This week’s Carnival of Space is hosted by Gadi Eidelheit at his The Venus Transit blog.

Click here to read Carnival of Space #550.

Continue reading “Carnival of Space #550”

Space and astronomy news

This week’s Carnival of Space is hosted by Gadi Eidelheit at his The Venus Transit blog.

Click here to read Carnival of Space #550.

Continue reading “Carnival of Space #550”

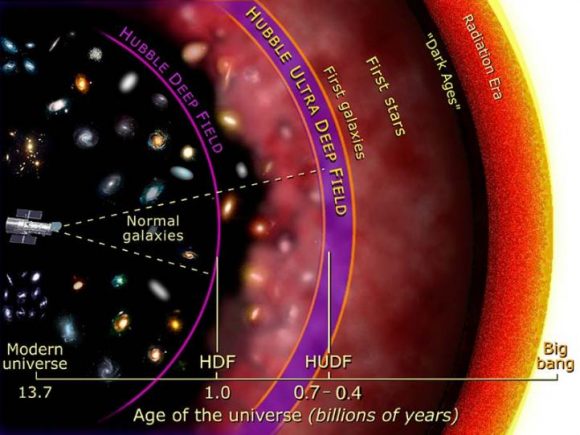

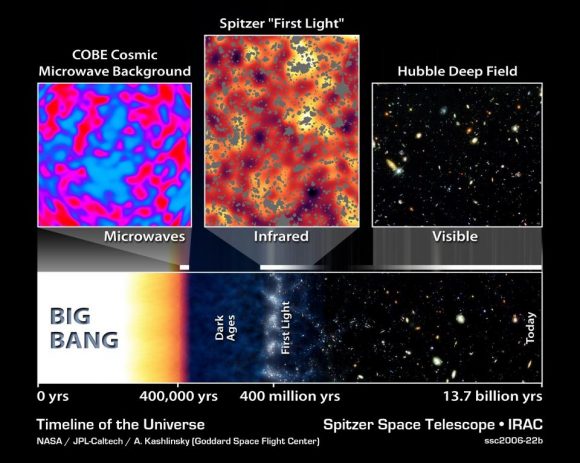

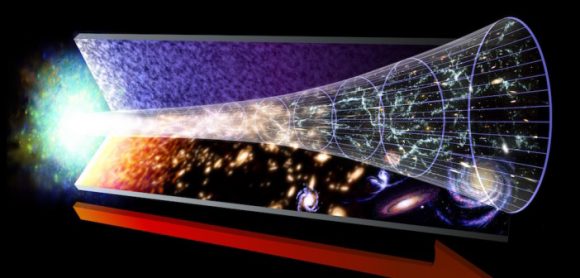

In the 1920s, Edwin Hubble made the groundbreaking revelation that the Universe was in a state of expansion. Originally predicted as a consequence of Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity, this confirmation led to what came to be known as Hubble’s Constant. In the ensuring decades, and thanks to the deployment of next-generation telescopes – like the aptly-named Hubble Space Telescope (HST) – scientists have been forced to revise this law.

In short, in the past few decades, the ability to see farther into space (and deeper into time) has allowed astronomers to make more accurate measurements about how rapidly the early Universe expanded. And thanks to a new survey performed using Hubble, an international team of astronomers has been able to conduct the most precise measurements of the expansion rate of the Universe to date.

This survey was conducted by the Supernova H0 for the Equation of State (SH0ES) team, an international group of astronomers that has been on a quest to refine the accuracy of the Hubble Constant since 2005. The group is led by Adam Reiss of the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) and Johns Hopkins University, and includes members from the American Museum of Natural History, the Neils Bohr Institute, the National Optical Astronomy Observatory, and many prestigious universities and research institutions.

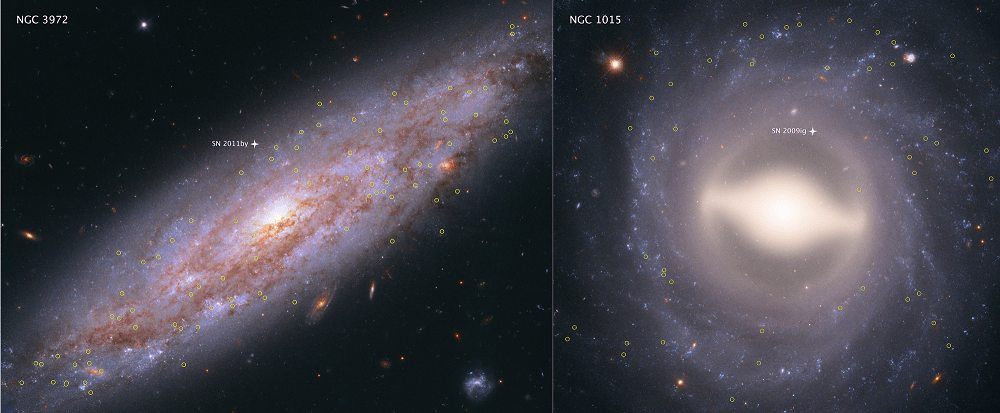

The study which describes their findings recently appeared in The Astrophysical Journal under the title “Type Ia Supernova Distances at Redshift >1.5 from the Hubble Space Telescope Multi-cycle Treasury Programs: The Early Expansion Rate“. For the sake of their study, and consistent with their long term goals, the team sought to construct a new and more accurate “distance ladder”.

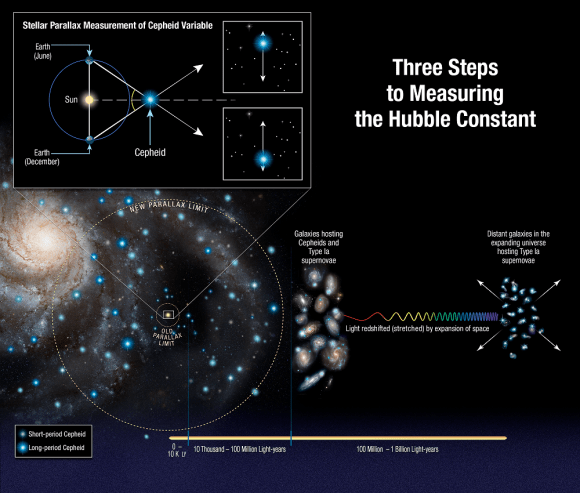

This tool is how astronomers have traditionally measured distances in the Universe, which consists of relying on distance markers like Cepheid variables – pulsating stars whose distances can be inferred by comparing their intrinsic brightness with their apparent brightness. These measurements are then compared to the way light from distance galaxies is redshifted to determine how fast the space between galaxies is expanding.

From this, the Hubble Constant is derived. To build their distant ladder, Riess and his team conducted parallax measurements using Hubble’s Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3) of eight newly-analyzed Cepheid variable stars in the Milky Way. These stars are about 10 times farther away than any studied previously – between 6,000 and 12,000 light-year from Earth – and pulsate at longer intervals.

