KENNEDY SPACE CENTER, FL – The SS John Glenn commercial Cygnus resupply vessel arrived at the International Space Station early this morning, April 22, carrying nearly four tons of science and supplies crammed inside for the five person multinational Expedition 51 crew.

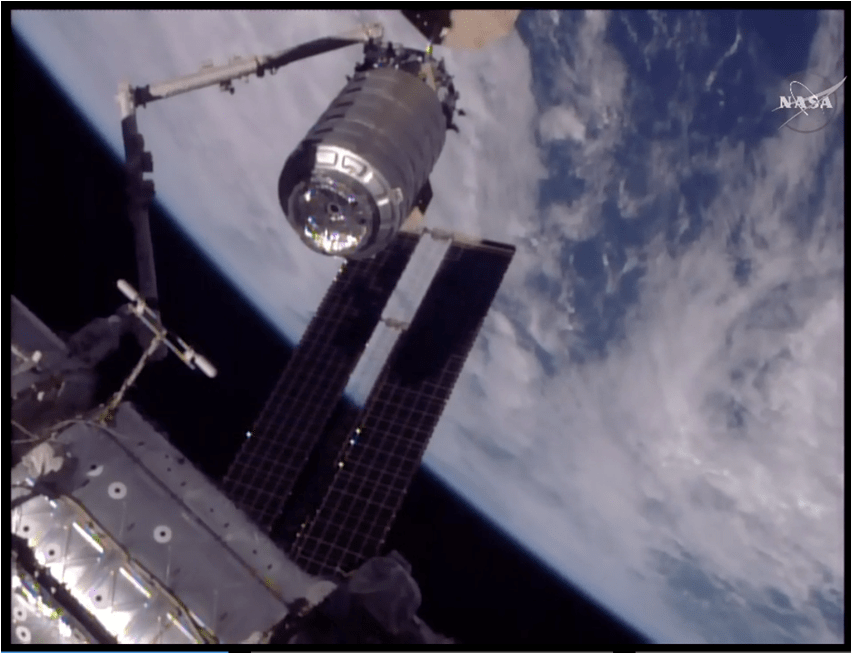

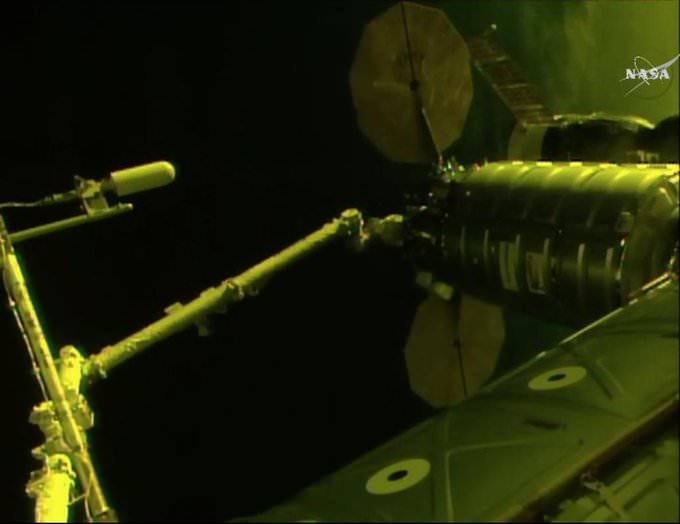

After reaching the vicinity of the space station overnight Saturday, the commercial Cygnus cargo ship was successfully captured by astronaut crew members Thomas Pesquet of ESA (European Space Agency) and Expedition 51 Station Commander Peggy Whitson of NASA at 6:05 a.m. EDT using the stations Canardarm2.

Working at robotic work consoles inside the domed Cupola module, Pesquet and Whitson deftly maneuvered the space station’s 57.7-foot (17.6-meter) Canadian-built Canadarm2 robotic arm to reach out and flawlessly snare the Cygnus CRS-7 spacecraft at 6:05 a.m. EST at the short and tiny grappling pin located at the base of the vessel.

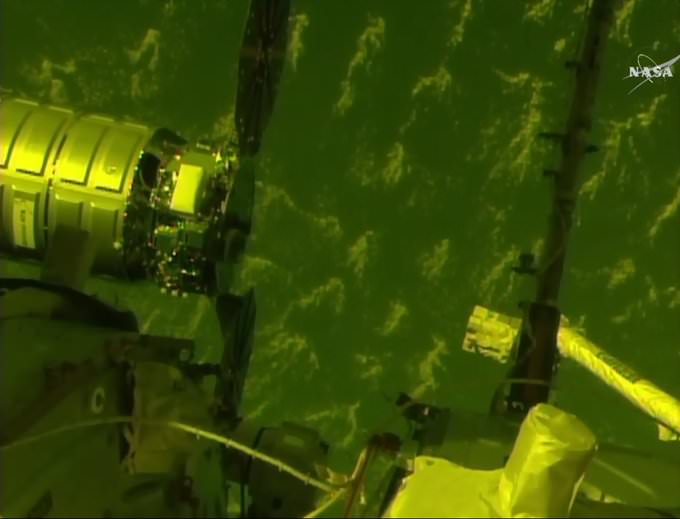

Cygnus and the station were soaring some 250 miles (400 km) over Germany as they were joined at Canada’s high tech arm in a perfect demonstration of the peaceful scientific purpose of the massive laboratory complex.

