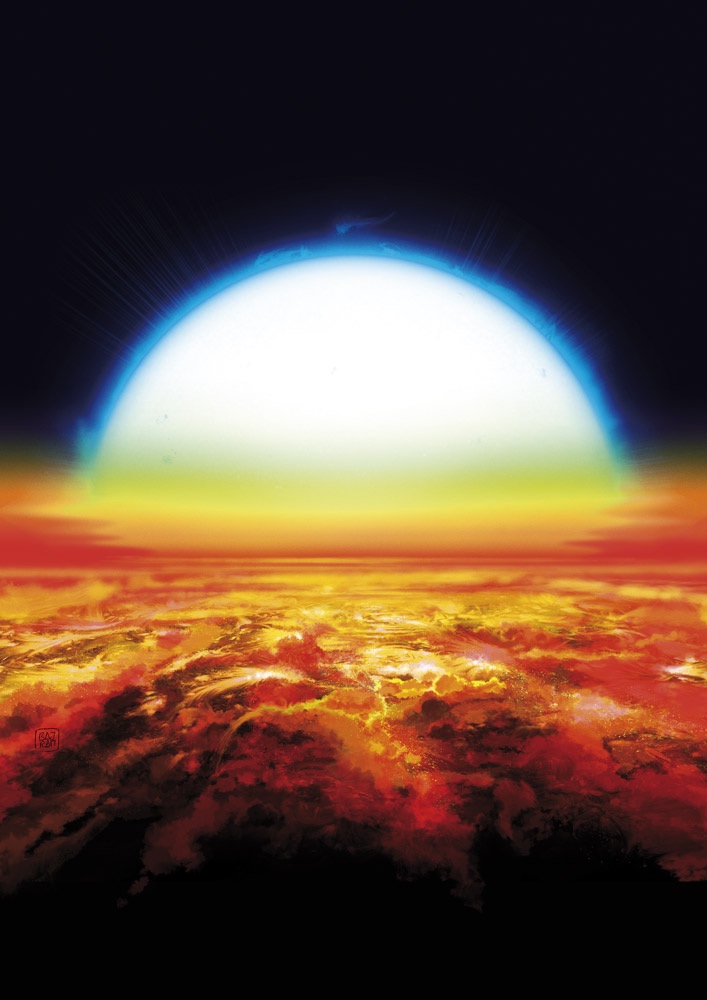

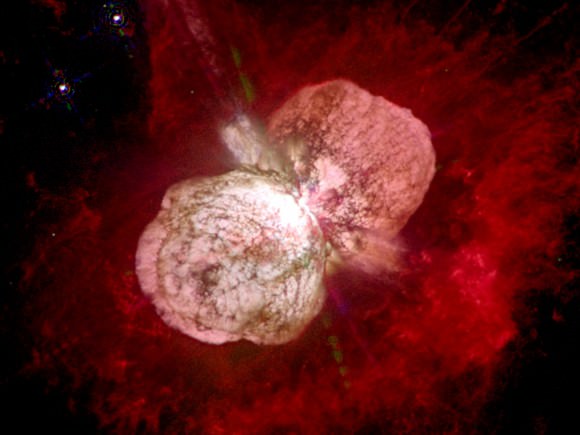

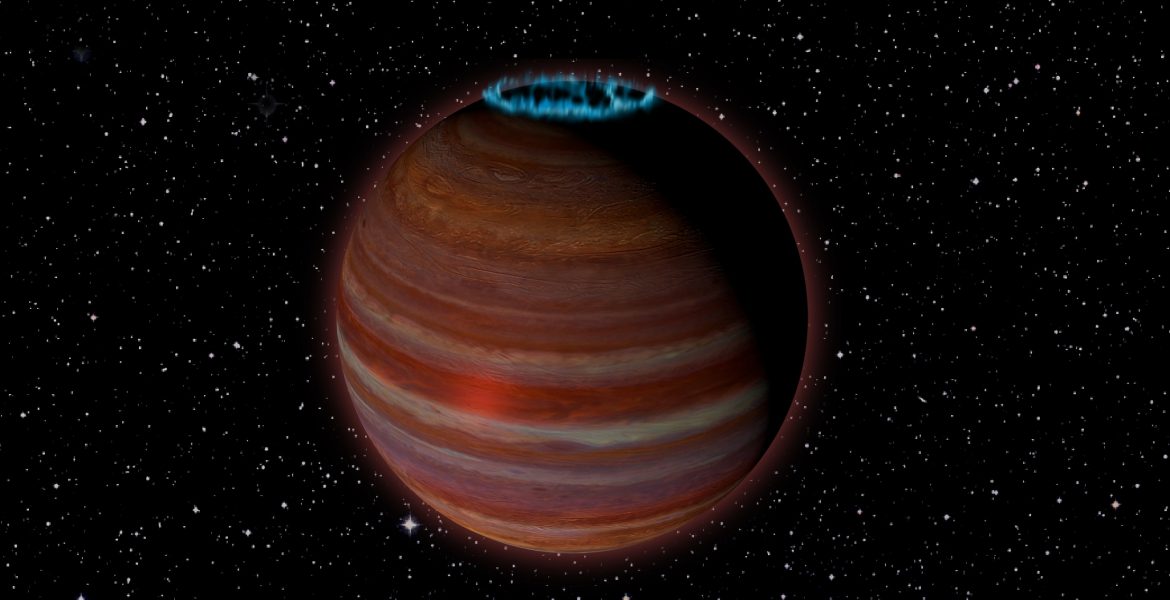

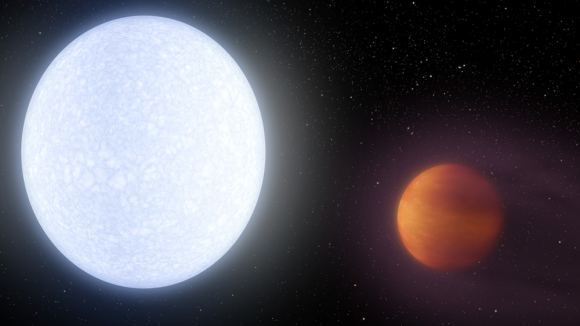

In the course of discovering planets beyond our Solar System, astronomers have found some truly interesting customers! In addition to “Super-Jupiters” (exoplanets that are many times Jupiter’s mass) a number of “Hot Jupiters” have also been observed. These are gas giants that orbit closely to their stars, and in some cases, these planets have been found to be so hot that they could melt stone or metal.

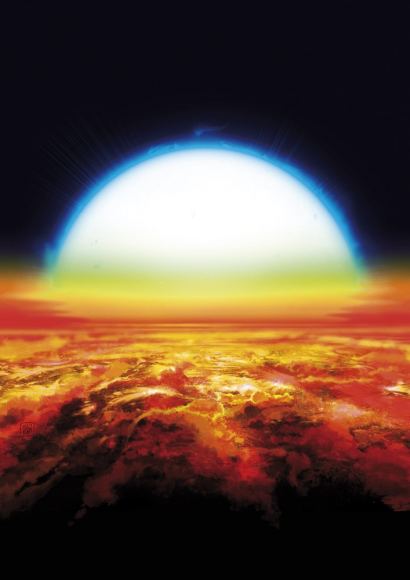

This has led to the designation “ultra-hot Jupiter”, the hottest of which was discovered last year. But now, according to a recent study made by an international team of astronomers, this planet is hot enough to turn metal into vapor. It is known as KELT-9b, a gas giant located 650 light-years from Earth that has atmospheric temperatures so hot – over 4,000 °C (7,232 °F) – it can vaporize iron and titanium!

The international team was led by Jens Hoeijmakers, a postdoctoral student at the University of Geneva (UNIGE) and the the University of Bern (UNIBE). The team included members from the National Center of Competence in Research (NCCR) PlanetS group and UNIGE’s Future of Upper Atmospheric Characterization of Exoplanets with Spectroscopy (FOUR ACES1) team.

These groups, which are dedicated to characterizing exoplanets, are made up of researchers from UNIGE, UNIBE, the University of Zurich (UZH) and the University of Lausanne (UNIL). Additional support came from researchers from Cambridge University’s Cavendish Astrophysics and MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, the Cagliari Observatory, and the Roque de los Muchachos Observatory.

The study which describes their findings – “Atomic iron and titanium in the atmosphere of the exoplanet KELT-9b” – recently appeared in the scientific journal Nature. For the sake of their study, the team sought to place constraints on the chemical composition of an ultra-hot Jupiter since these planets straddle the boundary between gas giants and stars and could help astronomers learn more about exoplanet formation history.