To ensure accuracy that would account for the wobbles of these stars, the team also developed a new method where Hubble would measure a star’s position a thousand times a minute every six months for four years. The team then compared the brightness of these eight stars with more distant Cepheids to ensure that they could calculate the distances to other galaxies with more precision.

Using the new technique, Hubble was able to capture the change in position of these stars relative to others, which simplified things immensely. As Riess explained in a NASA press release:

“This method allows for repeated opportunities to measure the extremely tiny displacements due to parallax. You’re measuring the separation between two stars, not just in one place on the camera, but over and over thousands of times, reducing the errors in measurement.”

Compared to previous surveys, the team was able to extend the number of stars analyzed to distances up to 10 times farther. However, their results also contradicted those obtained by the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Planck satellite, which has been measuring the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) – the leftover radiation created by the Big Bang – since it was deployed in 2009.

By mapping the CMB, Planck has been able to trace the expansion of the cosmos during the early Universe – circa. 378,000 years after the Big Bang. Planck’s result predicted that the Hubble constant value should now be 67 kilometers per second per megaparsec (3.3 million light-years), and could be no higher than 69 kilometers per second per megaparsec.

Based on their sruvey, Riess’s team obtained a value of 73 kilometers per second per megaparsec, a discrepancy of 9%. Essentially, their results indicate that galaxies are moving at a faster rate than that implied by observations of the early Universe. Because the Hubble data was so precise, astronomers cannot dismiss the gap between the two results as errors in any single measurement or method. As Reiss explained:

“The community is really grappling with understanding the meaning of this discrepancy… Both results have been tested multiple ways, so barring a series of unrelated mistakes. it is increasingly likely that this is not a bug but a feature of the universe.”

These latest results therefore suggest that some previously unknown force or some new physics might be at work in the Universe. In terms of explanations, Reiss and his team have offered three possibilities, all of which have to do with the 95% of the Universe that we cannot see (i.e. dark matter and dark energy). In 2011, Reiss and two other scientists were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for their 1998 discovery that the Universe was in an accelerated rate of expansion.

Consistent with that, they suggest that Dark Energy could be pushing galaxies apart with increasing strength. Another possibility is that there is an undiscovered subatomic particle out there that is similar to a neutrino, but interacts with normal matter by gravity instead of subatomic forces. These “sterile neutrinos” would travel at close to the speed of light and could collectively be known as “dark radiation”.

Any of these possibilities would mean that the contents of the early Universe were different, thus forcing a rethink of our cosmological models. At present, Riess and colleagues don’t have any answers, but plan to continue fine-tuning their measurements. So far, the SHoES team has decreased the uncertainty of the Hubble Constant to 2.3%.

This is in keeping with one of the central goals of the Hubble Space Telescope, which was to help reduce the uncertainty value in Hubble’s Constant, for which estimates once varied by a factor of 2.

So while this discrepancy opens the door to new and challenging questions, it also reduces our uncertainty substantially when it comes to measuring the Universe. Ultimately, this will improve our understanding of how the Universe evolved after it was created in a fiery cataclysm 13.8 billion years ago.

