The Moon and Mars will probably be the first places in the Solar System that humanity will try to live after leaving the safety and security of Earth. But those worlds are still incredibly harsh environments, with no protection from radiation, little to no atmosphere, and extreme temperatures.

Living on those worlds is going to be hard, it’s going to be dangerous. Fortunately, there are a few pockets on those worlds that’ll make it a tiny little bit easier to get a foothold in the Solar System: lava tubes.

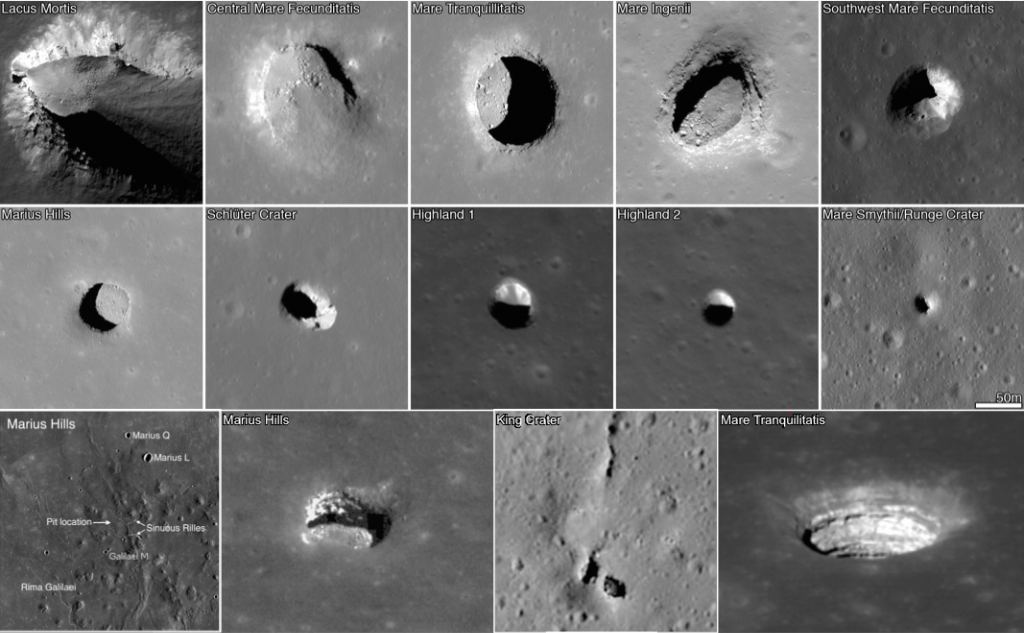

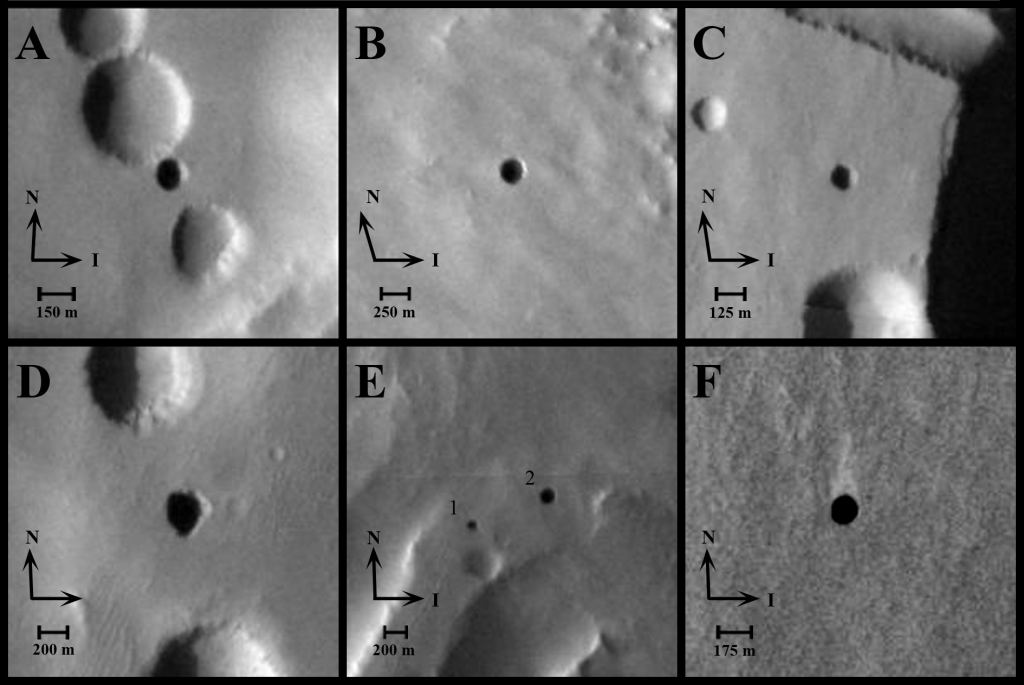

I’m going to show you some really cool photographs now. First, let’s start with images of the Moon taken by NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter.

