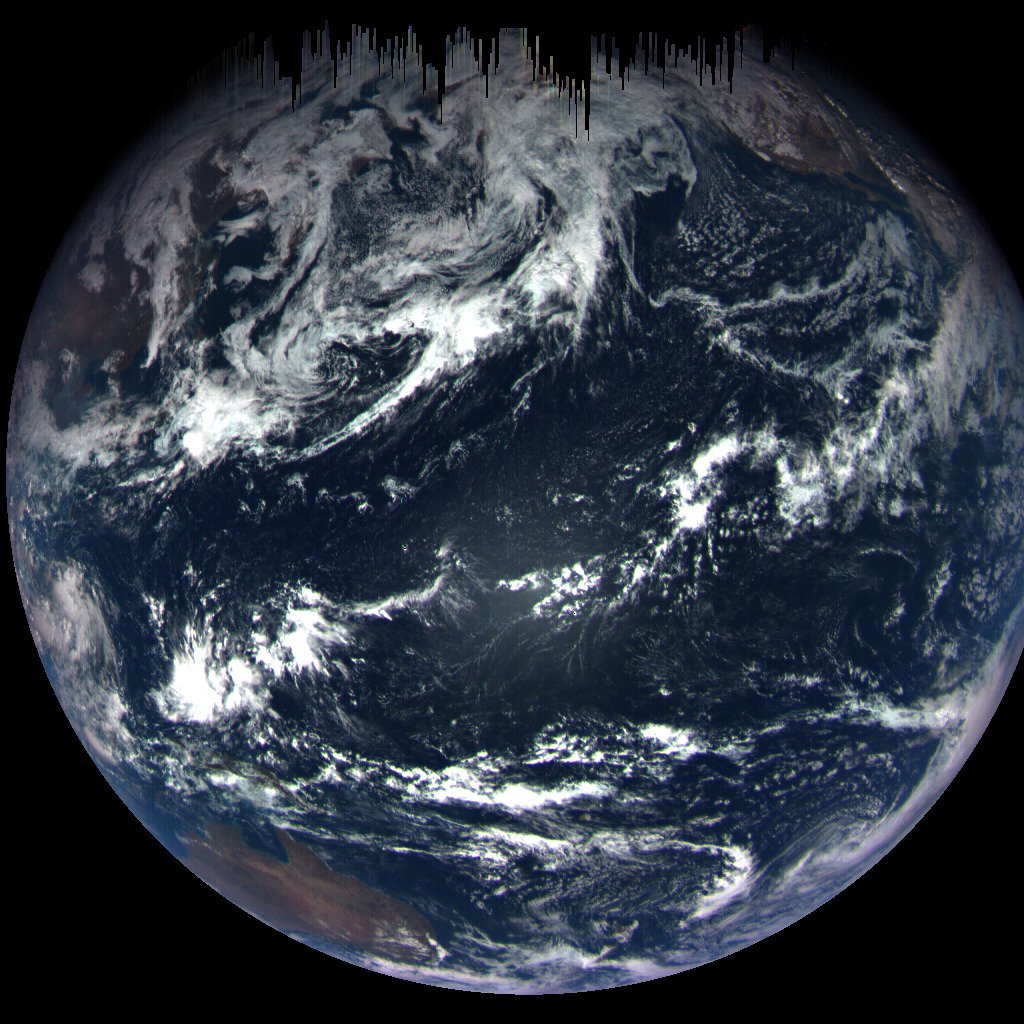

KENNEDY SPACE CENTER, FL – NASA’s OSIRIS-REx asteroid mission captured a lovely ‘Blue Marble’ image of our Home Planet during last Fridays (Sept. 22) successful gravity assist swing-by sending the probe hurtling towards asteroid Bennu for a rendezvous next August on a round trip journey to snatch pristine soil samples.

The newly released color composite image of Earth was taken on Sept. 22 by the spacecrafts MapCam camera.

It was taken at a range of approximately 106,000 miles (170,000 kilometers), just a few hours after OSIRIS-REx completed its critical Earth Gravity Assist (EGA) maneuver.

“NASA’s asteroid sample return spacecraft successfully used Earth’s gravity on Friday, Sept. 22 to slingshot itself on a path toward the asteroid Bennu, for a rendezvous next August,” the agency confirmed after receiving the eagerly awaited telemetry.

OSIRIS-Rex, which stands for Origins, Spectral Interpretation, Resource Identification, and Security – Regolith Explorer, is NASA’s first ever asteroid sample return mission.

