The Solar System is a beautiful thing to behold. Between its four terrestrial planets, four gas giants, multiple minor planets composed of ice and rock, and countless moons and smaller objects, there is simply no shortage of things to study and be captivated by. Add to that our Sun, an Asteroid Belt, the Kuiper Belt, and many comets, and you’ve got enough to keep your busy for the rest of your life.

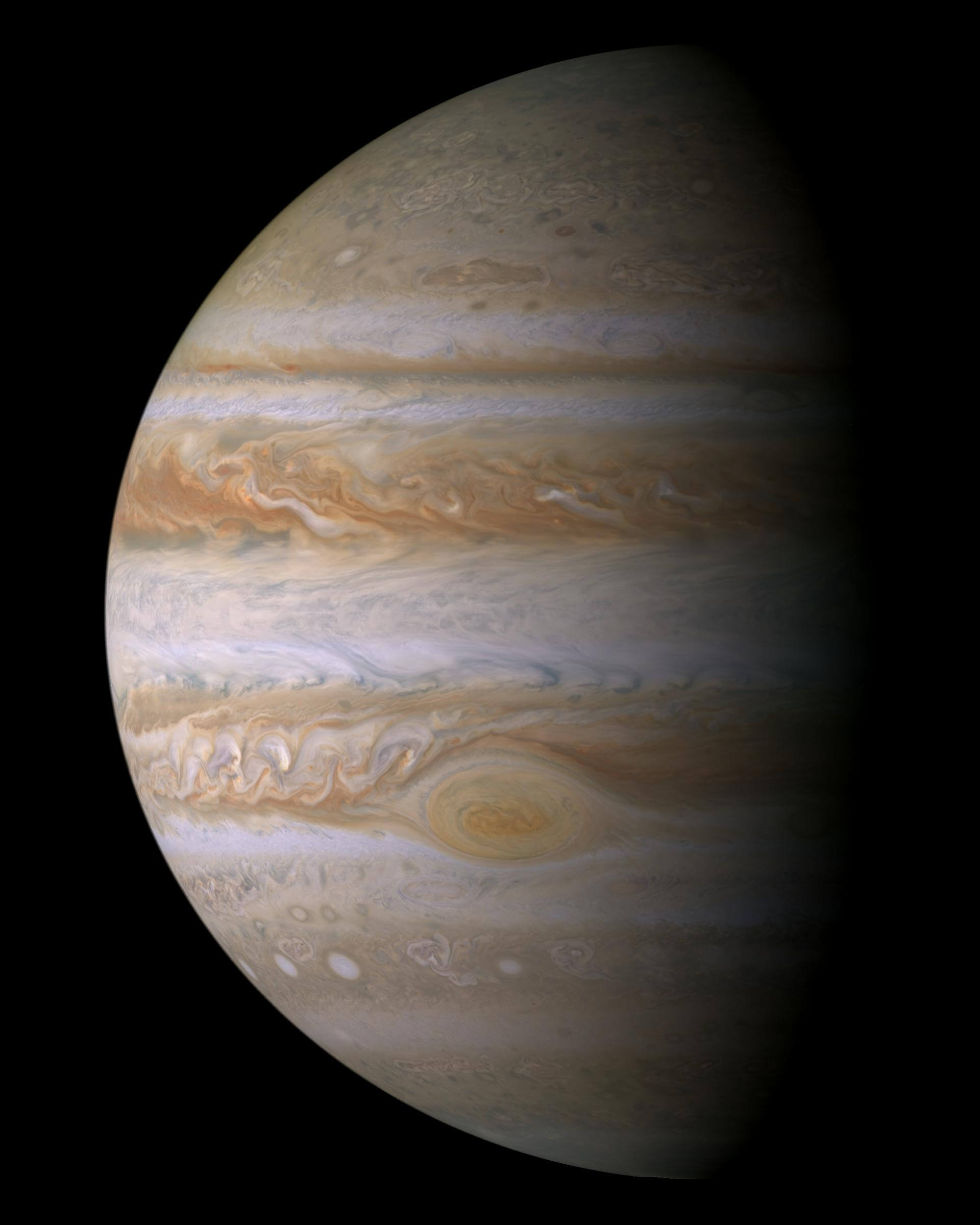

But why exactly is it that the larger bodies in the Solar System are round? Whether we are talking about moon like Titan, or the largest planet in the Solar System (Jupiter), large astronomical bodies seem to favor the shape of a sphere (though not a perfect one). The answer to this question has to do with how gravity works, not to mention how the Solar System came to be.