Further Reading: NASA, The Astrophysical Journal

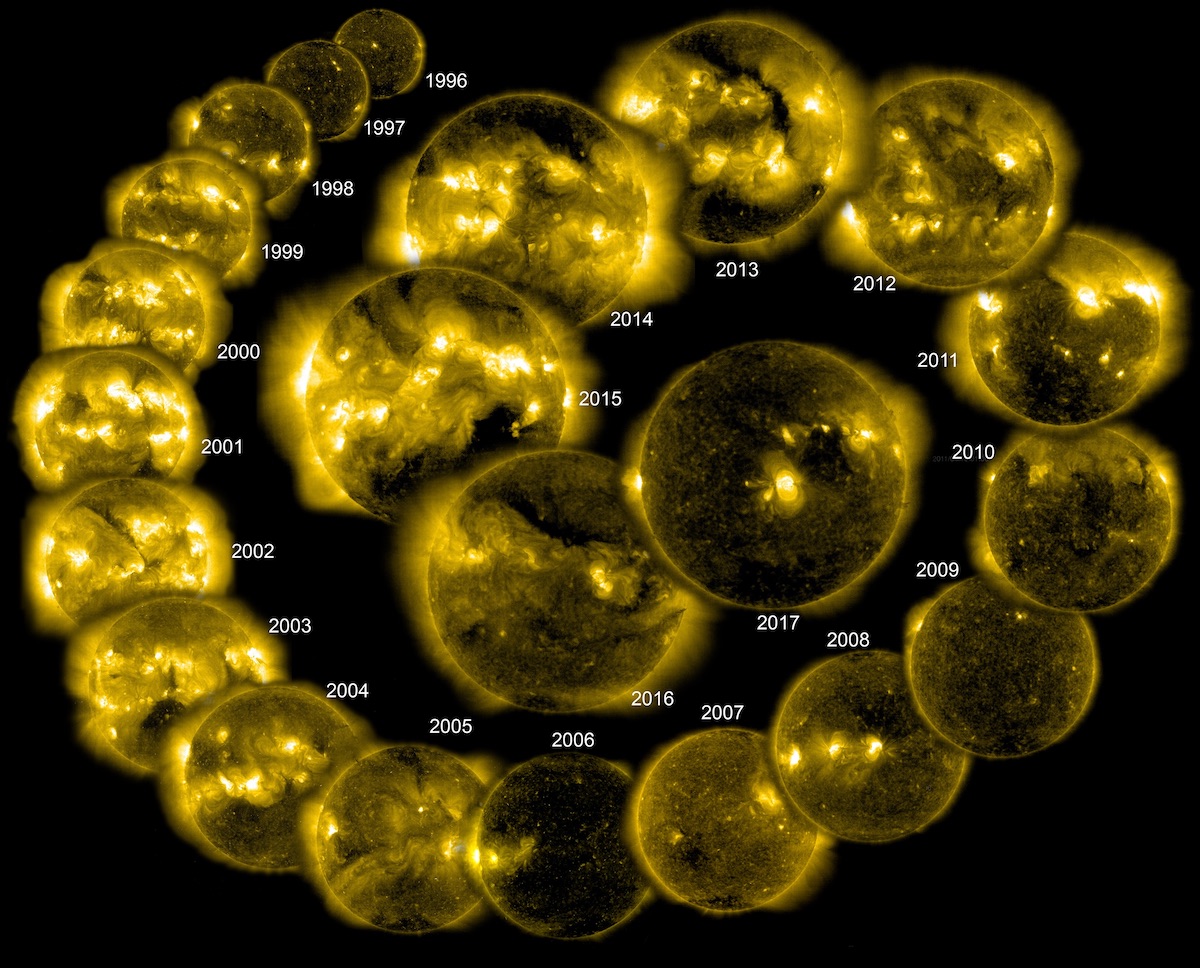

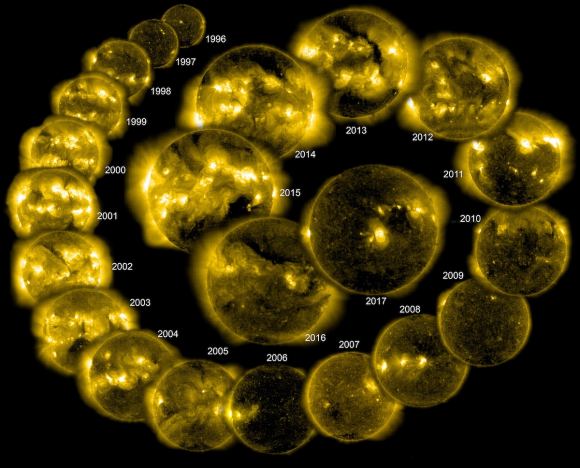

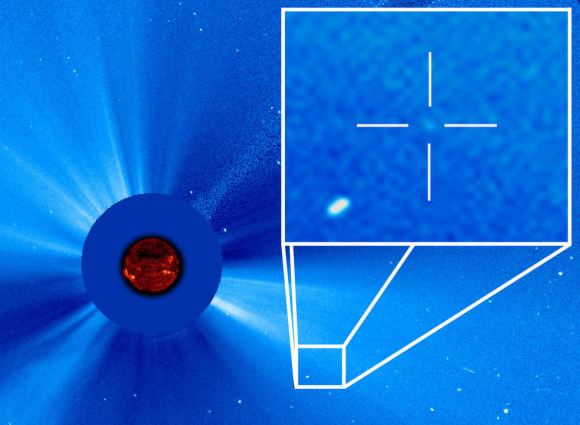

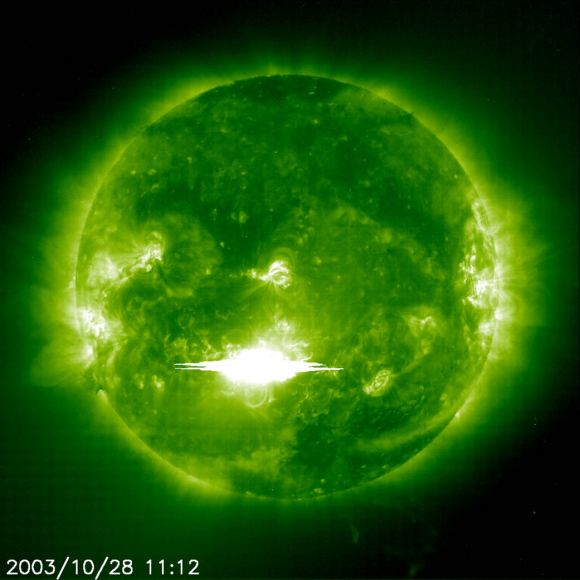

The Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) is celebrating 22 years of observing the Sun, marking one complete solar magnetic cycle in the life of our star. SOHO is a joint project between NASA and the ESA and its mission is to study the internal structure of the sun, its extensive outer atmosphere, and the origin of the solar wind.

The activity cycle in the life of the Sun is based on the increase and decrease of sunspots. We’ve been watching this activity for about 250 years, but SOHO has taken that observing to a whole new level.

Though sunspot cycles work on an 11-year period, they’re caused by deeper magnetic changes in the Sun. Over the course of 22 years, the Sun’s polarity gradually shifts. At the 11 year mark, the orientation of the Sun’s magnetic field flips between the northern and southern hemispheres. At the end of the 22 year cycle, the field has shifted back to its original orientation. SOHO has now watched that cycle in its entirety.

SOHO is a real success story. It was launched in 1995 and was designed to operate until 1998. But it’s been so successful that its mission has been prolonged and extended several times.

SOHO’s 22 years of observation has turbo-charged our space weather forecasting ability. Space weather is heavily influenced by solar activity, mostly in the form of Coronal Mass Ejections (CMEs). SOHO has observed well over 20,000 of these CMEs.

Space weather affects key aspects of our modern technological world. Space-based telecommunications, broadcasting, weather services and navigation are all affected by space weather. So are things like power distribution and terrestrial communications, especially at northern latitudes. Solar weather can also degrade not only the performance, but the lifespan, of communication satellites.

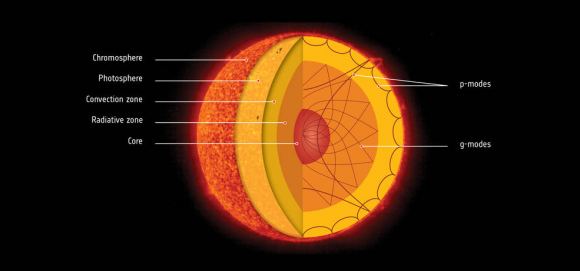

Besides improving our ability to forecast space weather, SOHO has made other important discoveries. After 40 years of searching, it was SOHO that finally found evidence of seismic waves in the Sun. Called g-modes, these waves revealed that the core of the Sun is rotating 4 times faster than the surface. When this discovery came to light, Bernhard Fleck, ESA SOHO project scientist said, “This is certainly the biggest result of SOHO in the last decade, and one of SOHO’s all-time top discoveries.”

SOHO also has a front row seat for comet viewing. The observatory has witnessed over 3,000 comets as they’ve sped past the Sun. Though this was never part of SOHO’s mandate, its exceptional view of the Sun and its surroundings allows it to excel at comet-finding. It’s especially good at finding sun-grazer comets because it’s so close to the Sun.

“But nobody dreamed we’d approach 200 (comets) a year.” – Joe Gurman, mission scientist for SOHO.

“SOHO has a view of about 12-and-a-half million miles beyond the sun,” said Joe Gurman in 2015, mission scientist for SOHO at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “So we expected it might from time to time see a bright comet near the sun. But nobody dreamed we’d approach 200 a year.”

A front-row seat for sun-grazing comets allows SOHO to observe other aspects of the Sun’s surface. Comets are primitive relics of the early Solar System, and observing them with SOHO can tell scientists quite a bit about where they formed. If a comet has made other trips around the Sun, then scientists can learn something about the far-flung regions of the Solar System that they’ve traveled through.

Watching these sun-grazers as they pass close to the Sun also teaches scientists about the Sun. The ionized gas in their tails can illuminate the magnetic fields around the Sun. They’re like tracers that help observers watch these invisible magnetic fields. Sometimes, the magnetic fields have torn off these tails of ionized gas, and scientists have been able to watch these tails get blown around in the solar wind. This gives them an unprecedented view of the details in the movement of the wind itself.

SOHO is still going strong, and keeping an eye on the Sun from its location about 1.5 million km from Earth. There, it travels in a halo orbit around LaGrange point 1. (It’s orbit is adjusted so that it can communicate clearly with Earth without interference from the Sun.)

Beyond the important science that SOHO provides, it’s also a source of amazing images. There’s a whole gallery of images here, and a selection of videos here.