Those dark blobs in the photo are actually open skylights, the collapsed roofs of lava tubes on the Moon. They just look like dark areas because you can’t see the bottom. How cool is that?

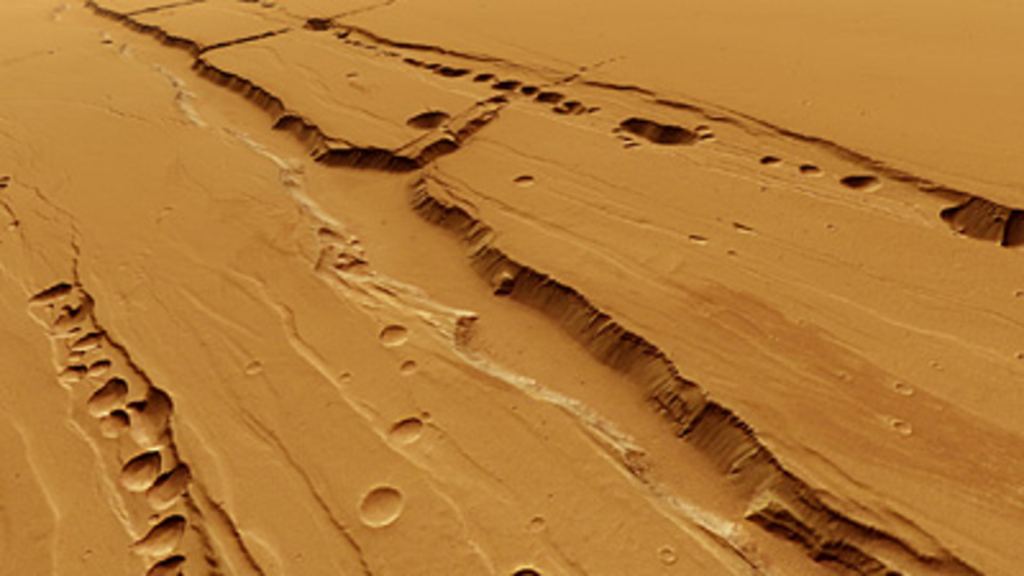

And now, here are similar features on the surface of Mars. Here are several examples of cave skylights across the Red Planet.

And I want to show you a really special one. Check out this photo, where you can see the cave opening, how the Martian sand is flowing down into the skylight. You can even see it piling up on the cave floor. There’s no question, this is a cavern on Mars with opening to the surface.

Want to live on the Moon or Mars? You’re looking at your future home.

Lava tubes are a common here on Earth, and you can find them wherever there’s been volcanic activity. During an eruption, lava gets flowing downhill through a channel. The surface cools and crusts over, but the lava keeps on flowing, like an underground river of molten rock.

In the right conditions, the lava can keep flowing, and empty out the channel completely, leaving behind a natural tunnel that can be dozens of kilometers long. The tubes can be wide, from a single meter to up to 15 meters wide. Definitely big enough to live inside.

Both the Moon and Mars had periods of volcanism. The biggest volcano in the Solar System, Olympus Mons on Mars, is an enormous shield volcano with endless lava fields surrounding it.

The SETI Institute recently announced that they had identified a series of small pits in a crater near the Moon’s northern pole. They found them by analyzing images taken by NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter.

They look like skylights, and match similar features on Mars, where there is no crater rim, and just a shadowed dark feature. Further evidence is that they lie along lunar sinuous rilles, those ancient lava rivers with collapses features in a row.

At this point, there have been about 200 of these features discovered on the Moon so far, and more discovered on Mars too.

In addition to the skylights discovered by spacecraft, planetary scientists have uncovered vast pit chains on Mars, which could be collapsed lava tubes. With the amount of volcanism that occured on Mars over billions of years, there should be many features worth exploring.