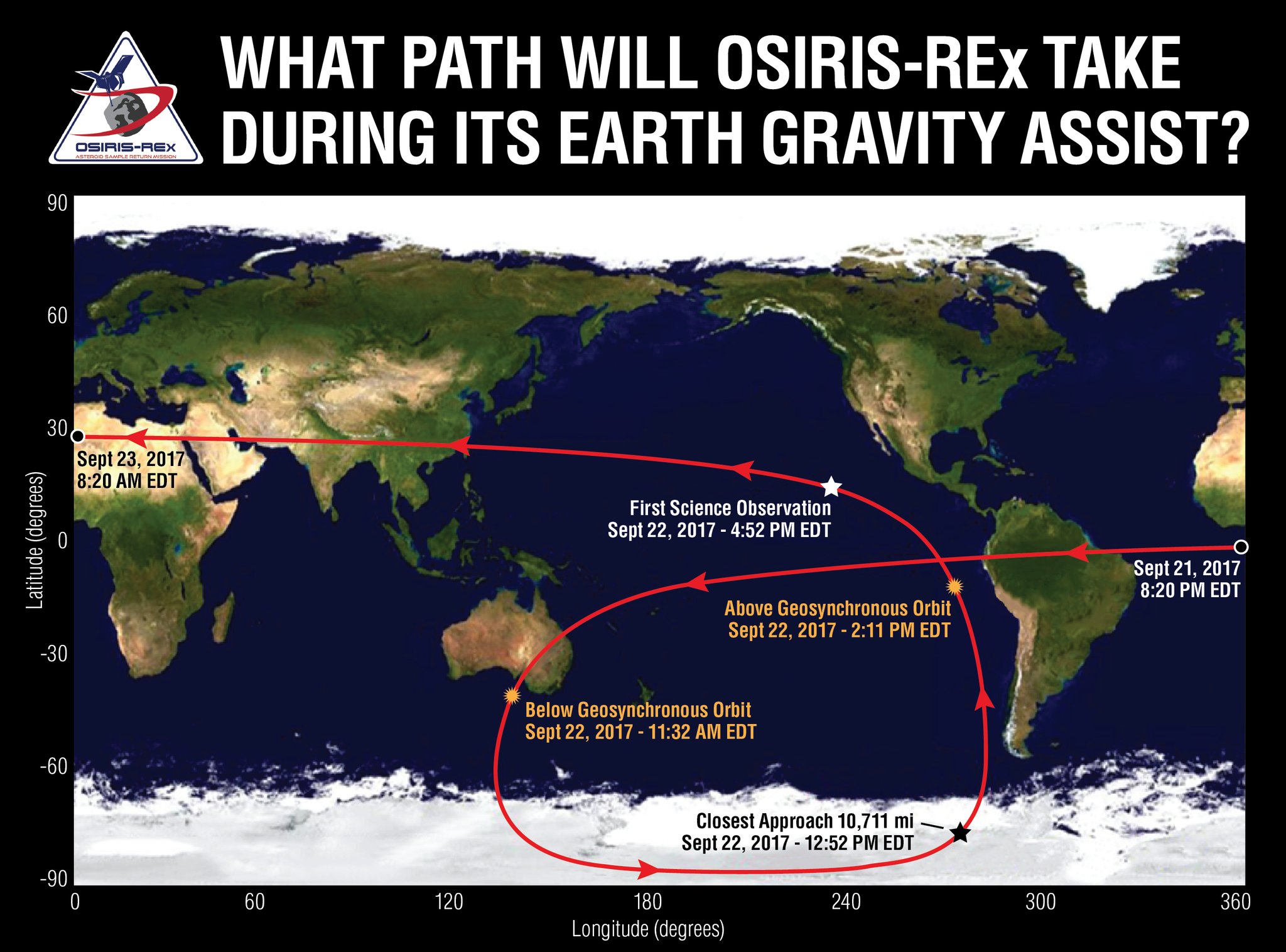

As it swung by Earth at 12:52 p.m. EDT on Sept. 22, OSIRIS-REx passed only 10,711 miles (17,237 km) above Antarctica, just south of Cape Horn, Chile.

The probe departed Earth by following a flight path that continued north over the Pacific Ocean and has already travelled 600 million miles (1 billion kilometers) since launching on Sept. 8, 2016.

The preplanned EGA maneuver provided the absolutely essential gravity assisted speed boost required for OSIRIS-Rex to gain enough velocity to complete its journey to the carbon rich asteroid Bennu and back.

The mission was only made possible by the slingshot which provided a velocity change to the spacecraft of 8,451 miles per hour (3.778 kilometers per second).

“The encounter with Earth is fundamental to our rendezvous with Bennu,” said Rich Burns, OSIRIS-REx project manager at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, in a statement.

“The total velocity change from Earth’s gravity far exceeds the total fuel load of the OSIRIS-REx propulsion system, so we are really leveraging our Earth flyby to make a massive change to the OSIRIS-REx trajectory, specifically changing the tilt of the orbit to match Bennu.”