You can also check out daily views of the Sun from SOHO here.

The vast majority of rockets are multi-staged affairs. Why is this? What makes this kind of rocket so successful? Today we look at the ins and outs of multi-stage rockets.

We usually record Astronomy Cast every Friday at 3:00 pm EST / 12:00 pm PST / 20:00 PM UTC. You can watch us live on AstronomyCast.com, or the AstronomyCast YouTube page.

Visit the Astronomy Cast Page to subscribe to the audio podcast!

If you would like to support Astronomy Cast, please visit our page at Patreon here – https://www.patreon.com/astronomycast. We greatly appreciate your support!

If you would like to join the Weekly Space Hangout Crew, visit their site here and sign up. They’re a great team who can help you join our online discussions!

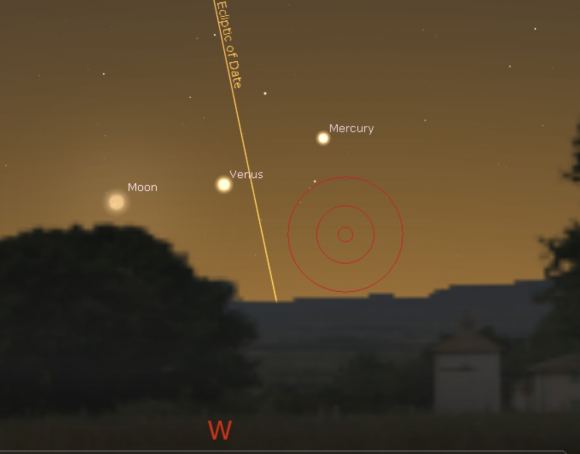

Where have all the planets gone? The end of February 2018 sees the three naked eye outer planets – Mars, Jupiter and Saturn — hiding in the dawn. It takes an extra effort to brave the chill of a February morning, for sure. The good news is, the two inner planets – Mercury and Venus – begin favorable dusk apparitions this week, putting on a fine sunset showing in March.

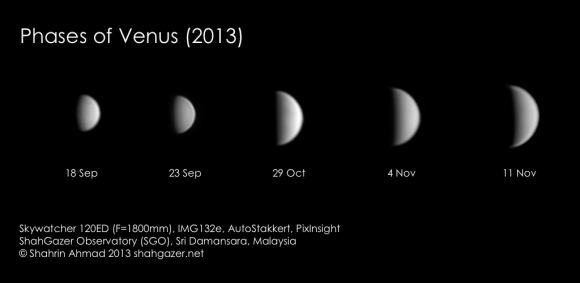

Venus in 2018: Venus begins the month of March as a -3.9 magnitude, 10” disk emerging from behind the Sun. Venus is already over 12 degrees east of the Sun this week, as it begins its long chase to catch up to the Earth. Venus always emerges from behind the Sun in the dusk, lapping the Earth about eight months later as it passes through inferior conjunction between the Sun and the Earth as it ventures into the dusk sky.

Follow that planet, as Venus reaches greatest elongation at 45.9 degrees east of the Sun on August 17th. Venus occupies the apex of a right triangle on this date, with the Earth at the end of one vertice, and the Sun at the end of the other.

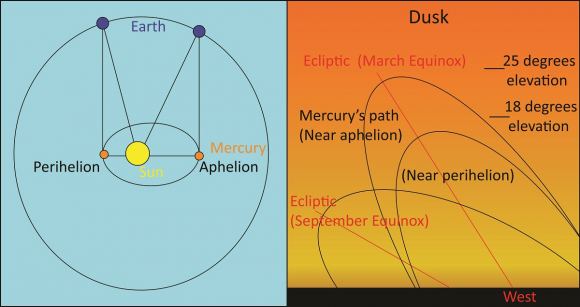

Mercury joins the fray in early March, as the fleeting innermost world races up to meet Venus in the dusk. March 4th is a great date to check Mercury off of your life list, as the -1.2 magnitude planet passes just 66′ – just over a degree, or twice the span of a Full Moon – from Venus. Mercury reaches greatest elongation 18.4 degrees east of the Sun on March 15th.

And the Moon makes three on the evening of March 18th, as Mercury, Venus and the slim waxing crescent Moon form a line nine degrees long.

It’s a bit of a cosmic irony: Venus, the closest planet to the Earth, is also eternally shrouded in clouds and appears featureless at the eyepiece. The most notable feature Venus exhibits are its phases, similar to the Moon’s. Things get interesting as Venus reaches half phase near greatest elongation. After that, the disk of Venus swells in size but thins down to a slender crescent. Venus’s orbit is tilted 3.4 degrees relative to the ecliptic, and on some years, you can follow it right through inferior conjunction from the dusk to the dawn sky. Unfortunately, this also means that Venus usually misses transiting the disk of the Sun, as it last did on June 5-6th, 2012, and won’t do again until just under a century from now on December 10-11th, 2117.

Small consolation prize: Mercury, a much more frequent solar transiter, will do so again next year on November 11-12th, 2019.

Amateur astronomers have, however, managed to tease out detail from the Venusian cloudtops using ultraviolet filters. And check out this amazing recent image of Venus courtesy of the Japanese Space Agency’s Akatsuki spacecraft:

It’s one of our favorite astro-challenges. Can you see Venus in the daytime? Once you’ve seen it, it’s surprisingly easily to spy… the main difficulty is to get your eyes to focus in on it without any other references against a blank sky. The crescent Moon makes a great visual aid in this quest; although the Moon’s reflectivity or albedo is actually much lower than Venus’s, it’s larger apparent size in the sky makes it stand out. Key upcoming dates to see Venus near the Moon around greatest elongation are April 17th, May 17th, June 16th, July 15th, and Aug 14th.

Apparitions of Venus also follow a predictable eight year cycle. This occurs because 13 orbits of Venus very nearly equals eight orbits of the Earth. For example, Venus will resume visiting the Pleiades star cluster during the dusk 2020 apparition, just like it did back before 2012.

Phenomena of Venus

When does Venus appear half illuminated to you? This stage is known as dichotomy, and its actual observed point can often be several days off from its theoretical arrival. Also keep an eye out for the Ashen Light of Venus, a faint illumination of the planet’s night side during crescent phase, similar to the familiar sight seen on the crescent Moon. Unlike the Moon, however, Venus has no nearby body to illuminate its nighttime side… What’s going on here? Is this just the psychological effect of the brain filling in what the eye sees when it looks at the dazzling curve of the crescent Venus, or is it something real? Long reported by observers, a 2014 study suggests that a nascent air-glow or aurora may persist on the broiling night side of Venus.

All thoughts to ponder, as you follow Venus emerging into the dusk sky this March.

The microgravity in space causes a number of problems for astronauts, including bone density loss and muscle atrophy. But there’s another problem: weightlessness allows astronauts’ spines to expand, making them taller. The height gain is permanent while they’re in space, and causes back pain.