Formation:

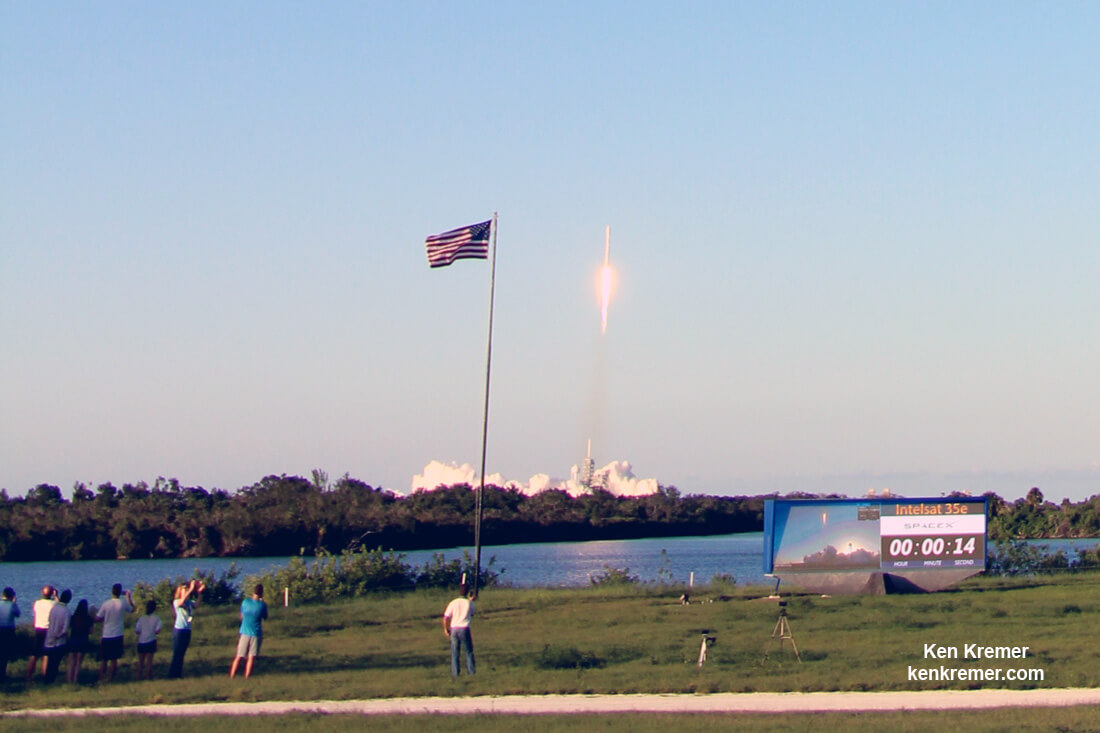

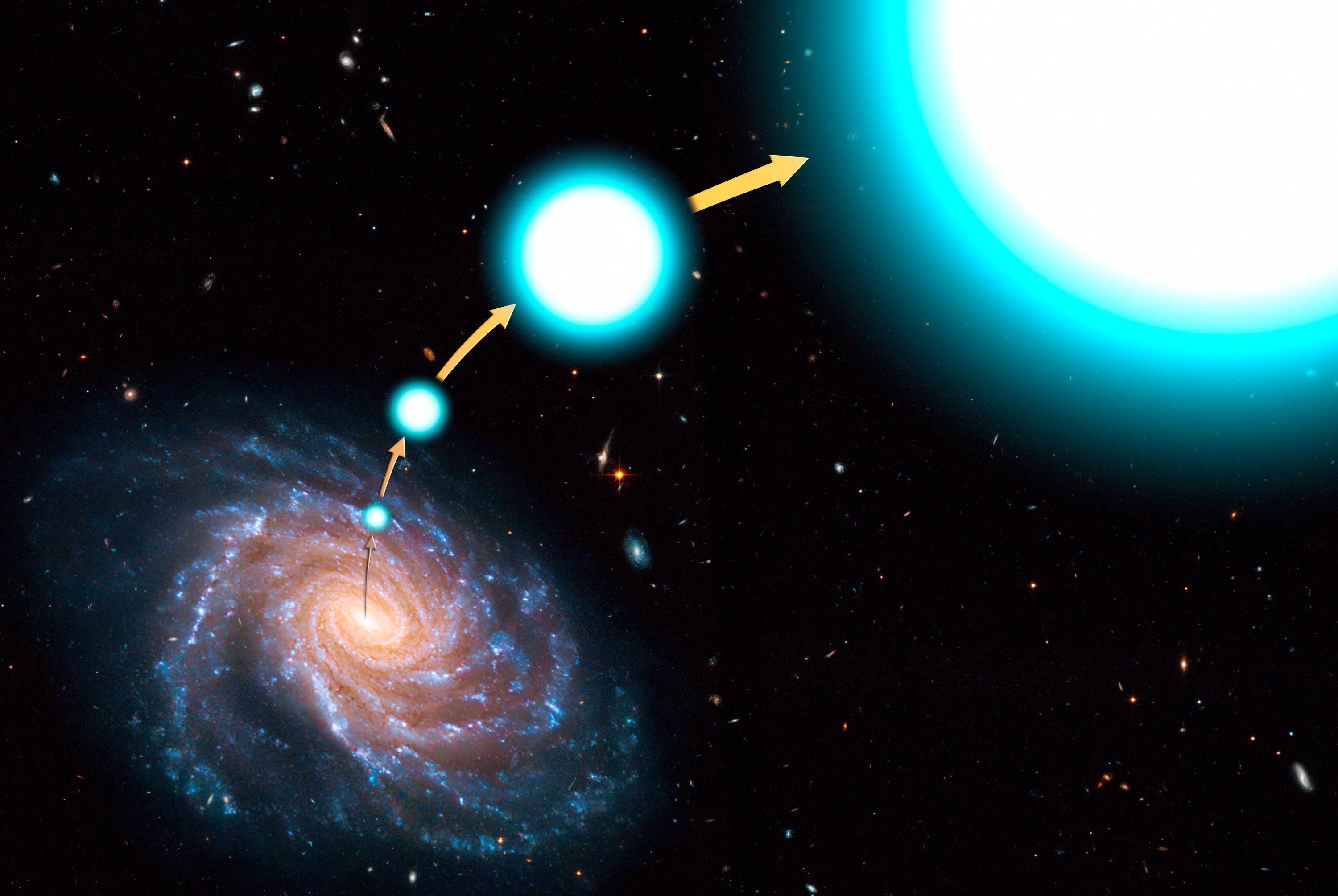

According to the most widely-accepted model of star and planet formation – aka. Nebular Hypothesis – our Solar System began as a cloud of swirling dust and gas (i.e. a nebula). According to this theory, about 4.57 billion years ago, something happened that caused the cloud to collapse. This could have been the result of a passing star, or shock waves from a supernova, but the end result was a gravitational collapse at the center of the cloud.

Due to this collapse, pockets of dust and gas began to collect into denser regions. As the denser regions pulled in more matter, conservation of momentum caused them to begin rotating while increasing pressure caused them to heat up. Most of the material ended up in a ball at the center to form the Sun while the rest of the matter flattened out into disk that circled around it – i.e. a protoplanetary disc.

The planets formed by accretion from this disc, in which dust and gas gravitated together and coalesced to form ever larger bodies. Due to their higher boiling points, only metals and silicates could exist in solid form closer to the Sun, and these would eventually form the terrestrial planets of Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars. Because metallic elements only comprised a very small fraction of the solar nebula, the terrestrial planets could not grow very large.

In contrast, the giant planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune) formed beyond the point between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter where material is cool enough for volatile icy compounds to remain solid (i.e. the Frost Line). The ices that formed these planets were more plentiful than the metals and silicates that formed the terrestrial inner planets, allowing them to grow massive enough to capture large atmospheres of hydrogen and helium.

