When galaxies collide, the result is nothing short of spectacular. While this type of event only takes place once every few billion years (and takes millions of years to complete), it is actually pretty common from a cosmological perspective. And interestingly enough, one of the most impressive consequences – stars being ripped apart by supermassive black holes (SMBHs) – is quite common as well.

This process is known in the scientific community as stellar cannibalism, or Tidal Disruption Events (TDEs). Until recently, astronomers believed that these sorts of events were very rare. But according to a pioneering study conducted by leading scientists from the University of Sheffield, it is actually 100 times more likely than astronomers previously suspected.

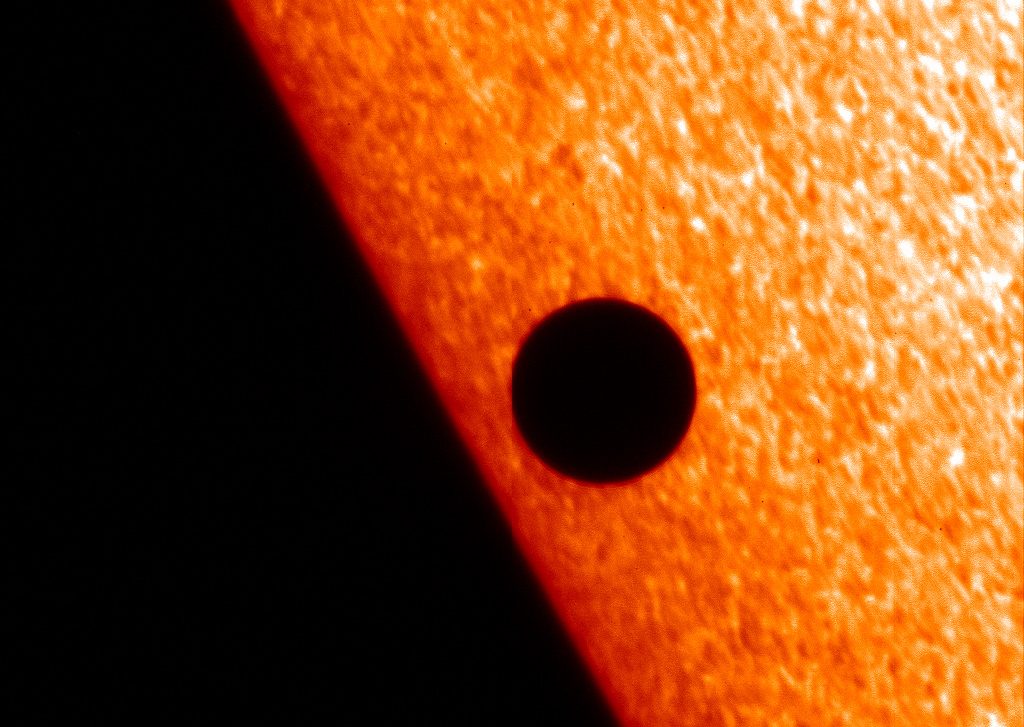

TDEs were first proposed in 1975 as an inevitable consequence of black holes being present at the center of galaxies. When a star passes close enough to be subject to the tidal forces of a SMBH it undergoes what is known as “spaghetification”, where material is slowly pulled away and forms string-like shapes around the black hole. The process causes dramatic flare ups that can be billions of times brighter than all the stars in the galaxy combined.

Since the gravitational force of black holes is so strong that even light cannot escape their surfaces (thus making them invisible to conventional instruments), TDEs can be used to locate SMBHs at the center of galaxies and study how they accrete matter. Previously, astronomers have relied on large-area surveys to determine the rate at which TDEs happen, and concluded that they occur at a rate of once every 10,000 to 100,000 years per galaxy.

However, using the William Herschel Telescope at the Roque de los Muchachos Observatory on the island of La Palma, the team of scientists – who hail from Sheffield’s Department of Physics and Astronomy – conducted a survey of 15 ultra-luminous infrared galaxies that were undergoing galactic collisions. When comparing information on one galaxy that had been observed twice over a ten year period, they noticed that a TDE was taking place.

Their findings were detailed in a study titled “A tidal disruption event in the nearby ultra-luminous infrared galaxy F01004-2237“, which appeared recently in the journal Nature: Astronomy. As Dr James Mullaney, a Lecturer in Astronomy at Sheffield and a co-author of the study, said in a University press release:

“Each of these 15 galaxies is undergoing a ‘cosmic collision’ with a neighboring galaxy. Our surprising findings show that the rate of TDEs dramatically increases when galaxies collide. This is likely due to the fact that the collisions lead to large numbers of stars being formed close to the central supermassive black holes in the two galaxies as they merge together.”

