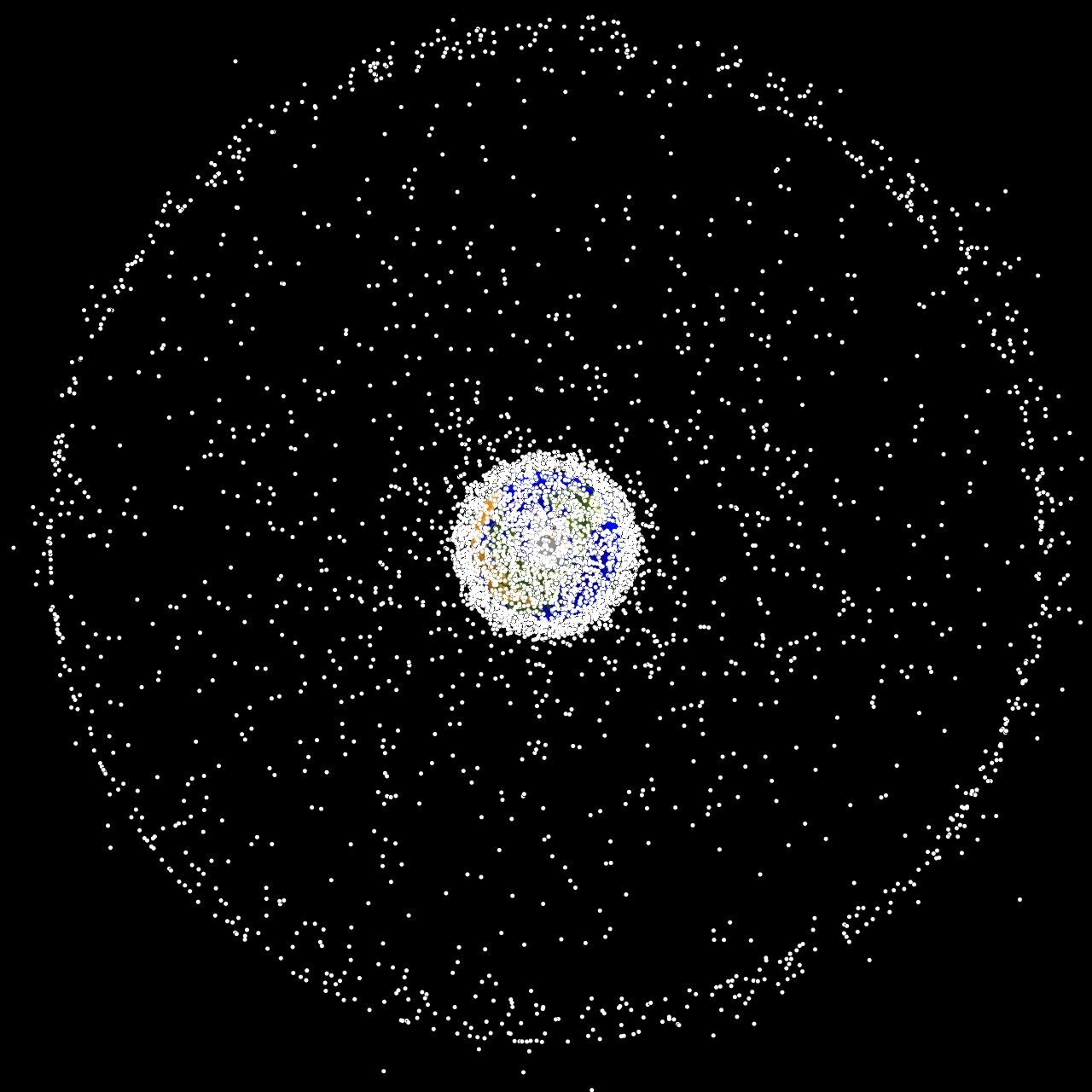

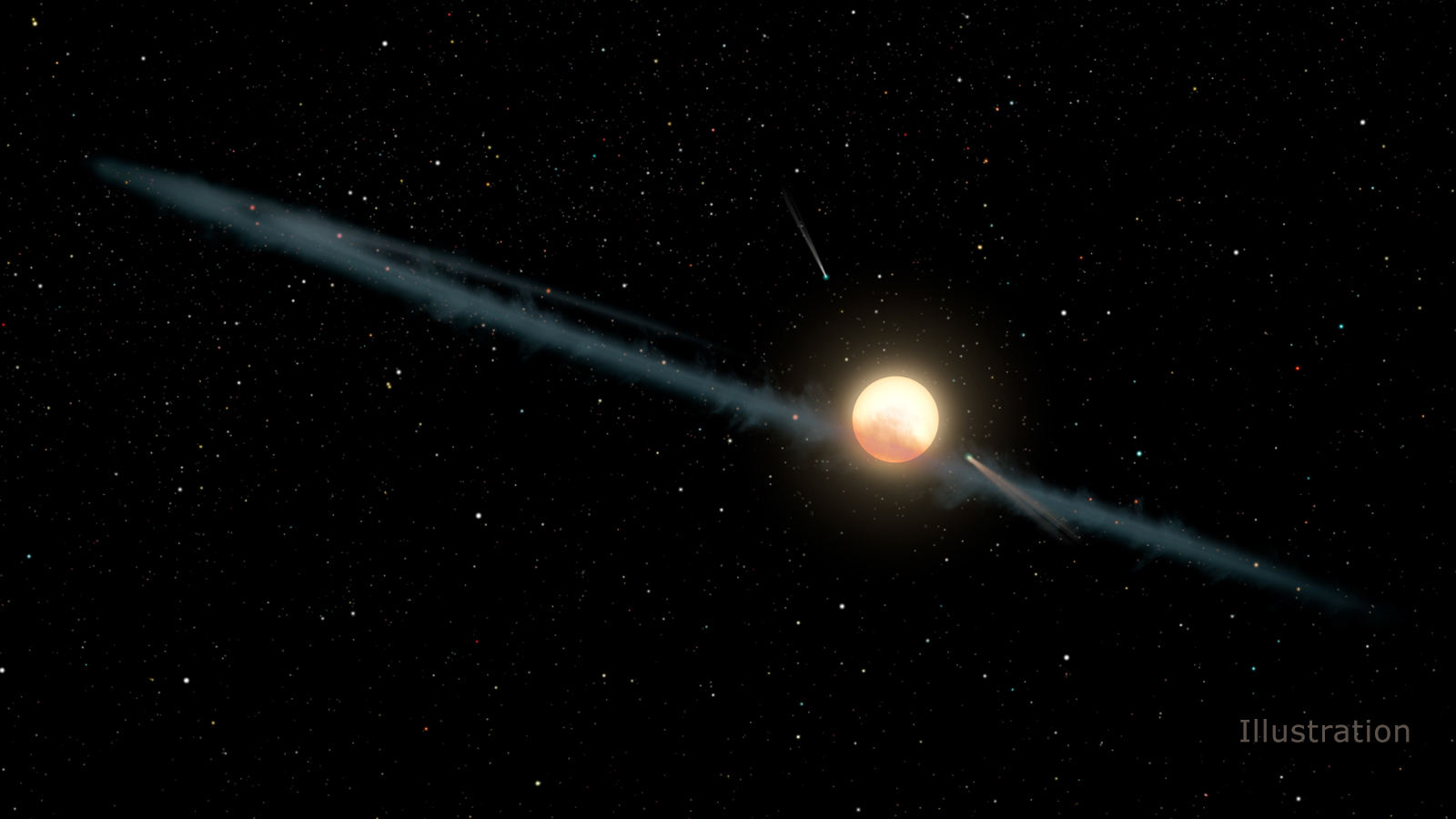

When searching for extra-solar planets, astronomers most often rely on a number of indirect techniques. Of these, the Transit Method (aka. Transit Photometry) and the Radial Velocity Method (aka. Doppler Spectroscopy) are the two most effective and reliable (especially when used in combination). Unfortunately, direct imaging is rare since it is very difficult to spot a faint exoplanet amidst the glare of its host star.

