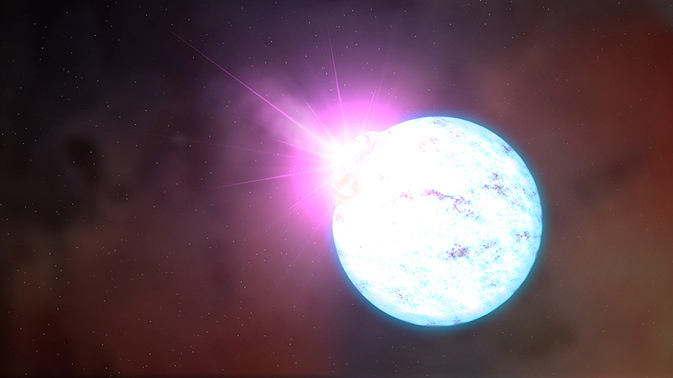

Ever since they were first discovered in the 1930s, scientists have puzzled over the mystery that is neutron stars. These stars, which are the result of a supernova explosion, are the smallest and densest stars in the Universe. While they typically have a radius of about 10 km (6.2 mi) – about 1.437 x 10-5 times that of the Sun – they also average between 1.4 and 2.16 Solar masses.

At this density, which is the same as that of atomic nuclei, a single teaspoon of neutron star material would weigh about as much as 90 million metric tons (100 million US tons). And now, a team of scientists has conducted a study that indicates that the strongest known material in the Universe – what they refer to as “nuclear pasta” – exists deep inside the crust of neutron stars.