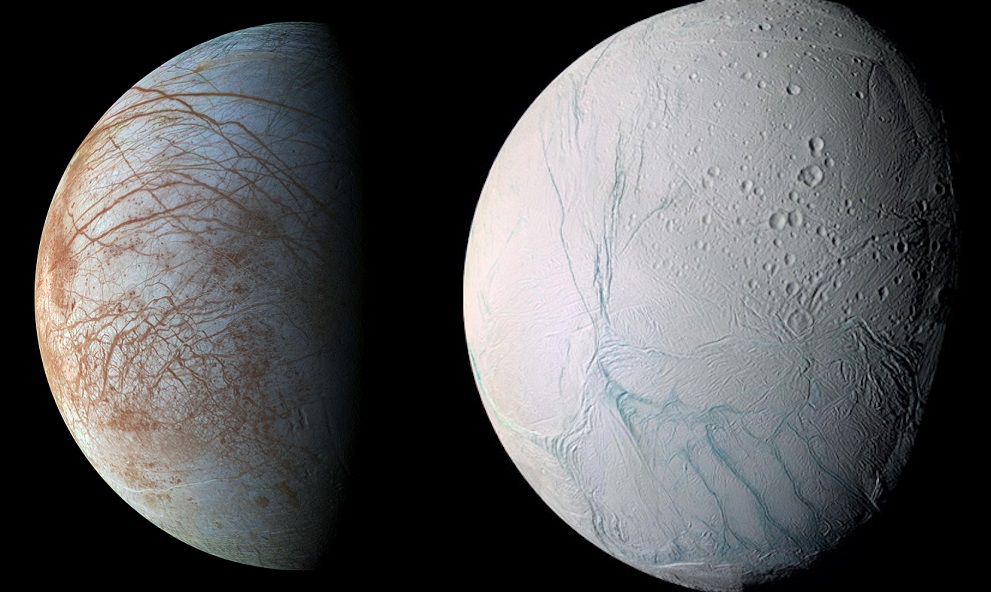

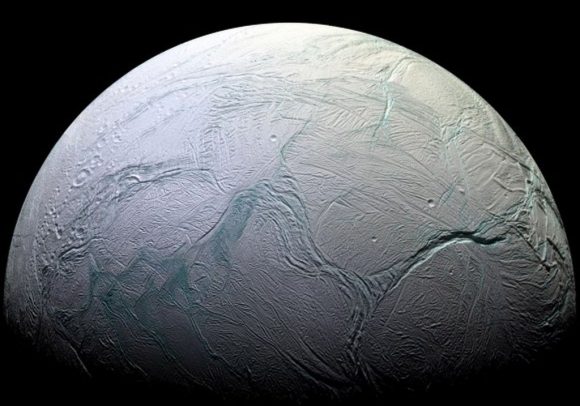

Some truly interesting and ambitious missions have been proposed by NASA and other space agencies for the coming decades. Of these, perhaps the most ambitious include missions to explore the “Ocean Worlds” of the Solar System. Within these bodies, which include Jupiter’s moon Europa and Saturn’s moon Enceladus, scientists have theorized that life could exist in warm-water interior oceans.

By the 2020s and 2030s, robotic missions are expected to reach these worlds and set down on them, sampling ice and exploring their plumes for signs of biomarkers. But according to a new study by an international team of scientists, the surfaces of these moons may have extremely low-density surfaces. In other words, the surface ice of Europa and Enceladus could be too soft to land on.

The study, titled “Laboratory simulations of planetary surfaces: Understanding regolith physical properties from remote photopolarimetric observations“, was recently published in the scientific journal Icarus. The study was led by Robert M.Nelson, the Senior Scientist at the Planetary Science Institute (PSI) and included members from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the California Polytechnic State University at Pomona, and multiple universities.

For the sake of their study, the team sought to explain the unusual negative polarization behavior at low phase angles that has been observed for decades when studying atmosphereless bodies. This polarization behavior is thought to be the result of extremely fine-grained bright particles. To simulate these surfaces, the team used thirteen samples of aluminum oxide powder (Al²O³).