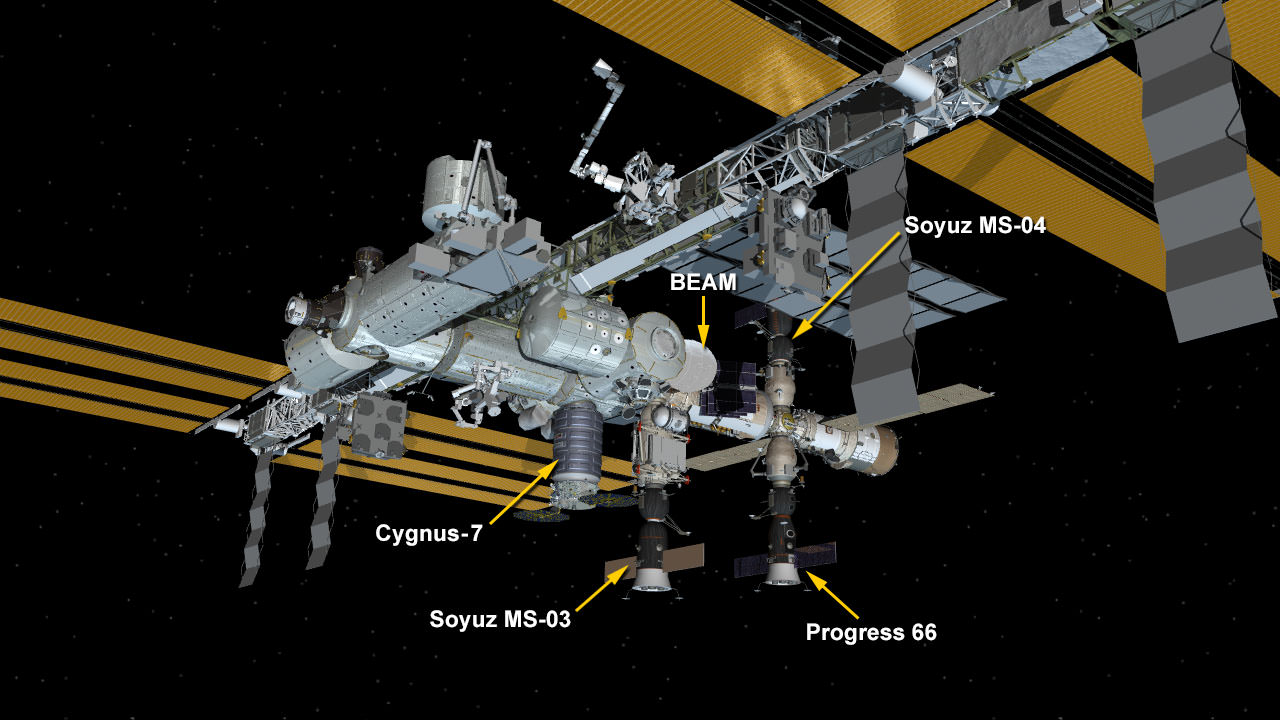

The private supply ship was moved and bolted into place a few hours later at 8:19 a.m. EDT to physically berth and join the station at the Unity module.

Thus begins a three month long sentimental journey ‘bridging history’ to the dawn of America’s human spaceflight with the cylindrically shaped ship named in tribute to John Glenn – the first American to orbit Earth way back in 1962.