A new SkinSuit being tested in a study at King’s College in London may bring some relief. The study has not been published yet.

The constant 24 hour microgravity that astronauts live with in space is different from the natural 24 hour cycle that humans go through on Earth. Down here, the spine goes through a natural cycle associated with sleep.

Sleeping in a supine position allows the discs in the spine to expand with fluid. When we wake up in the morning, we’re at our tallest. As we go about our day, gravity compresses the spinal discs and we lose about 1.5 cm (0.6 inches) in height. Then we sleep again, and the spine expands again. But in space, astronauts spines have been known to grow up to 7 cm. (2.75 in.)

Study leader David A. Green explains it: “On Earth your spine is compressed by gravity as you’re on your feet, then you go to bed at night and your spine unloads – it’s a normal cyclic process.”

In microgravity, the spine of an astronaut is never compressed by gravity, and stays unloaded. The resulting expansion causes pain. As Green says, “In space there’s no gravitational loading. Thus the discs in your spine may continue to swell, the natural curves of the spine may be reduced and the supporting ligaments and muscles — no longer required to resist gravity – may become loose and weak.”

The SkinSuit being developed by the Space Medicine Office of ESA’s European Astronaut Centre and the King’s College in London is based on work done by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). It’s a spandex-based garment that simulates gravity by squeezing the body from the shoulders to the feet.

The Skinsuits were tested on-board the International Space Station by ESA astronauts Andreas Mogensen and Thomas Pesquet. But they could only be worn for a short period of time. “The first concepts were really uncomfortable, providing some 80% equivalent gravity loading, and so could only be worn for a couple of hours,” said researcher Philip Carvil.

Back on Earth, the researchers worked on the suit to improve it. They used a waterbed half-filled with water rich in magnesium salts. This re-created the microgravity that astronauts face in space. The researchers were inspired by the Dead Sea, where the high salt content allows swimmers to float on the surface.

“During our longer trials we’ve seen similar increases in stature to those experienced in orbit, which suggests it is a valid representation of microgravity in terms of the effects on the spine,” explains researcher Philip Carvil.

Studies using students as test subjects have helped with the development of the SkinSuit. After lying on the microgravity-simulating waterbed both with and without the SkinSuit, subjects were scanned with MRI’s to test the SkinSuit’s effectiveness. The suit has gone through several design revisions to make it more comfortable, wearable, and effective. It’s now up to the Mark VI design.

“The Mark VI Skinsuit is extremely comfortable, to the point where it can be worn unobtrusively for long periods of normal activity or while sleeping,” say Carvil. “The Mk VI provides around 20% loading – slightly more than lunar gravity, which is enough to bring back forces similar to those that the spine is used to having.”

“The results have yet to be published, but it does look like the Mk VI Skinsuit is effective in mitigating spine lengthening,” says Philip. “In addition we’re learning more about the fundamental physiological processes involved, and the importance of reloading the spine for everyone.”

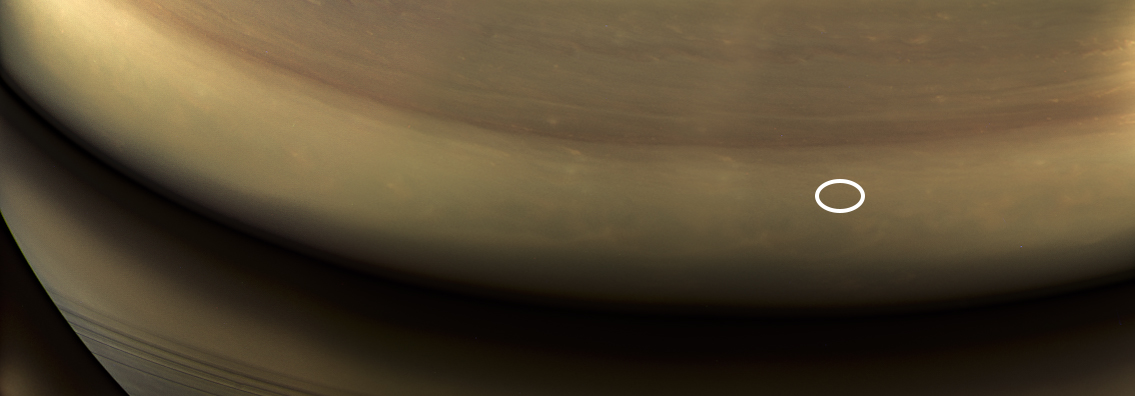

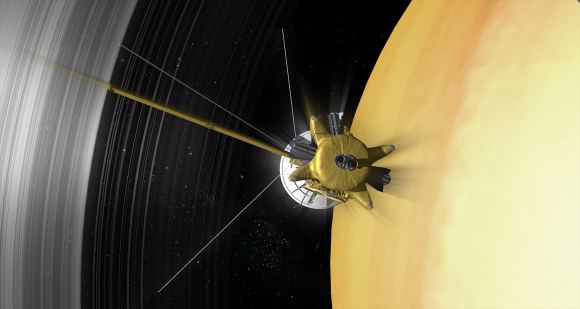

On September 15th, 2017, after nearly 20 years in service, the Cassini spacecraft ended its mission by plunging into the atmosphere of Saturn. During the 13 years it spent in the Saturn system, this probe revealed a great deal about the gas giant, its rings, and its systems of moons. As such, it was a bittersweet moment for the mission team when the probe concluded its Grand Finale and began descending into Saturn’s atmosphere.

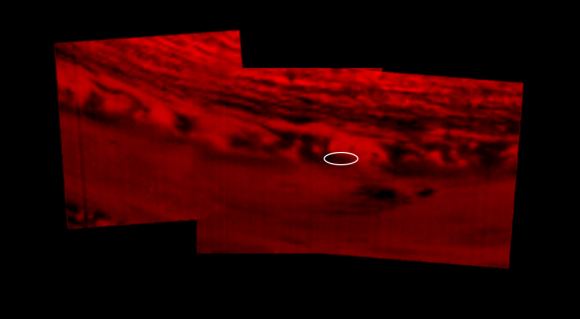

Even though the mission has concluded, scientists are still busy poring over the data sent back by the probe. These include a mosaic of the final images snapped by Cassini’s cameras, which show the location of where it would enter Saturn’s atmosphere just hours later. The exact spot (shown above) is indicated by a white oval, which was on Saturn’s night side at the time, but would later come around to be facing the Sun.

From the beginning, the Cassini mission was a game-changer. After reaching the Saturn system on July 1st, 2004, the probe began a series of orbits around Saturn that allowed it conduct close flybys of several of its moons. Foremost among these were Saturn’s largest moon Titan and its icy moon Enceladus, both of which proved to be a treasure trove of scientific data.

On Titan, Cassini revealed evidence of methane lakes and seas, the existence of a methanogenic cycle (similar to Earth’s hydrological cycle), and the presence of organic molecules and prebiotic chemistry. On Enceladus, Cassini examined the mysterious plumes emanating from its southern pole, revealing that they extended all the way to the moon’s interior ocean and contained organic molecules and hydrated minerals.

