We’re always talking about Mars here on the Guide to Space. And with good reason. Mars is awesome, and there’s a fleet of spacecraft orbiting, probing and crawling around the surface of Mars.

The Red Planet is the focus of so much of our attention because it’s reasonably close and offers humanity a viable place for a second home. Well, not exactly viable, but with the right technology and techniques, we might be able to make a sustainable civilization there.

We have the surface of Mars mapped in great detail, and we know what it looks like from the surface.

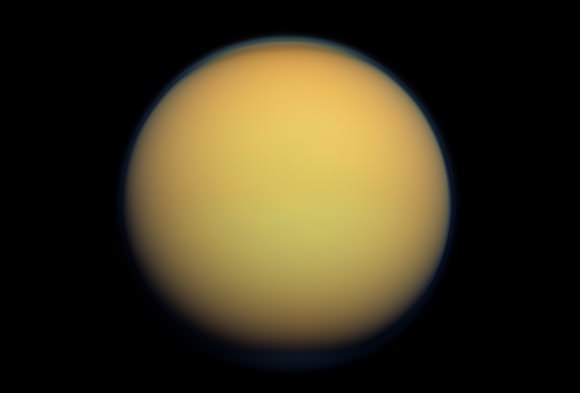

But there’s another planet we need to keep in mind: Venus. It’s bigger, and closer than Mars. And sure, it’s a hellish deathscape that would kill you in moments if you ever set foot on it, but it’s still pretty interesting and mysterious to visit.

Would it surprise you to know that many spacecraft have actually made it down to the surface of Venus, and photographed the place from the ground? It was an amazing feat of Soviet engineering, and there are some new technologies in the works that might help us get back, and explore it longer.

Today, let’s talk about the Soviet Venera program. The first time humanity saw Venus from its surface.

Back in the 60s, in the height of the cold war, the Americans and the Soviets were racing to be the first to explore the Solar System. First satellite to orbit Earth (Soviets), first human to orbit Earth (Soviets), first flyby and landing on the Moon (Soviets), first flyby of Mars (Americans), first flyby of Venus (Americans), etc.

