Image credit: NASA/JPL

It turns out that Mars has been hiding its water underneath a layer of dry ice. By tracking the seasonal changes at Mars northern ice cap, NASA’s Mars Odyssey spacecraft has watched how a layer of carbon dioxide permafrost comes and goes. When the permafrost dissipates in the Spring, Mars reveals a soil layer mixed with large amounts of water ice. In some places, the water ice content is more than 90% by volume. During the winter, the dry ice permafrost can reach more than a metre in thickness.

NASA’s Mars Odyssey spacecraft is revealing new details about the intriguing and dynamic character of the frozen layers now known to dominate the high northern latitudes of Mars. The implications have a bearing on science strategies for future missions in the search of habitats.

Odyssey’s neutron and gamma-ray sensors have tracked seasonal changes as layers of “dry ice” (carbon-dioxide frost or snow) accumulate during northern Mars’ winter and then dissipate in the spring, exposing a soil layer rich in water ice– the martian counterpart to permafrost.

Researchers used measurements of martian neutrons combined with height measurements from the laser altimeter on another NASA spacecraft, Mars Global Surveyor, to monitor the amount of dry ice during the northern winter and spring seasons.

“Once the carbon-dioxide layer disappears, we see even more water ice in northern latitudes than Odyssey found last year in southern latitudes,” said Odyssey’s Dr. Igor Mitrofanov of the Russian Space Research Institute (IKI), Moscow, lead author of a paper in the June 27 issue of the journal Science. “In some places, the water ice content is more than 90 percent by volume,” he said. Mitrofanov and co-authors used the changing nature of the relief of these regions, measured more than 2 years ago by the Global Surveyor’s laser altimeter science team, to explore the implications of the changes.

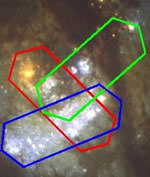

Mars Odyssey’s trio of instruments, called the gamma-ray spectrometer suite, can identify elements in the top meter (3 feet) or so of Mars’ surface. Mars Global Surveyor’s laser altimeter is precise enough to monitor meter-scale changes in the thickness of the seasonal frost, which can accumulate to depths greater than a meter. The new findings show a correlation in the springtime between Odyssey’s detection of dissipating carbon dioxide in latitudes poleward of 65 degrees north and Global Surveyor’s measurement of the thinning of the frost layer in prior years.

“Odyssey’s high-energy neutron detector allows us to measure the thickness of carbon dioxide at lower latitudes, where Global Surveyor’s altimeter does not have enough sensitivity,” Mitrofanov said. “On the other hand, the neutron detector loses sensitivity to measure carbon-dioxide thickness greater than one meter (3 feet), where the altimeter obtained reliable data. Working together, we can examine the whole range of dry-ice snow accumulations.”

“The synergy between the measurements from our two ‘eyes in the skies of Mars’ has enabled these new findings about the nature of near-surface frozen materials, and suggests compelling places to visit in future missions in order to understand habitats on Mars,” said Dr. Jim Garvin, NASA’s Lead Scientist for Mars Exploration.

Another report, to be published in the Journal of Geophysical Research-Planets, combines measurements from Odyssey and Global Surveyor to provide indications of how densely the winter layer of carbon-dioxide frost or snow is packed at northern latitudes greater than 85 degrees. The Odyssey data are used to estimate the mass of the deposit, which can then be compared with the thickness to obtain a density. The dry-ice layer appears to have a fluffy texture, like freshly fallen snow, according to the report by Dr. William Feldman of Los Alamos National Laboratory, N.M., and 11 co-authors. The study also found that once the dry ice disappears, the remaining surface near the pole is composed almost entirely of water ice.

“Mars is constantly changing,” said Dr. Jeffrey Plaut, Mars Odyssey project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif. With Mars Odyssey, we plan to examine these dynamics through additional seasons, to watch how the winter accumulations of carbon dioxide on each pole interact with the atmosphere in the current climate regime.”

Mitrofanov’s co-authors include researchers at the Institute for Space Research of the Russian Academy of Science, Moscow; MIT, Cambridge, MA; NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.; TechSource, Santa Fe, N.M.; and NASA Headquarters, Washington. Feldman’s co-authors include researchers at New Mexico State University, Las Cruces; Cornell University, Ithaca, N.Y.; and Observatoire Midi-Pyrenees, Toulouse, France.

JPL manages the Mars Odyssey and Mars Global Surveyor missions for NASA’s Office of Space Science in Washington. Investigators at Arizona State University, the University of Arizona, and NASA’s Johnson Space Center, Houston, built and operate Odyssey science instruments. The Russian Aviation and Space Agency supplied the high-energy neutron detector and Los Alamos National Laboratory supplied the neutron spectrometer. NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center supplied Global Surveyor’s laser altimeter. Information about NASA’s Mars exploration program is available online at: http://mars.jpl.nasa.gov

Original Source: NASA/JPL News Release