Belgian national living in South Africa, has other discoveries under his belt, including ten supernovae and several outbursts from neutron star systems, as part of his participation with the worldwide Center for Backyard Astrophysics network and the Variable Star Network.

The AAVSO, founded in 1911, is a non-profit, scientific organization with members in 46 countries. It coordinates, compiles, digitizes and disseminates observations on stars that change in brightness (variable stars) to researchers and educators worldwide. Its International High Energy Network was created with cooperation from NASA.

HETE was built by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology under NASA’s Explorer Program. HETE is a collaboration among NASA, MIT, Los Alamos National Laboratory; France’s Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales, Centre d’Etude Spatiale des Rayonnements, and Ecole Nationale Superieure de l’Aeronautique et de l’Espace; and Japan’s Institute of Physical and Chemical Research (RIKEN). The science team includes members from the University of California (Berkeley and Santa Cruz) and the University of Chicago, as well as from Brazil, India and Italy.