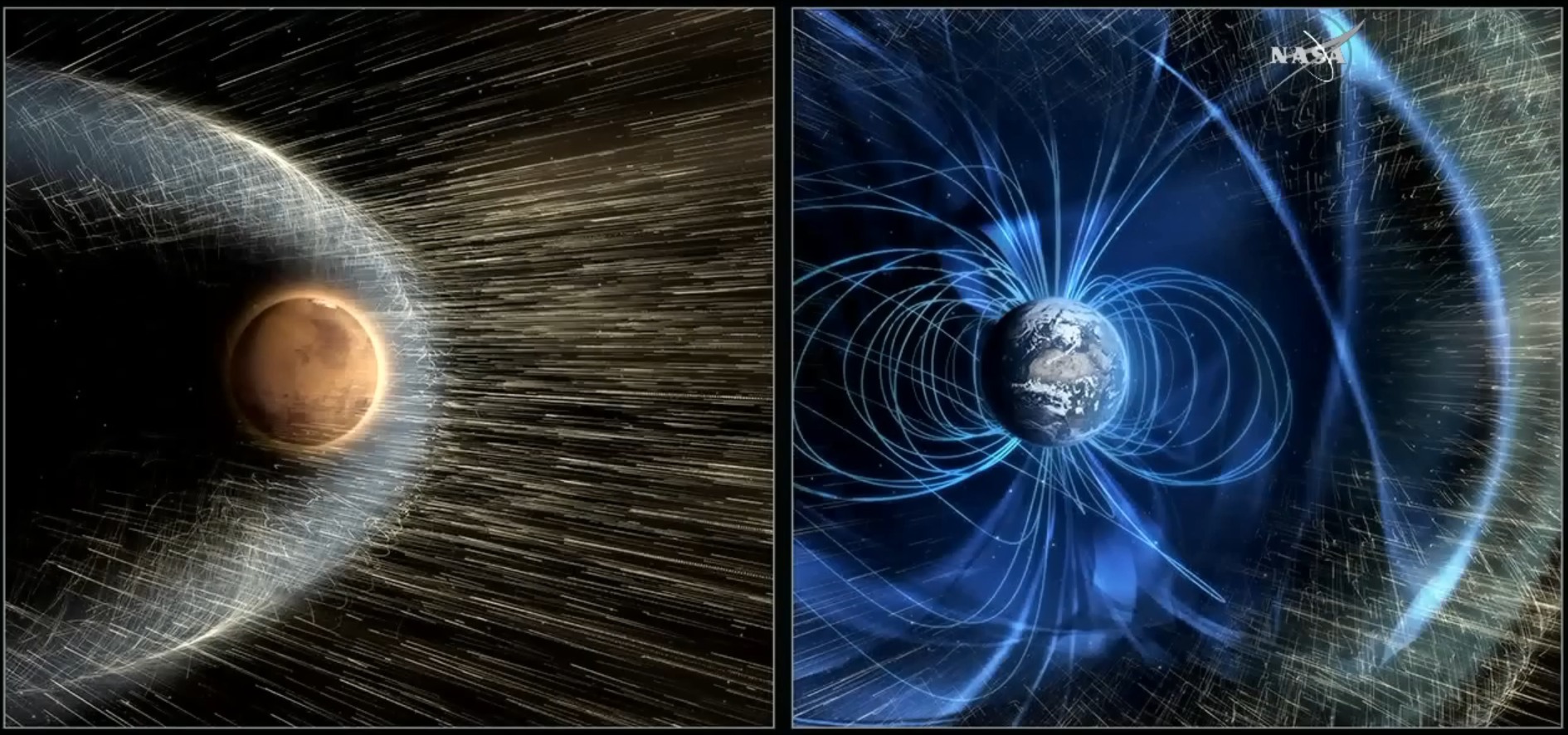

The Soviets set their sights on putting a lander down on the surface of Venus. But as we know, this planet has some unique challenges. Every place on the entire planet measures the same 462 degrees C (or 864 F).

Furthermore, the atmospheric pressure on the surface of Venus is 90 times greater than Earth. Being down at the bottom of that column of atmosphere is the same as being beneath a kilometer of ocean on Earth. Remember those submarine movies where they dive too deep and get crushed like a soda can?

Finally, it rains sulphuric acid. I mean, that’s really irritating.

Needless to say, figuring this out took the Soviets a few tries.

Their first attempts to even flyby Venus was Venera 1, on February 4, 1961. But it failed to even escape Earth orbit. This was followed by Venera 2, launched on November 12, 1965, but it went off course just after launch.

Venera 3 blasted off on November 16, 1965, and was intended to land on the surface of Venus. The Soviets lost communication with the spacecraft, but it’s believed it did actually crash land on Venus. So I guess that was the first successful “landing” on Venus?

Before I continue, I’d like to talk a little bit about landing on planets. As we’ve discussed in the past, landing on Mars is really really hard. The atmosphere is thick enough that spacecraft will burn up if you aim directly for the surface, but it’s not thick enough to let you use parachutes to gently land on the surface.

Landing on the surface of Venus on the other hand, is super easy. The atmosphere is so thick that you can use parachutes no problem. If you can get on target and deploy a parachute capable of handling the terrible environment, your soft landing is pretty much assured. Surviving down there is another story, but we’ll get to that.

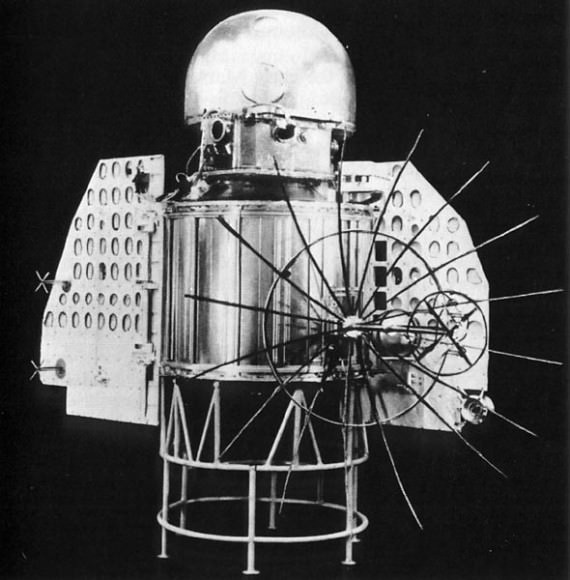

Venera 4 came next, launched on June 12, 1967. The Soviet scientists had few clues about what the surface of Venus was actually like. They didn’t know the atmospheric pressure, guessing it might be a little higher pressure than Earth, or maybe it was hundreds of times our pressure. It was tested with high temperatures, and brutal deceleration. They thought they’d built this thing plenty tough.