These findings have inspired a number of proposals for future robotic missions to explore Titan and Enceladus more closely. So far, proposals range from exploring Titan’s surface and atmosphere using lightweight aerial platforms, balloons and landers, or a dual quadcopter. Other proposals include exploring its seas using a paddleboat or a even a submarine. And alongside Europa, there are scientists clamoring for a mission to Enceladus and other “Ocean Worlds” to explore its plumes and maybe even its interior ocean.

Beyond that, Cassini also revealed a great deal about Saturn’s atmosphere, which included the persistent hexagonal storm that exists around the planet’s north pole. During its Grand Finale, where it made 22 orbits between Saturn and its rings, the probe also revealed a great deal about the three-dimensional structure and dynamic behavior of the planet’s famous system of rings.

It is only fitting then that the Cassini probe would also capture images of the very spot where its mission would end. The images were taken by Cassini’s wide-angle camera on Sept. 14th, 2017, when the probe was at a distance of about 634,000 km (394,000 mi) from Saturn. They were taken using red, green and blue spectral filters, which were then combined to show the scene in near-natural color.

The resulting image is not dissimilar from another mosaic that was released on September 15th, 2017, to mark the end of the Cassini mission. This mosaic was created using data obtained by Cassini’s visual and infrared mapping spectrometer, which also showed the exact location where the spacecraft would enter the atmosphere – 9.4 degrees north latitude by 53 degrees west longitude.

The main difference, of course, is that this latest mosaic benefits from the addition of color, which provides a better sense of orientation. And for those who are missing the Cassini mission and its regular flow of scientific discoveries, its much more emotionally fitting! While we may never be able to find the wreckage buried inside Saturn’s atmosphere, it is good to know where its last known location was.

Further Reading: NASA

NASA’s Earth Observatory is a vital part of the space agency’s mission to advance our understanding of Earth, its climate, and the ways in which it is similar and different from the other Solar Planets. For decades, the EO has been monitoring Earth from space in order to map it’s surface, track it’s weather patterns, measure changes in our environment, and monitor major geological events.

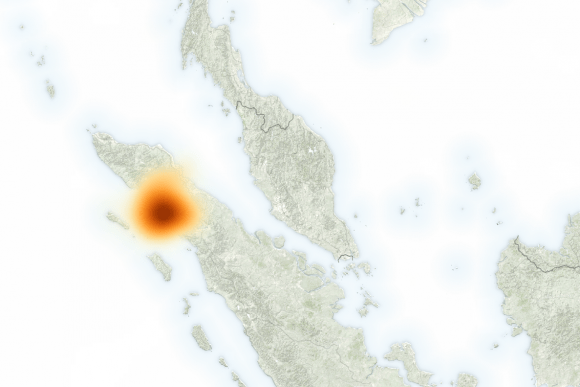

For instance, Mount Sinabung – a stratovolcano located on the island of Sumatra in Indonesia – became sporadically active in 2010 after centuries of being dormant. But on February 19th, 2018, it erupted violently, spewing ash at least 5 to 7 kilometers (16,000 to 23,000 feet) into the air over Indonesia. Just a few hours later, Terra and other NASA Earth Observatory satellites captured the eruption from orbit.

The images were taken with Terra’s Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS), which recorded a natural-color image of the eruption at 11:10 am local time (04:10 Universal Time). This was just hours after the eruption began and managed to illustrate what was being reported by sources on the ground. According to multiple reports from the Associated Press, the scene was one of carnage.

According to eye-witness accounts, the erupting lava dome obliterated a chunk of the peak as it erupted. This was followed by plumes of hot gas and ash riding down the volcano’s summit and spreading out in a 5-kilometer (3 mile) diameter. Ash falls were widespread, covering entire villages in the area and leading to airline pilots being issued the highest of alerts for the region.

In fact, ash falls were recorded as far as away as the town of Lhokseumawe – located some 260 km (160 mi) to the north. To address the threat to public health, the Indonesian government advised people to stay indoors due to poor air quality, and officials were dispatched to Sumatra to hand out face masks. Due to its composition and its particulate nature, volcanic ash is a severe health hazard.

On the one hand, it contains sulfur dioxide (SO²), which can irritate the human nose and throat when inhaled. The gas also reacts with water vapor in the atmosphere to produce acid rain, causing damage to vegetation and drinking water. It can also react with other gases in the atmosphere to form aerosol particles that can create thick hazes and even lead to global cooling.

These levels were recorded by the Suomi-NPP satellite using its Ozone Mapper Profiler Suite (OMPS). The image below shows what SO² concentrations were like at 1:20 p.m. local time (06:20 Universal Time) on February 19th, several hours after the eruption. The maximum concentrations of SO² reached 140 Dobson Units in the immediate vicinity of the mountain.

Erik Klemetti, a volcanologist, was on hand to witness the event. As he explained in an article for Discovery Magazine:

“On February 19, 2018, the volcano decided to change its tune and unleashed a massive explosion that potentially reached at least 23,000 and possibly to up 55,000 feet (~16.5 kilometers), making it the largest eruption since the volcano became active again in 2013.”

Klemetti also cited a report that was recently filed by the Darwin Volcanic Ash Advisory Center – part of the Australian Government’s Bureau of Meteorology. According to this report, the ash will drift to the west and fall into the Indian Ocean, rather than continuing to rain down on Sumatra. Other sensors on NASA satellites have also been monitoring Mount Sinabung since its erupted.

This includes the Cloud-Aerosol Lidar and Infrared Pathfinder Satellite Observation (CALIPSO), an environmental satellite operated jointly by NASA and France’s Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales (CNES). Data from this satellite indicated that some debris and gas released by the eruption has risen as high as 15 to 18 km (mi) into the atmosphere.

In addition, data from the Aura satellite‘s Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI) recently indicated rising levels of SO² around Sinabung, which could mean that fresh magma is approaching the surface. As i concluded:

“This could just be a one-off blast from the volcano and it will return to its previous level of activity, but it is startling to say the least. Sinabung is still a massive humanitarian crisis, with tens of thousands of people unable to return to their homes for years. Some towns have even been rebuilt further from the volcano as it has shown no signs of ending this eruptive period.”