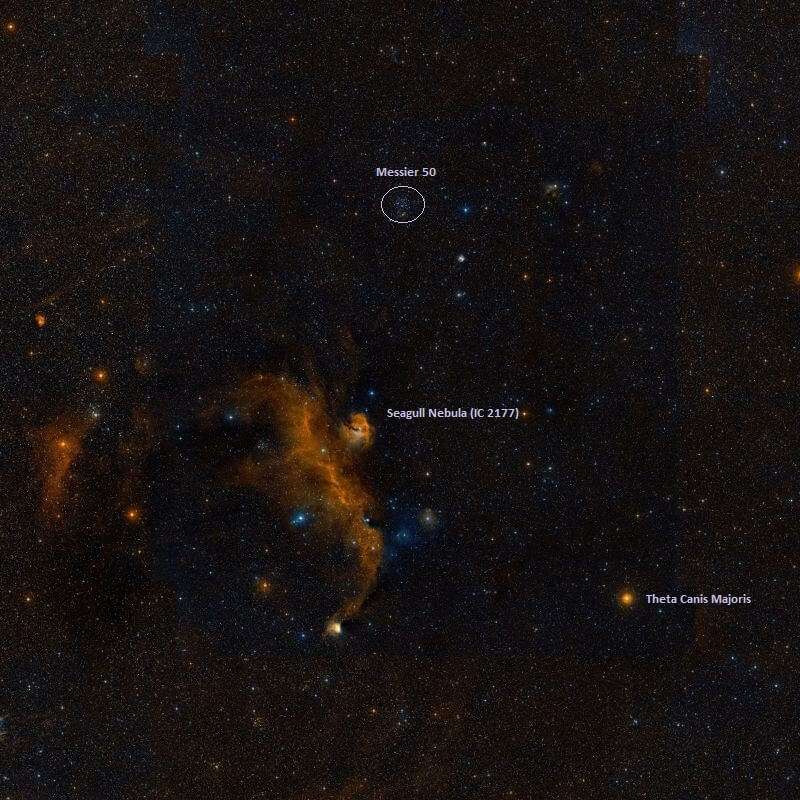

The leftover debris that never became planets congregated in regions such as the Asteroid Belt, the Kuiper Belt, and the Oort Cloud. So this is how and why the Solar System formed in the first place. Why is it that the larger objects formed as spheres instead of say, squares? The answer to this has to do with a concept known as hydrostatic equilibrium.

Hydrostatic Equilibrium:

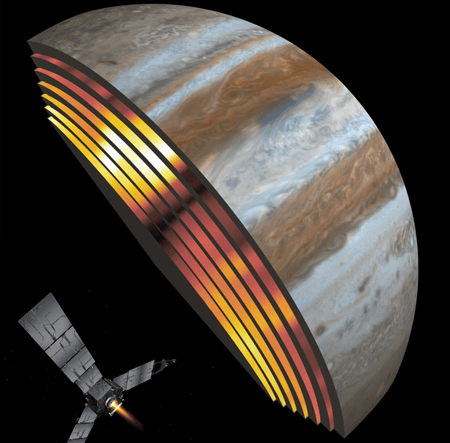

In astrophysical terms, hydrostatic equilibrium refers to the state where there is a balance between the outward thermal pressure from inside a planet and the weight of the material pressing inward. This state occurs once an object (a star, planet, or planetoid) becomes so massive that the force of gravity they exert causes them to collapse into the most efficient shape – a sphere.

Typically, objects reach this point once they exceed a diameter of 1,000 km (621 mi), though this depends on their density as well. This concept has also become an important factor in determining whether an astronomical object will be designated as a planet. This was based on the resolution adopted in 2006 by the 26th General Assembly for the International Astronomical Union.

In accordance with Resolution 5A, the definition of a planet is:

- A “planet” is a celestial body that (a) is in orbit around the Sun, (b) has sufficient mass for its self-gravity to overcome rigid body forces so that it assumes a hydrostatic equilibrium (nearly round) shape, and (c) has cleared the neighborhood around its orbit.

- A “dwarf planet” is a celestial body that (a) is in orbit around the Sun, (b) has sufficient mass for its self-gravity to overcome rigid body forces so that it assumes a hydrostatic equilibrium (nearly round) shape [2], (c) has not cleared the neighborhood around its orbit, and (d) is not a satellite.

- All other objects, except satellites, orbiting the Sun shall be referred to collectively as “Small Solar-System Bodies”.

So why are planets round? Well, part of it is because when objects get particularly massive, nature favors that they assume the most efficient shape. On the other hand, we could say that planets are round because that is how we choose to define the word “planet”. But then again, “a rose by any other name”, right?

We have written many articles about the Solar planets for Universe Today. Here’s Why is the Earth Round?, Why is Everything Spherical?, How was the Solar System Formed?, and here’s Some Interesting Facts About the Planets.

If you’d like more info on the planets, check out NASA’s Solar System exploration page, and here’s a link to NASA’s Solar System Simulator.

We’ve also recorded a series of episodes of Astronomy Cast about every planet in the Solar System. Start here, Episode 49: Mercury.

Sources:

- NASA: Solar System Exploration – Our Solar System

- Wikipedia – Nebular Hypothesis

- COSMOS – Hydrostatic Equilibrium

- Wikipedia – Hydrostatic Equilibrium