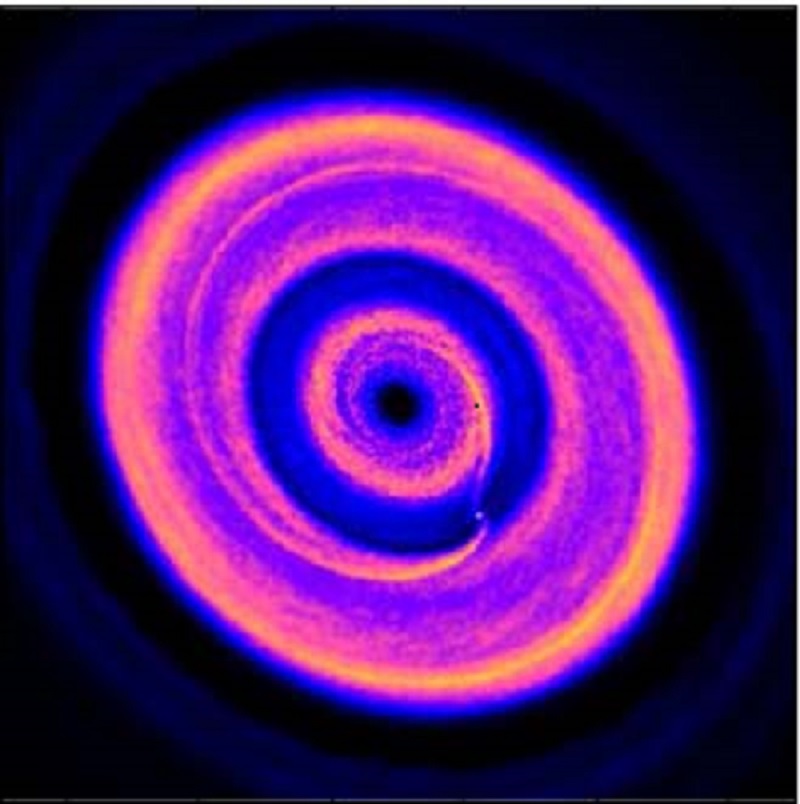

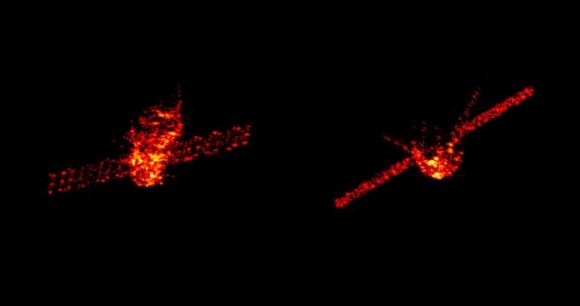

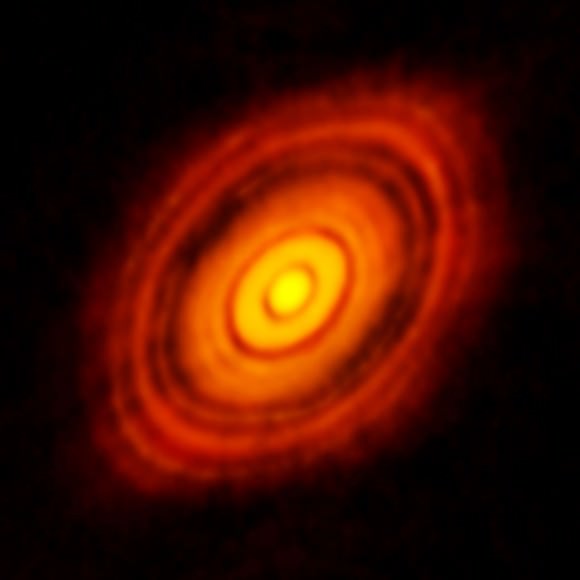

However, improvements in radio interferometers and near-infrared imaging has allowed astronomers to image protoplanetary discs and infer the orbits of exoplanets. Using this method, an international team of astronomers recently captured images of a newly-forming planetary system. By studying the gaps and ring-like structures of this system, the team was able to hypothesize the possible size of an exoplanet.

The study, titled “Rings and gaps in the disc around Elias 24 revealed by ALMA “, recently appeared in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. The team was led by Giovanni Dipierro, an astrophysicist from the

In the past, rings of dust have been identified in many protoplanetary systems, and their origins and relation to planetary formation are the subject of much debate. On the one hand, they might be the result of dust piling up in certain regions, of gravitational instabilities, or even variations in the optical properties of the dust. Alternately, they could be the result of planets that have already developed, which cause the dust to dissipate as they pass through it.

As Dipierro and his colleagues explained in their study:

“The alternative scenario invokes discs that are dynamically active, in which planets have already formed or are in the act of formation. An embedded planet will excite density waves in the surrounding disc, that then deposit their angular momentum as they are dissipated. If the planet is massive enough, the exchange of angular momentum between the waves created by the planet and the disc results in the formation of a single or multiple gaps, whose morphological features are closely linked to the local disc conditions and the planet properties.”

For the sake of their study, the team used data from the Atacama Large Millimeter/sub-millimeter Array (ALMA) Cycle 2 observations – which began back in June of 2014. In so doing, they were able to image the dust around Elias 24 with a resolution of about 28 AU (i.e. 28 times the distance between the Earth and the Sun). What they found was evidence of gaps and rings that could be an indication of an orbiting planet.

From this, they constructed a model of the system that took into account the mass and location of this potential planet and how the distribution and density of dust would cause it to evolve. As they indicate in their study, their model reproduces the observations of the dust ring quite well, and predicted the presence of a Jupiter-like gas giant within forty-four thousand years:

“We find that the dust emission across the disc is consistent with the presence of an embedded planet with a mass of ?0.7?MJ at an orbital radius of ? 60?au… The surface brightness map of our disc model provides a reasonable match to the gap- and ring-like structures observed in Elias 24, with an average discrepancy of ?5?per?cent of the observed fluxes around the gap region.”

These results reinforce the conclusion that the gaps and rings that have been observed in a wide variety of young circumstellar discs indicate the presence of orbiting planets. As the team indicated, this is consistent with other observations of protoplanetary discs, and could help shed light on the process of planetary formation.

“The picture that is emerging from the recent high resolution and high sensitivity observations of protoplanetary discs is that gap and ring-like features are prevalent in a large range of discs with different masses and ages,” they conclude. “New high resolution and high fidelity ALMA images of dust thermal and CO line emission and high quality scattering data will be helpful to find further evidences of the mechanisms behind their formation.”

One of the toughest challenges when it comes to studying the formation and evolution of planets is the fact that astronomers have been traditionally unable to see the processes in action. But thanks to improvements in instruments and the ability to study extra-solar star systems, astronomers have been able to see system’s at different points in the formation process.

This in turn is helping us refine our theories of how the Solar System came to be, and may one day allow us to predict exactly what kinds of systems can form in young star systems.