Researchers at Canada’s McGill University have shown for the first time how existing technology could be used to directly detect life on Mars and other planets. The team conducted tests in Canada’s high arctic, which is a close analog to Martian conditions. They showed how low-weight, low-cost, low-energy instruments could detect and sequence alien micro-organisms. They presented their results in the journal Frontiers in Microbiology.

Getting samples back to a lab to test is a time consuming process here on Earth. Add in the difficulty of returning samples from Mars, or from Ganymede or other worlds in our Solar System, and the search for life looks like a daunting task. But the search for life elsewhere in our Solar System is a major goal of today’s space science. The team at McGill wanted to show that, conceptually at least, samples could be tested, sequenced, and grown in-situ at Mars or other locations. And it looks like they’ve succeeded.

Recent and current missions to Mars have studied the suitability of Mars for life. But they don’t have the ability to look for life itself. The last time a Mars mission was designed to directly search for life was in the 1970’s, when NASA’s Viking 1 and 2 missions landed on the surface. No life was detected, but decades later people still debate the results of those missions.

![The Viking 2 lander captured this image of itself on the Martian surface. The Viking Landers were the last missions to directly look for life on Mars. By NASA - NASA website; description,[1] high resolution image.[2], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17624](https://www.universetoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/608px-Viking2lander1-580x458.jpg)

But Mars is heating up, figuratively speaking, and the sophistication of missions to Mars keeps growing. With crewed missions to Mars a likely reality in the not-too-distant future, the team at McGill is looking ahead to develop tools to search for life there. And they focused on miniature, economical, low-energy technology. Much of the current technology is too large or demanding to be useful on missions to Mars, or to places like Enceladus or Europa, both future destinations in the Search for Life.

“To date, these instruments remain high mass, large in size, and have high energy requirements. Such instruments are entirely unsuited for missions to locations such as Europa or Enceladus for which lander packages are likely to be tightly constrained.”

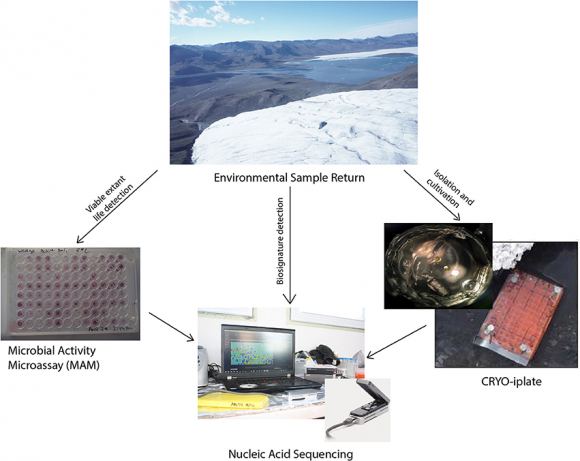

The team of researchers from McGill, which includes Professor Lyle Whyte and Dr. Jacqueline Goordial, have developed what they are calling the ‘Life Detection Platform (LDP).’ The platform is modular, so that different instruments can be swapped out depending on mission requirements, or as better instruments are developed. As it stands, the Life Detection Platform can culture microorganisms from soil samples, assess microbial activity, and sequence DNA and RNA.

There are already instruments available that can do what the LDP can do, but they’re bulky and require more energy to operate. They aren’t suitable for missions to far-flung destinations like Enceladus or Europa, where sub-surface oceans might harbour life. As the authors say in their study, “To date, these instruments remain high mass, large in size, and have high energy requirements. Such instruments are entirely unsuited for missions to locations such as Europa or Enceladus for which lander packages are likely to be tightly constrained.”

A key part of the system is a miniaturized, portable DNA sequencer called the Oxford Nanopore MiniON. The team of researchers behind this study were able to show for the first time that the MiniON can examine samples in extreme and remote environments. They also showed that when combined with other instruments it can detect active microbial life. The researches succeeded in isolatinh microbial extremophiles, detecting microbial activity, and sequencing the DNA. Very impressive indeed.

These are early days for the Life Detection Platform. The system required hands-on operation in these tests. But it does show proof of concept, an important stage in any technological development. “Humans were required to carry out much of the experimentation in this study, while life detection missions on other planets will need to be robotic,” says Dr Goordial.

“Humans were required to carry out much of the experimentation in this study, while life detection missions on other planets will need to be robotic.” – Dr. J. Goordial

The system as it stands now is useful here on Earth. The same things that allow it to search for and sequence microorganisms on other worlds make it suitable for the same task here on Earth. “The types of analyses performed by our platform are typically carried out in the laboratory, after shipping samples back from the field,” says Dr. Goordial. This makes the system desirable for studying epidemics in remote areas, or in rapidly changing conditions where transporting samples to distant labs can be problematic.

These are very exciting times in the Search for Life in our Solar System. If, or when, we discover microbial life on Mars, Europa, Enceladus, or some other world, it will likely be done robotically, using equipment similar to the LDP.