Venera 4 arrived at Venus on October 18, 1967, and tried to survive a landing. Temperatures on its heat shield were clocked at 11,000 C, and it experienced 300 Gs of deceleration.

The initial temperature 52 km was a nice 33C, but then as it descended down towards the surface, temperatures increased to 262 C. And then, they lost contact with the probe, killed dead by the horrible temperature.

We can assume it landed, though, and for the first time, scientists caught a glimpse of just how bad it is down there on the surface of Venus.

Venera 5 was launched on January 5, 1969, and was built tougher, learning from the lessons of Venera 4. It also made it into Venus’ atmosphere, returned some interested science about the planet and then died before it reached the surface.

Venera 6 followed, same deal. Built tougher, died in the atmosphere, returned some useful science.

Venera 7 was built with a full understanding of how bad it was down there on Venus. It launched on August 17, 1970, and arrived in December. It’s believed that the parachutes on the spacecraft only partially deployed, allowing it to descend more quickly through the Venusian atmosphere than originally planned. It smacked into the surface going about 16.5 m/s, but amazingly, it survived, and continued to send back a weak signal to Earth for about 23 minutes.

For the first time ever, a spacecraft had made it down to the surface of Venus and communicated its status. I’m sure it was just 23 minutes of robotic screaming, but still, progress. Scientists got their first accurate measurement of the temperatures, and pressure down there.

Bottom line, humans could never survive on the surface of Venus.

Venera 8 blasted off for Venus on March 17, 1972, and the Soviet engineers built it to survive the descent and landing as long as possible. It made it through the atmosphere, landed on the surface, and returned data for about 50 minutes. It didn’t have a camera, but it did have a light sensor, which told scientists being on Venus was kind of like Earth on an overcast day. Enough light to take pictures… next time.

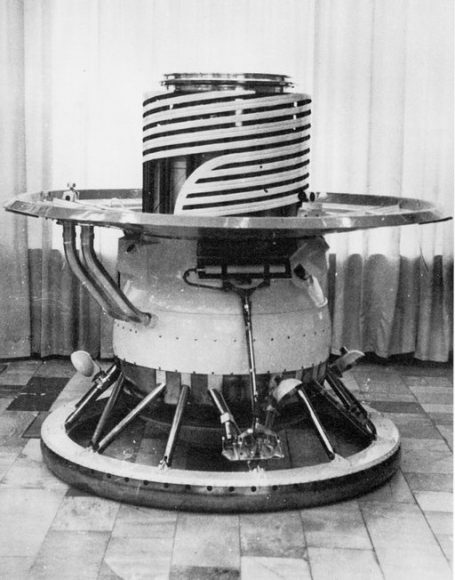

For their next missions, the Soviets went back to the drawing board and built entirely new landing craft. Built big, heavy and tough, designed to get to the surface of Venus and survive long enough to send back data and pictures.

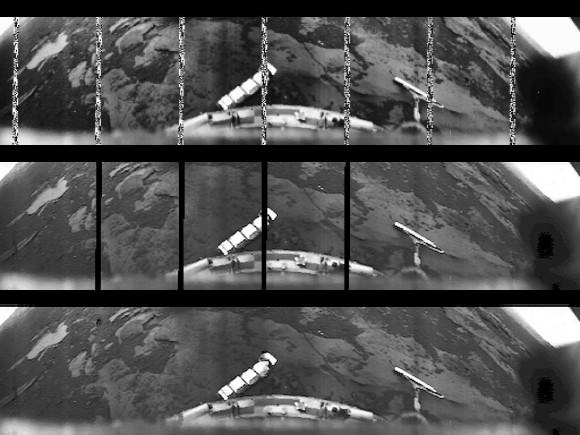

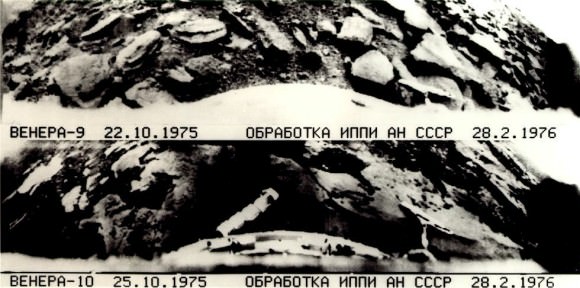

Venera 9 was launched on June 8, 1975. It survived the atmospheric descent and landed on the surface of Venus. The lander was built like a liquid cooled reverse insulated pressure vessel, using circulating fluid to keep the electronics cooled as long as possible. In this case, that was 53 minutes. Venera 9 measured clouds of acid, bromine and other toxic chemicals, and sent back grainy black and white television pictures from the surface of Venus.