Be sure to check out this video of the eruption, courtesy of New Zealand Volcanologist Dr. Janine Krippner:

Further Reading: NASA Earth Observatory

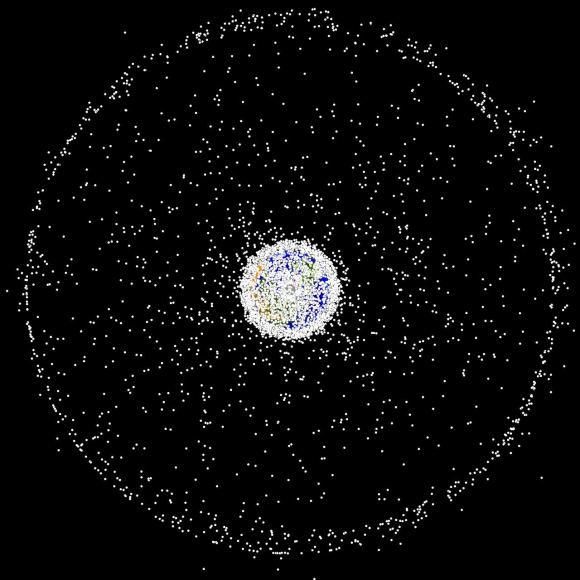

After sixty years of space agencies sending rockets, satellites and other missions into orbit, space debris has become something of a growing concern. Not only are there large pieces of junk that could take out a spacecraft in a single hit, but there are also countless tiny pieces of debris traveling at very high speeds. This debris poses a serious threat to the International Space Station (ISS), active satellites and future crewed missions in orbit.

For this reason, the European Space Agency is looking to develop better debris shielding for the ISS and future generations of spacecraft. This project, which is supported through the ESA’s General Support Technology Programme, recently conducted ballistics tests that looked at the efficiency of new fiber metal laminates (FMLs), which may replace aluminum shielding in the coming years.

To break it down, any and all orbital missions – be they satellites or space stations – need to be prepared for the risk of high-speed collisions with tiny objects. This includes the possibility of colliding with human-made space junk, but also includes the risk of micro-meteoroid object damage (MMOD). These are especially threatening during intense seasonal meteoroid streams, such as the Leonids.

While larger pieces of orbital debris – ranging from 5 cm (2 inches) to 1 meter (1.09 yards) in diameter – are regularly monitored by NASA and and the ESA’s Space Debris Office, the smaller pieces are undetectable – which makes them especially threatening. To make matters worse, collisions between bits of debris can cause more to form, a phenomena known as the Kessler Effect.

And since humanity’s presence Near-Earth Orbit (NEO) is only increasing, with thousands of satellites, space habitats and crewed missions planned for the coming decades, growing levels of orbital debris therefore pose an increasing risk. As engineer Andreas Tesch explained:

“Such debris can be very damaging because of their high impact speeds of multiple kilometres per second. Larger pieces of debris can at least be tracked so that large spacecraft such as the International Space Station can move out of the way, but pieces smaller than 1 cm are hard to spot using radar – and smaller satellites have in general fewer opportunities to avoid collision.”

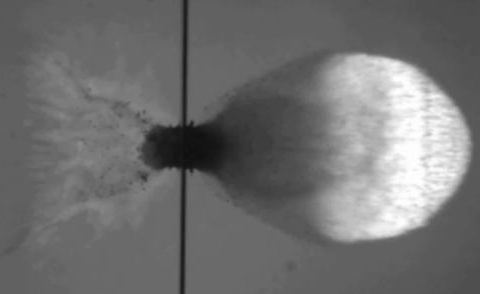

To see how their new shielding would hold up to space debris, a team of ESA researchers recently conducted a test where a 2.8 mm-diameter aluminum bullet was fired at sample of spacecraft shield – the results of which were filmed by a high-speed camera. At this size, and with a speed of 7 km/s, the bullet effectively simulated the impact energy that a small piece of debris would have as if it came into contact with the ISS.

As researcher Benoit Bonvoisin explained in a recent ESA press release:

“We used a gas gun at Germany’s Fraunhofer Institute for High-Speed Dynamics to test a novel material being considered for shielding spacecraft against space debris. Our project has been looking into various kinds of ‘fibre metal laminates’ produced for us by GTM Structures, which are several thin metal layers bonded together with composite material.”

As you can see from the video (posted above), the solid aluminum bullet penetrated the shield but then broke apart into a could of fragments and vapor, which are much easier for the next layer of armor to capture or deflect. This is standard practice when dealing with space debris and MMOD, where multiple shields are layered together to adsorb and capture the impact so that it doesn’t penetrate the hull.

An common variant of this is known as the ‘Whipple shield’, which was originally devised to guard against comet dust. This shielding consists of two layers, a bumper and a rear wall, with a mutual distance of 10 to 30 cm (3.93 to 11.8 inches). In this case, the FML, which is produced for the ESA by GTM Structures BV (a Netherlands-based aerospace company), consists of several thin metal layers bonded together with a composite material.

Based on this latest test, the FML appears to be well-suited at preventing damage to the ISS and future space stations. As Benoit indicated, he and his colleagues now need to test this shielding on other types of orbital missions. “The next step would be to perform in-orbit demonstration in a CubeSat, to assess the efficiency of these FMLs in the orbital environment,” he said.

And be sure to enjoy this video from the ESA’s Orbital Debris Office:

