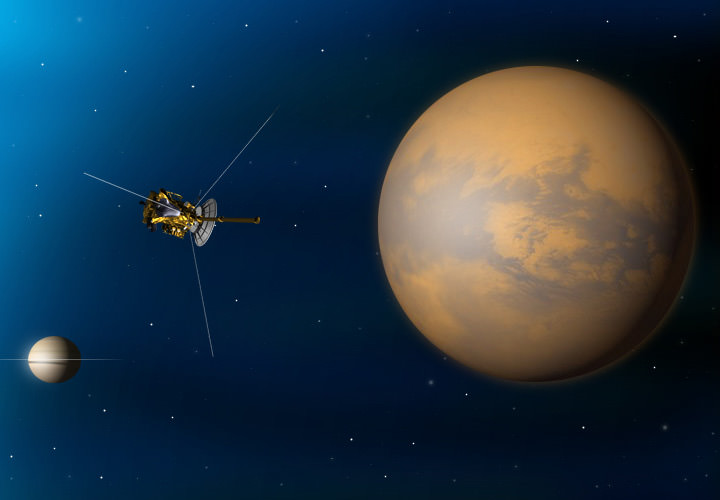

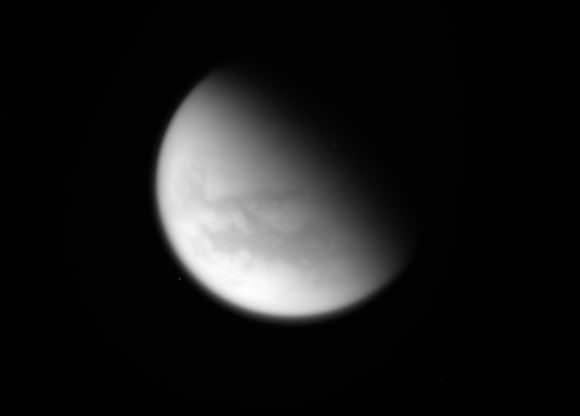

The Cassini spacecraft has done some amazing things since it arrived in the Saturn system in 2004. In addition to providing valuable information on the gas giant and its system of rings, it has also provided us with extensive data and photographs of Saturn’s many moons. Nowhere has this been more apparent than with Saturn’s largest moon, the hydrocarbon-rich satellite known as Titan.

And with just a few hours left before Cassini makes its final plunge between Saturn and its innermost ring (something that no other spacecraft has ever done), we should all take this opportunity to say goodbye to Titan. In the past few years, it has dazzled us with its methane lakes, dense atmosphere, and potential for hosting life. And it shall be sorely missed!

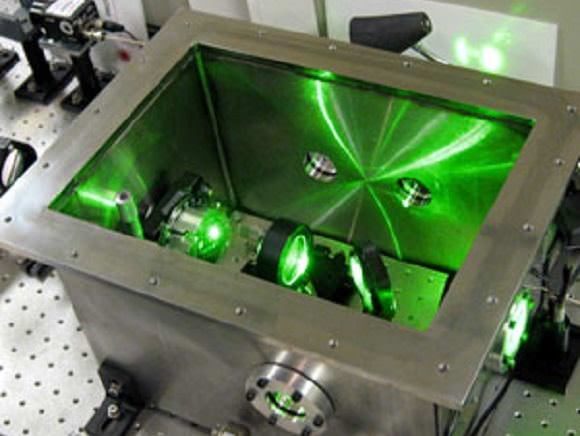

Cassini’s last encounter with Titan – where it passed within 979 km (608 mi) of the moon’s surface – took place on April 21st, at 11:08 p.m. PDT (April 22nd, 2:08 a.m. EDT). The probe also used this opportunity to take some radar images of the moon’s northern polar region. While this area has been photographed before, this was the first time that radar images were acquired.

Over the course of the next week, Cassini’s radar team hopes to pour over theses images, which provide a detailed look at the methane seas and lakes in the northern polar region. It is hoped that this data will allow scientists to shed more light on the depths and compositions of some of the small lakes in the area, as well as provide more information on the evolving surface feature known as “magic island“.

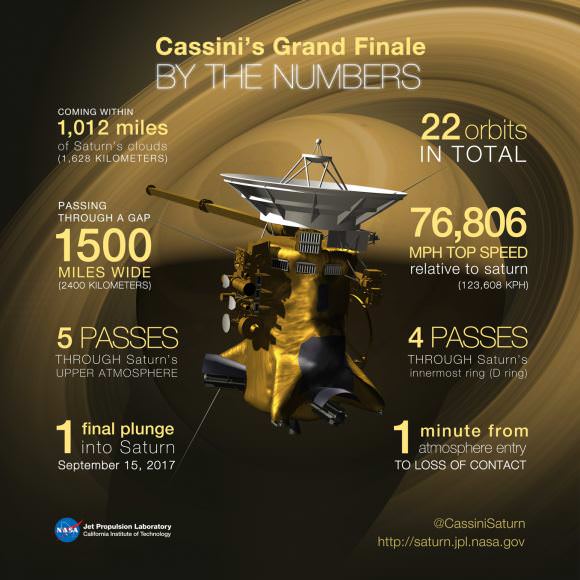

With this last pass complete (its 127th in total), Cassini is now beginning the final phase of its mission – known as the Grand Finale. This will consist of the spacecraft making a final set of 22 orbits around the ringed planet between April 26th and September 15th. The maneuver will allow Cassini to go where no other probe has gone before and get the closest look ever at Saturn’s outer rings.

The final pass over Titan was part of this maneuver, using the moon’s gravity to bend and reshape the probe’s orbit so that it would be able to pass through Saturn’s ring system – instead of passing just beyond the main rings. As Earl Maize, Cassini project manager at JPL, said in a NASA press release:

“With this flyby we’re committed to the Grand Finale. The spacecraft is now on a ballistic path, so that even if we were to forgo future small course adjustments using thrusters, we would still enter Saturn’s atmosphere on Sept. 15 no matter what.”

Cassini’s final pass with Titan allowed it to acquire a boost in velocity, increasing its speed by 860.5 meters per second (3098 km/h; 1,925 mph). It then reached its farthest point in its orbit around Saturn (apoapse) on April 22nd, :46 p.m. PDT (11:46 p.m. EDT). This effectively began the Grand Finale orbits, with the first dive coming on April 26th, at 02:00 a.m. PDT (05:00 a.m. EDT).

This orbit will provide Cassini with its best look to date at Saturn’s north pole, which it will be studying with both its Visible and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS) and Composite Infrared Spectrometer (CIRS). These studies will lead to the creation of the sharpest movies to date in the near-infrared band, which will also allow the science team to study the motions of the hexagon pattern around Saturn’s north pole in more detail.

Between now and September, when the mission will end, the probe will provide information that is expected to improve our understanding of how giant planets form and evolve. Things will finally wrap on September 15th, 2017, when the probe will plunge into Saturn’s atmosphere. But even then, the probe will be sending back information until its very last seconds of operation.

Safe journeys Cassini! And so long Titan! We hope to be exploring you again someday soon, preferably with something that can float or fly around inside your dense atmosphere, or perhaps investigate your methane seas in serious depth!

In the meantime, be sure to check out this narrated, 360-degree animated video from NASA. As you can see, it simulates what a ride on the Cassini spacecraft might look like as it makes its Grand Finale:

Further Reading: NASA, Cassini – The Grand Finale