Between 2005 and 2017, the number of people who are digitally connected increased by a factor of three and a half. In other words, the number of people with internet access went from just over 1 billion to about 3.5, from about 15% to roughly half the world’s population. And in the coming decade, it is estimated that roughly 5 billion people – that’s 70% of the world’s population – will have internet access.

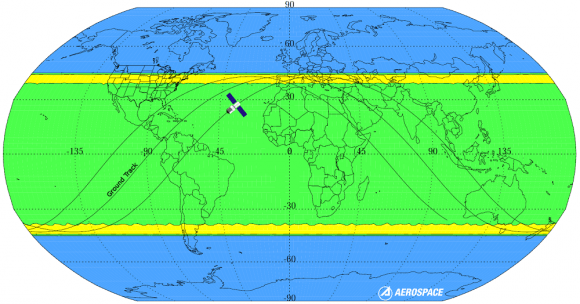

Much is this growth is powered by new ways of in which internet services are being provided, which in the coming years will include space-based internet. In 2018 alone, eight new constellations of internet satellites will begin deployment to Low-Earth Orbit (LEO) and Medium-Earth Orbit (MEO). Once operational, these constellations are expected to not only increas broadband access, but also demonstrate the soundness of the business model.

For instance, SpaceX will be launching a prototype internet satellite this year, the first of a planned constellation of 4,425 satellites that will make up its Starlink Service. As part of Elon Musk’s vision to bring internet access to the entire globe (one of many he’s had in recent years!), this constellation will be deployed to altitudes of 1,110 to 1,325 km (685-823 mi) – i.e. within LEO – by 2024.

Telecom and aerospace giants Samsung and Boeing are also sending internet satellites to orbit this year. In Samsung’s case, the plan is to begin deploying the first of 4,600 satellites to LEO by 2028. Once operational, this interconnected constellation will provide a 200-GB per month service in the V band for up to 5 billion users. Boeing has similar plans for a 2,956 constellation that will provide enhanced broadband (also in the V band).

The first part of this system will consist of 1,396 satellites deployed to an altitude of 1,200 km (746 mi) within the first six years. Others companies that are getting in on the ground floor of the space-based internet trend include OneWeb, Telesat LEO, SES O3B, Iridium Next and LeoSat. Each of them have plans to send between a few dozen and a few hundred satellites to LEO to enhance global bandwidth, starting this year.

Iridium, LeoSat, and SES O3B have all entered into partnerships with Thales Alenia Space, a leading designer of telecommunication and navigation satellites as well as orbital infrastructure. Thales’ resume also includes providing parts and services for the International Space Station, as well as playing major role in the development of the ATV cargo vessel, as part of the NASA/ESA Cygnus program.

In conjunction with Thales and Boeing, SES 03b plans to use its proposed constellation of 27 satellites to bridge the global digital divide. In the past, O3b was in the practice of providing cruise ships with wireless access. After merging with SES in 2016, they expanded their vision to include geosynchronous-Earth-oribit and MEO satellites. The company plans to have all its satellites operational by 2021.

Iridium is also partnering with Orbital ATK, the commercial aerospace company, to make their constellation happen. And whereas other companies are focused on providing enhanced bandwidth and access, Iridium’s main goal is to provide safety services for cockpit Wi-Fi. These services will be restricted to non-passenger flights for the time being, and will operate in the L and Ka bands.

And the there’s LeoSat’s plan to send up to 108 satellites to LEO which will be interconnected through laser links to provide what they describe as “an optical backbone in space about 1.5 times faster than terrestrial fiber backbones”. The first of these small, high-throughput satellites – which will deliver services in the Ka-band – is scheduled to launch in 2019.

Similarly, Telesat LEO hopes to create an internet satellite network to provide services that are comparable to fiber-optic internet connections. According to the company, their services will target “busy airports; military operations on land, sea and air; major shipping ports; large, remote communities; and other areas of concentrated demand.” The company plans to deploy two prototype satellites to LEO later this year, which were developed in conjunction with Airbus’ SSTL and Space Systems Loral.

With all the developments taking place these days, it does seem like the dream of a global internet (much like the Internet of Things (IoT) is fast becoming a reality. In the coming decades, we may look back at the late 20th and early 21st centuries the same way we look at the stone ages. Compared to a world where almost everyone has internet access and can download, upload, stream and surf, a world where only a few million people could do that will seem quite primitive!

Featured: Aviation Week, Popular Mechanics