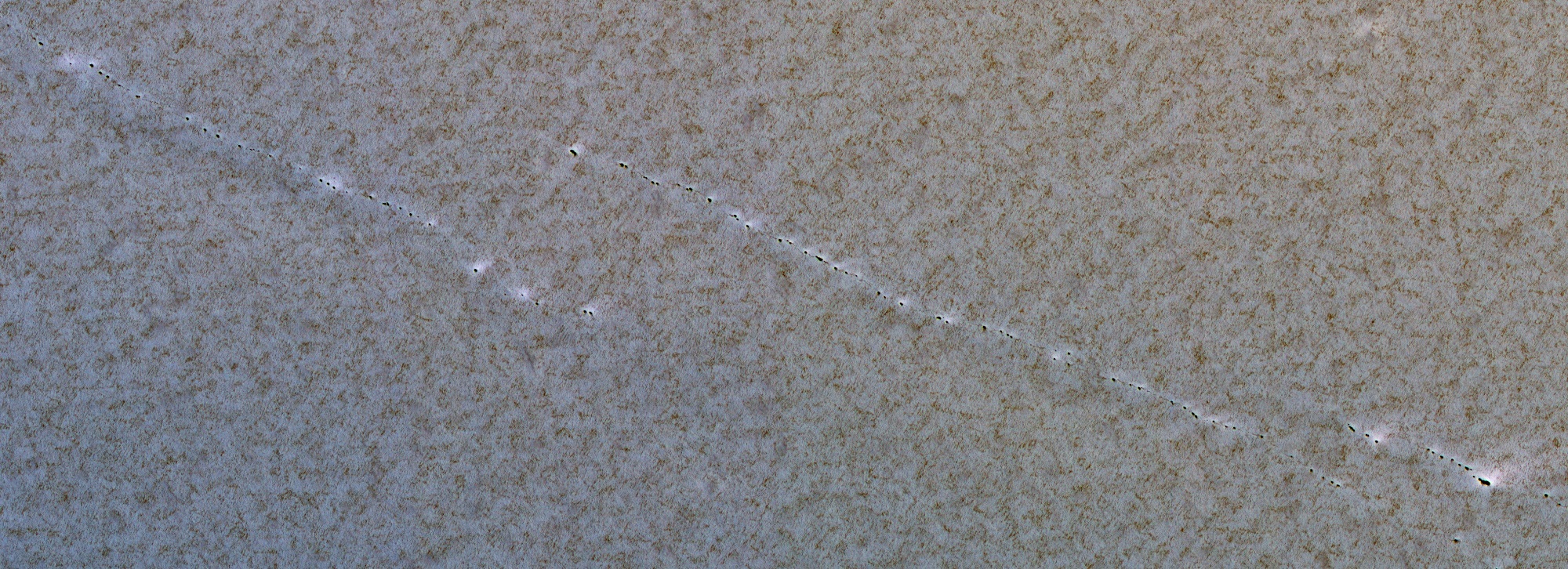

The Sheffield team first observed these 15 colliding galaxies in 2005 during a previous survey. However, when they observed them again in 2015, they noticed that one of the galaxies in the sample – F01004-2237 – appeared to have undergone some changes. The team them consulted data from the Hubble Space Telescope and the Catalina Sky Survey – which monitors the brightness of astronomical objects (particularly NEOs) over time.

What they found was that the brightness of F01004-2237 – which is about 1.7 billion light years from Earth – had changed dramatically. Ordinarily, such flare ups would be attributed to a supernova or matter being accreted onto an SMBH at the center (aka. an active galactic nucleus). However, the nature of this flare up (which showed unusually strong and broad helium emission lines in its post-flare spectrum) was more consistent with a TDE.

The appearance of such an event had been detected during a repeat spectroscopic observations of a sample of 15 galaxies over a period of just 10 years suggested that the rate at which TDEs happen was far higher than previously thought – and by a factor of 100 no less. As Clive Tadhunter, a Professor of Astrophysics at the University of Sheffield and lead author of the study, said:

“Based on our results for F01004-2237, we expect that TDE events will become common in our own Milky Way galaxy when it eventually merges with the neighboring Andromeda galaxy in about 5 billion years. Looking towards the center of the Milky Way at the time of the merger we’d see a flare approximately every 10 to 100 years. The flares would be visible to the naked eye and appear much brighter than any other star or planet in the night sky.”

In the meantime, we can expect that TDEs are likely to be noticed in other galaxies within our own lifetimes. The last time such an event was witnessed directly was back in 2015, when the All-Sky Automated Survey for Supernovae (aka. ASAS-SN, or Assassin) detected a superlimunous event four billion light years away – which follow-up investigations revealed was a star being swallowed by a spinning SMBH.

Naturally, news of this was met with a fair degree of excitement from the astronomical community, since it was such a rare event. But if the results of this study are any indication, astronomers should be noticing plenty more stars being slowly ripped apart in the not-too-distant future.

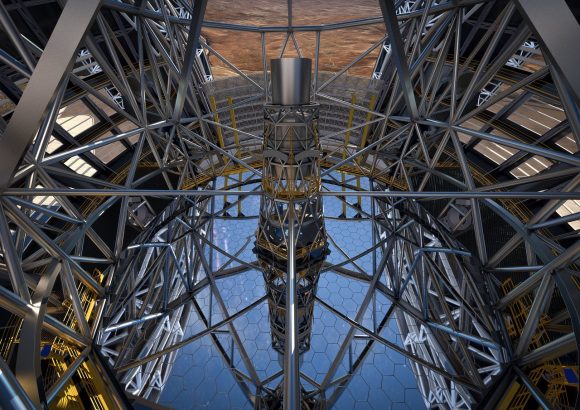

With improvements in instrumentation, and next-generation instruments like the James Webb Telescope being deployed in the coming years, these rare and extremely picturesque events may prove to be a more common experience.

Further Reading: Nature: Astronomy, University of Sheffield