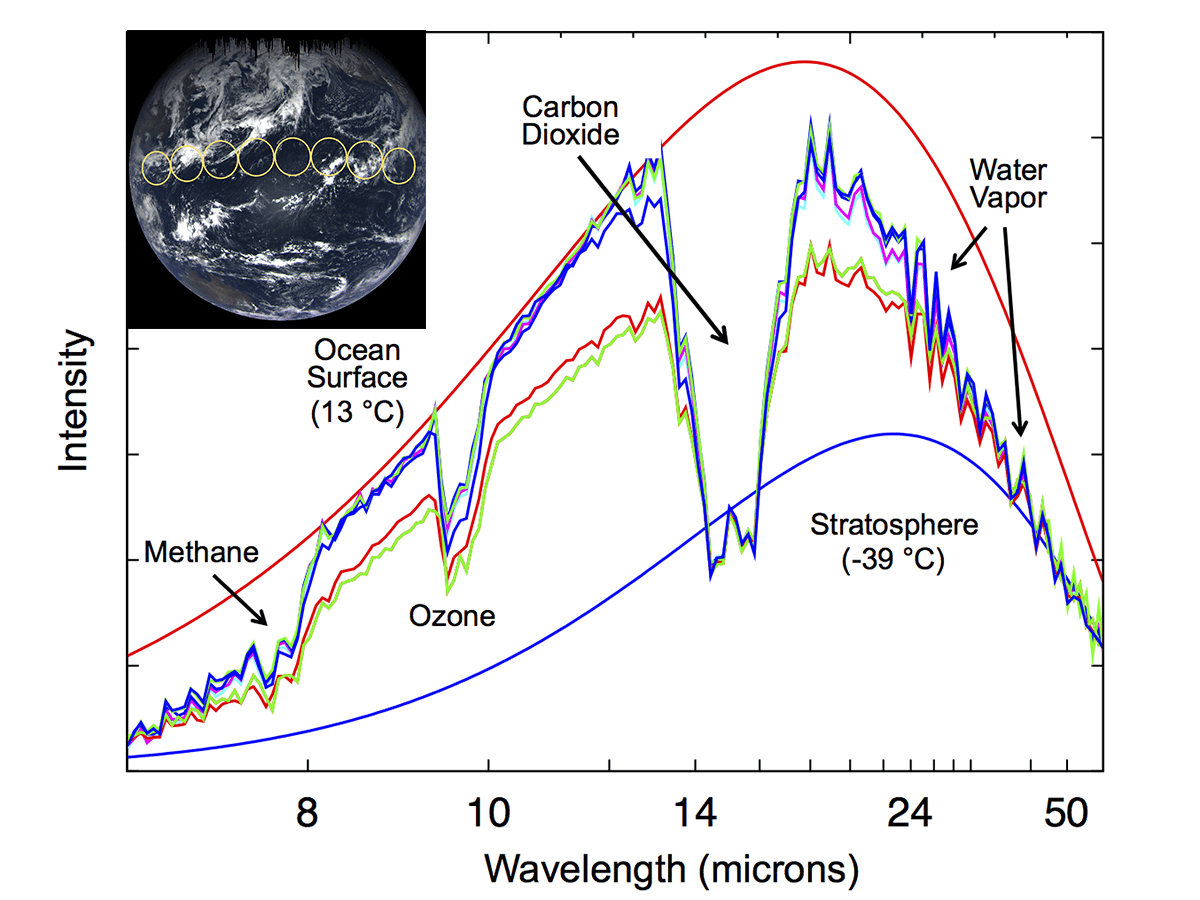

The spacecraft conducted a post flyby science campaign by collecting images and science observations of Earth and the Moon that began four hours after closest approach in order to test and calibrate its onboard suite of five science instruments and help prepare them for OSIRIS-REx’s arrival at Bennu in late 2018.

The MapCam camera Blue Marble image is the first one to be released by NASA and the science team.

The image is centered on the Pacific Ocean and shows several familiar landmasses, including Australia in the lower left, and Baja California and the southwestern United States in the upper right.

“The dark vertical streaks at the top of the image are caused by short exposure times (less than three milliseconds),” said the team.

“Short exposure times are required for imaging an object as bright as Earth, but are not anticipated for an object as dark as the asteroid Bennu, which the camera was designed to image.”

The instrument will gather additional data and measurements scanning the Earth and the Moon for three more days over the next two weeks.

“The opportunity to collect science data over the next two weeks provides the OSIRIS-REx mission team with an excellent opportunity to practice for operations at Bennu,” said Dante Lauretta, OSIRIS-REx principal investigator at the University of Arizona, Tucson.

“During the Earth flyby, the science and operations teams are co-located, performing daily activities together as they will during the asteroid encounter.”

The OSIRIS-Rex spacecraft originally departed Earth atop a United Launch Alliance Atlas V rocket under crystal clear skies on September 8, 2016 at 7:05 p.m. EDT from Space Launch Complex 41 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida.

Everything with the launch and flyby went exactly according to plan for the daring mission boldly seeking to gather rocks and soil from carbon rich Bennu.

OSIRIS-Rex is equipped with an ingenious robotic arm named TAGSAM designed to collect at least a 60-gram (2.1-ounce) sample and bring it back to Earth in 2023 for study by scientists using the world’s most advanced research instruments.

Watch for Ken’s continuing onsite NASA mission and launch reports direct from the Kennedy Space Center and Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida.

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Earth and Planetary science and human spaceflight news.

Ken Kremer