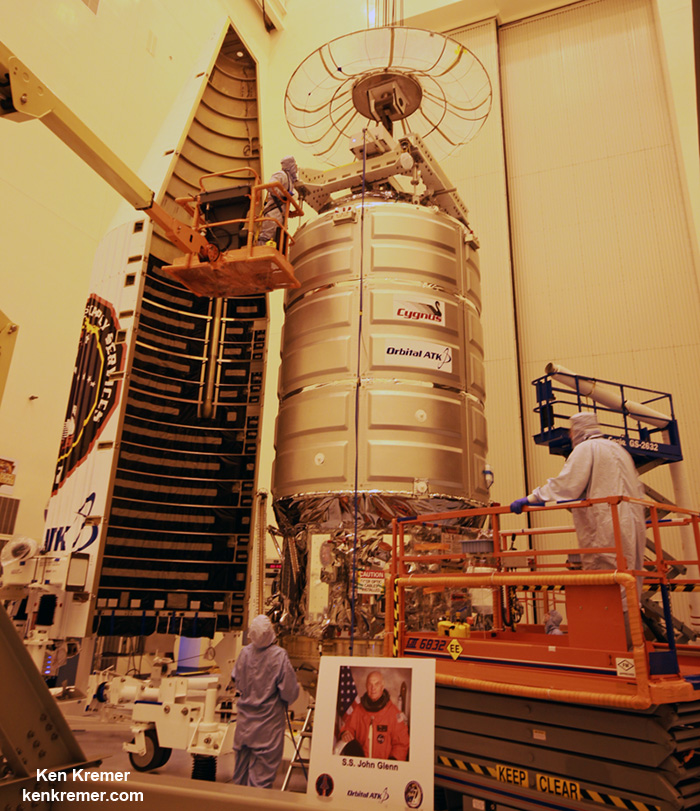

The SS John Glenn is a private Cygnus spacecraft manufactured by Orbital ATK under the commercial resupply services (CRS) contact with NASA whose purpose is to deliver many thousands of pounds of cargo and research supplies to the space station to enable the scientific research for which it was built.

Cygnus arrived at the station via a carefully choreographed series on thruster maneuvers after almost four days in orbit following liftoff earlier this week.

The SS John Glenn blasted to orbit on time at 11:11 a.m. EDT Tuesday, April 18 atop a United Launch Alliance Atlas V rocket from Space Launch Complex 41 on Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida.

The SS John Glenn Cygnus vehicle counts as Orbital ATK’s seventh cargo delivery flight to the station.

The vehicle is also known alternatively as the Cygnus OA-7 or CRS-7 mission.

The entire rendezvous and grappling sequence was broadcast live on NASA TV starting at 4:30 a.m. Saturday: http://nasa.gov/nasatv

“Over the pin. Trigger initiated and snares closed,” radioed Pesquat in the final moments of approach as he carefully and ever so slowly moved the arm towards Cygnus this morning.

“Capture confirmed right on time at 6:05 a.m,” replied Houston Mission Control.

“We have a good capture, and are go for safing,” reported Station Commander Whitson.

“The crew of Expedition 51 would like to congratulate all the teams at NASA, Orbital ATK and the contractors for a flawless cargo-delivery mission,” Pesquat elaborated. “We are very proud to welcome onboard the S.S. John Glenn.”

“The more than three tons of pressurized cargo in the Cygnus spacecraft will be put to good use to continue our mission of research, exploration and discovery. Achievements like this, fruit of the hard work by space agencies and private companies and the international cooperation across the world, are what truly makes the ISS such a special endeavor at the service of all mankind.”

“Station, Houston, well said,” replied Mission Control.

After the astronauts finished their work in orbit, mission controllers in Houston took over and commanded the arm to move Cygnus to the Earth facing port on Node 1 where it was remotely bolted in place with 16 hooks and latches and hard mated to the Unity module.

The mission is named the ‘S.S. John Glenn’ in tribute to legendary NASA astronaut John Glenn – the first American to orbit Earth back in February 1962.

Glenn was one of the original Mercury Seven astronauts selected by NASA. At age 77 he later flew a second mission to space aboard Space Shuttle Discovery- further cementing his status as a true American hero.

Glenn passed away in December 2016 at age 95. He also served four terms as a U.S. Senator from Ohio.

A picture of John Glenn in his shuttle flight suit and a few mementos are aboard.

Cygnus OA-7 is loaded with 3459 kg (7626 pounds) of science experiments and hardware, crew supplies, spare parts, gear and station hardware to the orbital laboratory in support over 250 research experiments being conducted on board by the Expedition 51 and 52 crews. The total volumetric capacity of Cygnus exceeds 27 cubic meters.

Science plays a big role in this mission named in tribute to John Glenn. Over one third of the payload loaded aboard Cygnus involves science.

“The new experiments will include an antibody investigation that could increase the effectiveness of chemotherapy drugs for cancer treatment and an advanced plant habitat for studying plant physiology and growth of fresh food in space,” according to NASA.

The astronauts will grow food in space, including Arabidopsis and dwarf wheat, in an experiment that could lead to providing nutrition to astronauts on a deep space journey to Mars.

“Another new investigation bound for the U.S. National Laboratory will look at using magnetized cells and tools to make it easier to handle cells and cultures, and improve the reproducibility of experiments. Cygnus also is carrying 38 CubeSats, including many built by university students from around the world as part of the QB50 program. The CubeSats are scheduled to deploy from either the spacecraft or space station in the coming months.”

Also aboard is the ‘Genes in Space-2’ experiment. A high school student experiment from Julian Rubinfien of Stuyvescent High School, New York City, to examine accelerated aging during space travel. This first experiment will test if telomere-like DNA can be amplified in space with a small box sized experiment that will be activated by station astronauts.

The Saffire III payload experiment will follow up on earlier missions to study the development and spread of fire and flames in the microgravity environment of space. The yard long experiment is located in the back of the Cygnus vehicle. It will be activated after Cygnus departs the station roughly 80 days after berthing. It will take a few hours to collect the data for transmission to Earth.

Watch for Ken’s onsite launch reports direct from the Kennedy Space Center and Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida.

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Earth and Planetary science and human spaceflight news.