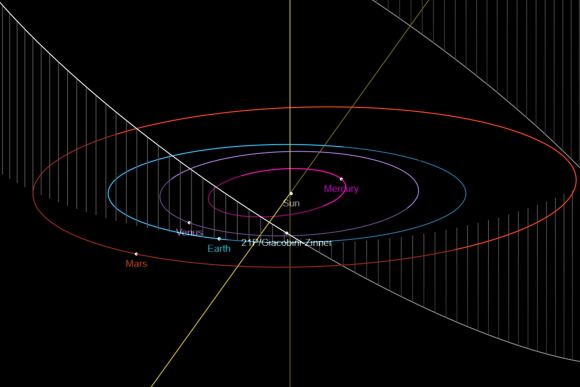

To do this, they selected KELT-9b, which was originally discovered in 2017 by astronomers using the Kilodegree Extremely Little Telescope(s) (KELT) survey. Like all ultra-hot Jupiters, this planet orbits very close to its star – 30 times closer than the Earth’s distance from the Sun – and has a orbital period of 36 hours. As a result, it experiences surface temperatures in excess of 4,000 °C (7,232 °F), making it hotter than many stars.

Based on this, Dr. Hoeijmakers and his colleagues conducted a theoretical study that predicted the presence of iron vapor in the planet’s atmosphere. As Kevin Heng, a professor at the UNIBE and a co-author on the study, explained in a recent UNIGE press release:

“The results of these simulations show that most of the molecules found there should be in atomic form, because the bonds that hold them together are broken by collisions between particles that occur at these extremely high temperatures.”

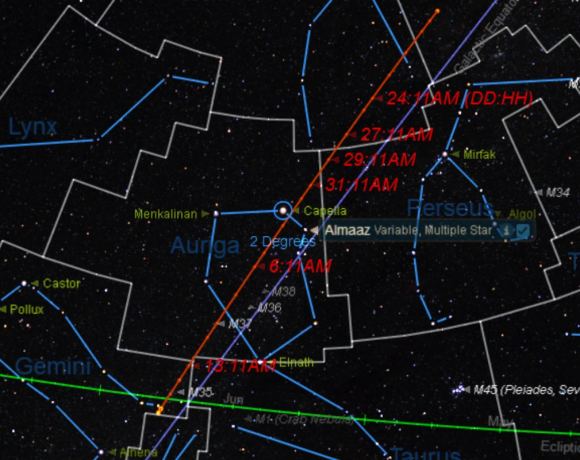

To test this prediction, the team relied on data from the High Accuracy Radial velocity Planet Searcher for the Northern hemisphere (HARPS-North or HARPS-N) spectrograph during a single transit of the exoplanet. During a transit, light from the star can been seen filtering through the atmosphere, and examining this light with a spectrometer can reveal things about the atmosphere’s chemical composition.

What they found were strong indications of not only singly-ionized atomic iron but singly-ionized atomic titanium, which has a significantly higher melting point – 1670 °C (3040 °F) compared to 1250 °C (2282 °F). As Hoeijmakers explained, “With the theoretical predictions in hand, it was like following a treasure map, and when we dug deeper into the data, we found even more.”

In addition to revealing the composition of a new class of ultra-hot Jupiter, this study has also presented astronomers with something of a mystery. For example, scientists believe that many planets have evaporated due to being in a tight orbit with a bright star in the same way that KELT-9b is. And, as their study indicates, the star’s radiation is breaking down heavy transition metals like iron and titanium.

Although KELT-9b is probably too massive to ever totally evaporate, this new study demonstrates the strong impact that stellar radiation has on the composition of a planet’s atmosphere. On cooler gas giants, elements like iron and titanium are believed to take the form of gaseous oxides or dust particles, which are difficult to detect. But in the case of KELT-9b, the fact that these elements are in atomized form makes them highly detectable.

As David Ehrenreich, the principal investigator with the UNIGE’s FOUR ACES team and a co-author on the study, concluded,“This planet is a unique laboratory to analyze how atmospheres can evolve under intense stellar radiation.” Looking ahead, the team’s study also predicts that it should be possible to observe gaseous atomic iron in the planet’s atmosphere using current telescopes.

In short, astronomers need not wait for next-generation telescopes in order to study this unique planetary laboratory, which can teach astronomers much about the process of exoplanet formation. And in by learning more about the formation of gas giants in other star systems, astronomers are likely to gain vital clues as to how our own Solar System formed and evolved.

Who knows? Perhaps our own Jupiter was hot at one time, and lost mass before it migrating to its current position. Or perhaps Mercury is the burnt-out husk of a once giant planet that lost its gaseous layers. As the study of exoplanets is teaching us, such strange things are known to happen in this Universe!

Further Reading: University of Geneva, Nature