Further Reading: ESA

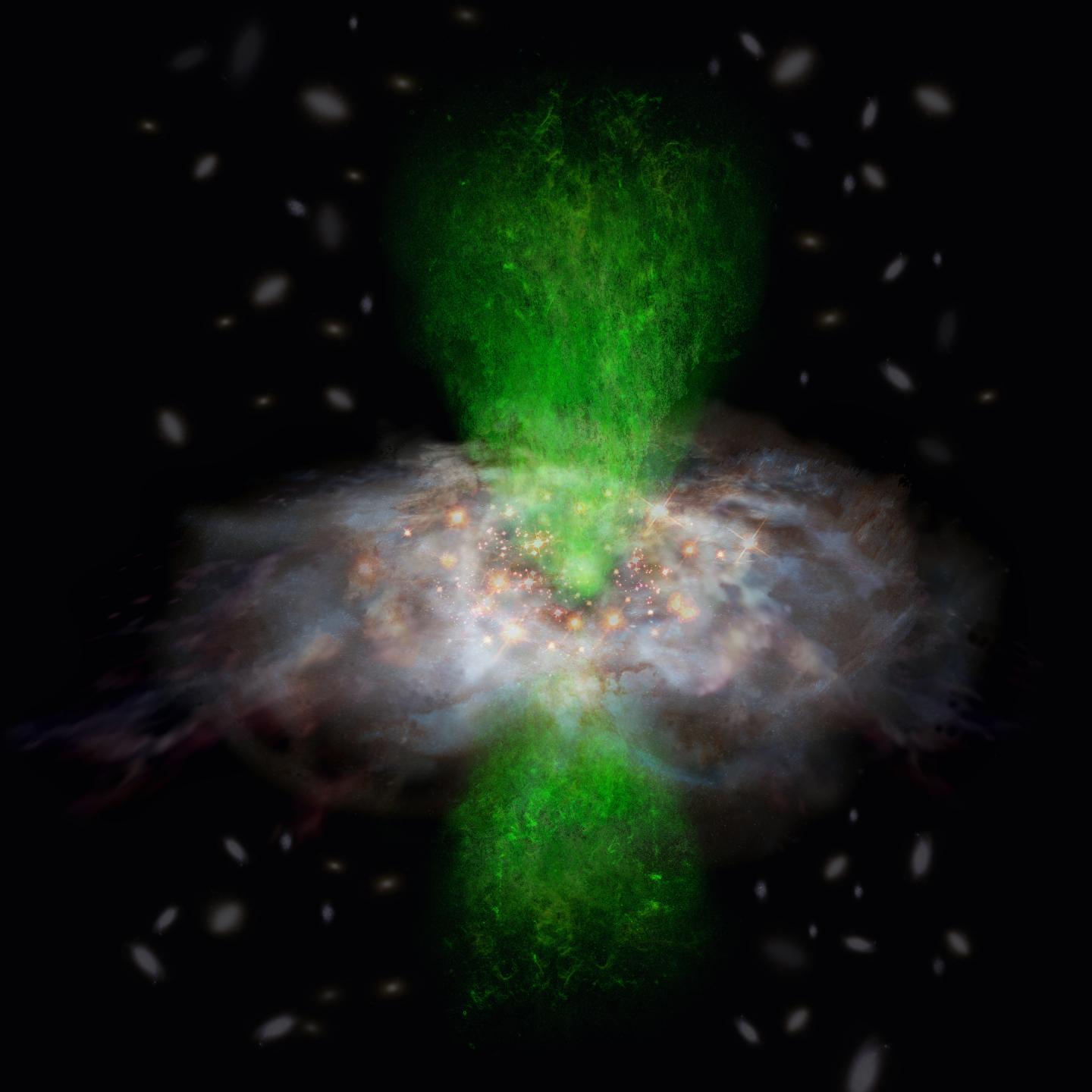

For decades, astrophysicists have puzzled over the relationship between Supermassive Black Holes (SMBHs) and their respective galaxies. Since the 1970s, it has been understood the majority of massive galaxies have an SMBH at their center, and that these are surrounded by rotating tori of gas and dust. The presence of these black holes and tori are what cause massive galaxies to have an Active Galactic Nucleus (AGN).

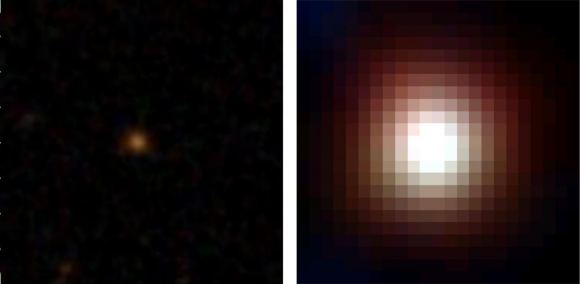

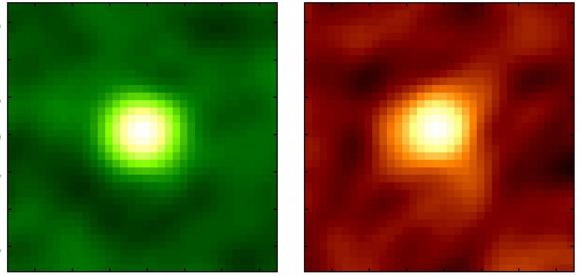

However, a recent study conducted by an international team of researchers revealed a startling conclusion when studying this relationship. Using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) to observe an active galaxy with a strong ionized gas outflow from the galactic center, the team obtained results that could indicate that there is no relationship between a an SMBH and its host galaxy.

The study, titled “No sign of strong molecular gas outflow in an infrared-bright dust-obscured galaxy with strong ionized-gas outflow“, recently appeared in the Astrophysical Journal. The study was led by Yoshiki Toba of the Academia Sinica Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics in Taiwan and included members from Ehime University, Kogakuin University, and the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, The Graduate University for Advanced Studies (SOKENDAI), and Johns Hopkins University.

The question of how SMBHs have affected galactic evolution remains one of the greatest unresolved questions in modern astronomy. Among astrophysicists, it is something of a foregone conclusion that SMBHs have a significant impact on the formation and evolution of galaxies. According to this accepted notion, SMBHs significantly influence the molecular gas in galaxies, which has a profound effect on star formation.

Basically, this theory holds that larger galaxies accumulate more gas, thus resulting in more stars and a more massive central black hole. At the same time, there is a feedback mechanism, where growing black holes accrete more matter on themselves. This results in them sending out a tremendous amount of energy in the form of radiation and particle jets, which is believed to curtail star formation in their vicinity.

However, when observing an infrared (IR)-bright dust-obscured galaxy (DOG) – WISE1029+0501 – Yoshiki and his colleagues obtained results that contradicted this notion. After conducting a detailed analysis using ALMA, the team found that there were no signs of significant molecular gas outflow coming from WISE1029+0501. They also found that star-forming activity in the galaxy was neither more intense or suppressed.

This indicates that a strong ionized gas outflow coming from the SMBH in WISE1029+0501 did not significantly affect the surrounding molecular gas or star formation. As Dr. Yoshiki Toba explained, this result:

“[H]as made the co-evolution of galaxies and supermassive black holes more puzzling. The next step is looking into more data of this kind of galaxies. That is crucial for understanding the full picture of the formation and evolution of galaxies and supermassive black holes”.

This not only flies in the face of conventional wisdom, but also in the face of recent studies that showed a tight correlation between the mass of central black holes and those of their host galaxies. This correlation suggests that supermassive black holes and their host galaxies evolved together over the course of the past 13.8 billion years and closely interacted as they grew.

In this respect, this latest study has only deepened the mystery of the relationship between SMBHs and their galaxies. As Tohru Nagao, a Professor at Ehime University and a co-author on the study, indicated:

“[W]e astronomers do not understand the real relation between the activity of supermassive black holes and star formation in galaxies. Therefore, many astronomers including us are eager to observe the real scene of the interaction between the nuclear outflow and the star-forming activities, for revealing the mystery of the co-evolution.”

The team selected WISE1029+0501 for their study because astronomers believe that DOGs harbor actively growing SMBHs in their nuclei. In particular, WISE1029+0501 is an extreme example of galaxies where outflowing gas is being ionized by the intense radiation from its SMBH. As such, researchers have been highly motivated to see what happens to this galaxy’s molecular gas.

The study was made possible thanks to ALMA’s sensitivity, which is excellent when it comes to investigating the properties of molecular gas and star-forming activity in galaxies. In fact, multiple studies have been conducted in recent years that have relied on ALMA to investigate the gas properties and SMBHs of distant galaxies.

And while the results of this study contradict widely-held theories about galactic evolution, Yoshiki and his colleagues are excited about what this study could reveal. In the end, it may be that radiation from a SMBH does not always affect the molecular gas and star formation of its host galaxy.

“[U]nderstanding such co-evolution is crucial for astronomy,” said Yoshiki. “By collecting statistical data of this kind of galaxies and continuing in more follow-up observations using ALMA, we hope to reveal the truth.”

Further Reading: ALMA Observatory, Astrophysical Journal