Aluminum oxide is considered to be an excellent analog for regolith found on high aldebo Airless Solar System Bodies (ASSB), which include Europa and Encedalus as well as eucritic asteroids like 44 Nysa and 64 Angelina. The team then subjected these samples to photopolarimetric examinations using the goniometric photopolarimeter at Mt. San Antonio College.

What they found was that the bright grains that make up the surfaces of Europa and Enceladus would measure about a fraction of a micron and have a void space of about 95%. This corresponds to material that is less dense than freshly-fallen snow, which would seem to indicate that these moon’s have very soft surfaces. Naturally, this does not bode well for any missions that would attempt to set down on Europa or Enceladus’ surface.

But as Nelson explained in PSI press release, this is not necessarily bad news, and such fears have been raised before:

“Of course, before the landing of the Luna 2 robotic spacecraft in 1959, there was concern that the Moon might be covered in low density dust into which any future astronauts might sink. However, we must keep in mind that remote visible-wavelength observations of objects like Europa are only probing the outermost microns of the surface.”

So while Europa and Enceladus may have surfaces with a layer of low-density ice particles, it does not rule out that their outer shells are solid. In the end, landers may be forced to contend with nothing more than a thin sheet of snow when setting down on these worlds. What’s more, if these particles are the result of plume activity or action between the interior and the surface, they could hold the very biomarkers the probes are looking for.

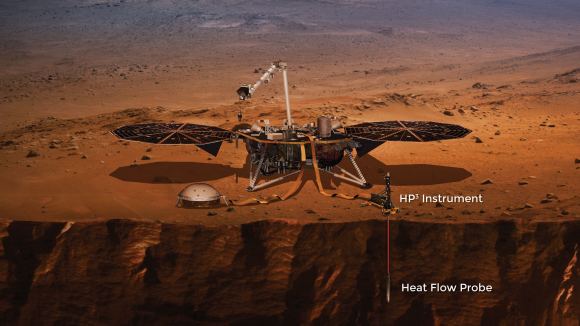

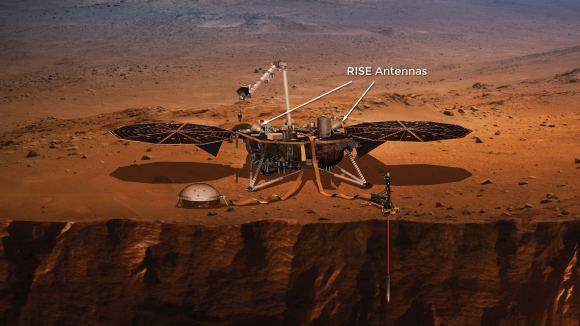

Of course, further studies are needed before any robotic landers are sent to bodies like Europa and Enceladus. In the coming years, the James Webb Space Telescope will be conducting studies of these and other moons during its first five months in service. This will include producing maps of the Galilean Moons, revealing things about their thermal and atmospheric structure, and searching their surfaces for signs of plumes.

The data the JWST obtains with its advanced suite of spectroscopic and near-infrared instruments will also provide additional constraints on their surface conditions. And with other missions like the ESA’s proposed Europa Clipper conducting flybys of these moons, there’s no shortage to what we can learn from them.

Beyond being significant to any future missions to ASSBs, the results of this study are also likely to be of value when it comes to the field of terrestrial geo-engineering. Essentially, scientists have suggested that anthropogenic climate change could be mitigated by introducing aluminum oxide into the atmosphere, thus offsetting the radiation absorbed by greenhouse gas emissions in the upper atmosphere. By examining the properties of these grains, this study could help inform future attempts to mitigate climate change.

This study was made possible thanks in part to a contract provided by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory to the PSI. This contract was issued in support of the NASA Cassini Saturn Orbiter Visual and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer instrument team.

Further Reading: Planetary Science Institute, Icarus