Because of the lower gravity on the Moon and Mars, lava tubes should be much more extreme. On Mars, there could be lava tubes that measure hundreds of meters across, and hundreds of kilometers long. On the Moon, lava tubes could be kilometers across. Big enough to hide a city inside.

Future Moon and Mars colonists will already be facing a life underground, to hide from the surface radiation, micrometeorite bombardment, extreme temperatures and to create a usable atmosphere. These natural tunnels will save them the hard work of needing to dig the tunnel.

The natural roofs on these caverns are thought to be 10 meters or more thick, with one site estimated to have a roof that’s 45-90 meters thick. This would be more than enough to protect against solar radiation and galactic cosmic radiation.

While the surface of the Moon varies in temperature from -180 C to +100 C, the interior of a lava tube would remain a constant chilly -20 C. This would be easy enough to keep warmed up, once it was sealed off and pressurized with a breathable atmosphere.

As we’ve mentioned time and time again, the lunar dust on the Moon is dangerous stuff, irritating eyes, nasal passages and lungs. Lunar colonists would want to minimize their exposure to it at all costs. By sealing off the interior of the lava tube, they could prevent further dust from getting in. In fact, the dust is also electrically charged, and could be a hazard to electronics.

In terms of resources, the Moon has plenty. There’s aluminum everywhere in the regolith, as well as iron and titanium. But the most valuable one for humans, water, could be down there too. In the eternally shadowed craters, there could be large deposits of water collected down below that colonists could harvest.

There’s another advantage, the lava tubes on Mars could be the best places to search for life on the Red Planet. The natural protection would also keep Martian bacteria less exposed to the harsh conditions of the surface.

Future explorers could be protected inside the lava tubes at the same time that they’re in the ideal place to search for life on Mars. That’s convenient.

Of course NASA and the European Space Agency have considered human and robotic missions that could travel to the Moon or Mars and explore the interiors of lava tubes.

In 2011, a group of researchers proposed a mission design for a combined lander-rover that would map out a skylight on the Moon in incredible detail. It’s known as the Marius Hills Hole, and measures about 65 meters across.

First, the lander would descend down to the surface of the Moon near the hole, using a pulsed laser called LIDAR to map out a 50-meter region around the landing site, looking for hazards.

The spacecraft would then choose a landing site and deploy a rover that would scan the region around the skylight in extreme detail, peeking down into the lava tube when the light is right.

Following that, would come the missions to actually explore down in the tunnels. Remember how big they are, potentially hundreds of meters and even kilometers across.

You can imagine various robotic rovers and landers, but one of my favorite ideas is a snake robot developed by SINTEF in Norway. The robot uses hydraulics to move segments of its body, allowing it to move like a real snake. It could climb stairs, navigate up and down slopes, go around corners, and be able to handle the unpredictable terrain of the floor of a lavatube.

After the robots come the humans. The tricky part is getting from the surface down to the tunnel floor. Mission planners have proposed traditional rappelling and even astronauts with jetpacks who would lower themselves down into the tunnel to explore around.

The first astronauts would descend down to the floor of the lava tube bringing quadruped pack mule robots that would be able to navigate the rough terrain of the tunnel floor. Once inside, they’d set up a communications link at the crater opening, and then deploy a pressurized tent as a temporary habitat.

The astronauts would be free to travel several kilometers into the lava tube, mapping the interior, and taking samples. They could set up their tent at different points, allowing a much deeper exploration.

Of course, then hostile cave aliens would pick them off one by one, and the only way we’d know about the mission is from a series of found footage and computer logs. But I digress.

The European Space Agency has been developing tools to measure the interior of caves here on Earth, to develop the technology that could be used to explore other worlds. You’re looking at a 3D image of the interior of a cave network in Spain.

A team of researchers, including a European astronaut, used backpack-based cameras and LIDAR instruments to map out the cave to a resolution of just a few centimeters. They also tested out handheld tools to examine the cave walls, doing the same kinds of experiments future astronauts might do.

The long term goal, of course, is to set up some kind of long term colony inside lava tubes on the Moon or Mars.

What started as a temporary hiding place from the brutal environment of the Moon and Mars would become the base of operations for a future habitat and eventually the beginnings of a scientific outpost or even a full colony.

There’s no question that lava tubes are going to be one of the top priorities when we return to the Moon, and when the first astronaut sets foot on Mars. And with all the new missions in the works, from both NASA, SpaceX, the Europeans and even the Chinese, it looks like those days aren’t too far off now.