In fact, these were the first pictures ever taken from the surface of another planet.

Venera 10 lasted for 65 minutes and took pictures of the surface with one camera. The lens cap on a second camera didn’t release. The spacecraft saw lava rocks with layers of other rocks in between. Similar environments that you might see here on Earth.

Venera 11 was launched on September 9, 1975 and lasted for 95 minutes on the surface of Venus. In addition to confirming the horrible environment discovered by the other landers, Venera 11 detected lightning strikes in the vicinity. It was equipped with a color camera, but again, the lens cap failed to deploy for it or the black and white camera. So it failed to send any pictures home.

Venera 12 was launched on September 14, 1978, and made it down to the surface of Venus. It lasted 110 minutes and returned detailed information about the chemical composition of the atmosphere. Unfortunately, both its camera lens caps failed to deploy, so no pictures were returned. And pictures are what we really care about, right?

Venera 13 was built on the same tougher, beefier design, and was blasted off to Venus on October 30, 1981, and this one was a tremendous success. It landed on Venus and survived for 127 minutes. It took pictures of its surroundings using two cameras peering through quartz windows, and saw a landscape of bedrock. It used spring-loaded arms to test out how compressible the soil was.

Venera 14 was identical and launched just 5 days after Venera 13. It also landed and survived for 57 minutes. Unfortunately, its experiment to test the compressibility of the soil was a botch because one of its lens caps landed right under its spring-loaded arm. But apart from that, it sent back color pictures of the hellish landscape.

And with that, the Soviet Venus landing program ended. And since then, no additional spacecraft have ever returned to the surface of Venus.

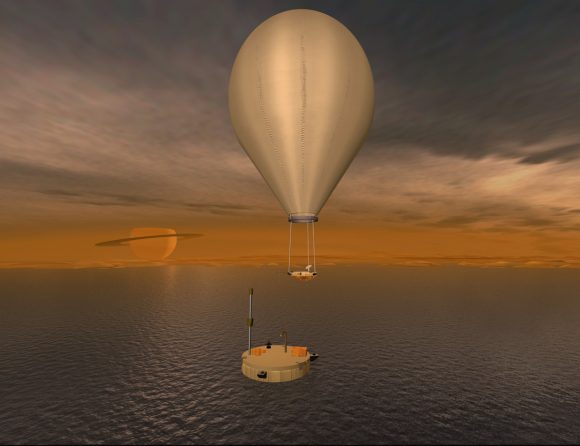

It’s one thing for a lander to make it to the surface of Venus, last a few minutes and then die from the horrible environment. What we really want is some kind of rover, like Curiosity, which would last on the surface of Venus for weeks, months or even years and do more science.

And computers don’t like this kind of heat. Go ahead, put your computer in the oven and set it to 850. Oh, your oven doesn’t go to 850, that’s fine, because it would be insane. Seriously, don’t do that, it would be bad.

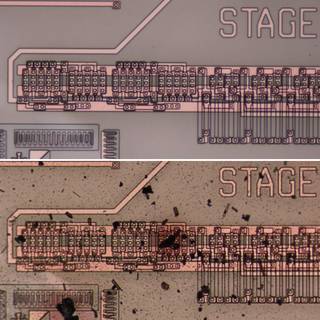

Engineers at NASA’s Glenn Research Center have developed a new kind of electrical circuitry that might be able to handle those kinds of temperatures. Their new circuits were tested in the Glenn Extreme Environments Rig, which can simulate the surface of Venus. It can mimic the temperature, pressure and even the chemistry of Venus’ atmosphere.

The circuitry, originally designed for hot jet engines, lasted for 521 hours, functioning perfectly. If all goes well, future Venus rovers could be developed to survive on the surface of Venus without needing the complex and short lived cooling systems.

This discovery might unleash a whole new era of exploration of Venus, to confirm once and for all that it really does suck.

While the Soviets had a tough time with Mars, they really nailed it with Venus. You can see how they built and launched spacecraft after spacecraft, sticking with this challenge until they got the pictures and data they were looking for. I really think this series is one of the triumphs of robotic space exploration, and I look forward to future mission concepts to pick up where the Soviets left off.

Are you excited about the prospects of exploring Venus with rovers? Let me know your thoughts in the comments.