Humanity’s understanding of what constitutes a planet has changed over time. Whereas our most notable magi and scholars once believed that the world was a flat disc (or ziggurat, or cube), they gradually learned that it was in fact spherical. And by the modern era, they came to understand that the Earth was merely one of several planets in the known Universe.

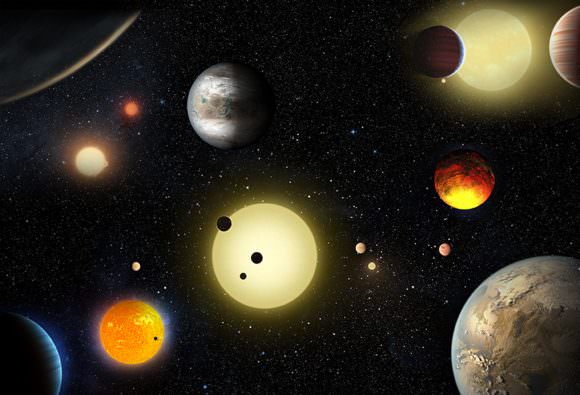

And yet, our notions of what constitutes a planet are still evolving. To put it simply, our definition of planet has historically been dependent upon our frame of reference. In addition to discovering extra-solar planets that have pushed the boundaries of what we consider to be normal, astronomers have also discovered new bodies in our own backyard that have forced us to come up with new classification schemes.

History of the Term:

To ancient philosophers and scholars, the Solar Planets represented something entirely different than what they do today. Without the aid of telescopes, the planets looked like particularly bright stars that moved relative to the background stars. The earliest records on the motions of the known planets date back to the 2nd-millennium BCE, where Babylonian astronomers laid the groundwork for western astronomy and astrology.

These include the Venus tablet of Ammisaduqa, which catalogued the motions of Venus. Meanwhile, the 7th-century BCE MUL.APIN tablets laid out the motions of the Sun, the Moon, and the then-known planets over the course of the year (Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn). The Enuma anu enlil tablets, also dated to the 7th-century BCE, were a collection of all the omens assigned to celestial phenomena and the motions of the planets.

By classical antiquity, astronomers adopted a new concept of planets as bodies that orbited the Earth. Whereas some advocated a heliocentric system – such as 3rd-century BCE astronomer Aristarchus of Samos and 1st-century BCE astronomer Seleucus of Seleucia – the geocentric view of the Universe remained the most widely-accepted one. Astronomers also began creating mathematical models to predict their movements during this time.

This culminated in the 2nd century CE with Ptolemy’s (Claudius Ptolemaeus) publication of the Almagest, which became the astronomical and astrological canon in Europe and the Middle East for over a thousand years. Within this system, the known planets and bodies (even the Sun) all revolved around the Earth. In the centuries that followed, Indian and Islamic astronomers would added to this system based on their observations of the heavens.

By the time of the Scientific Revolution (ca. 15th – 18th centuries), the definition of planet began to change again. Thanks to Nicolaus Copernicus, Galileo Galilei, and Johannes Kepler, who proposed and advanced the heliocentric model of the Solar System, planets became defined as objects that orbited the Sun and not Earth. The invention of the telescope also led to an improved understanding of the planets, and their similarities with Earth.

Between the 18th and 20th centuries, countless new objects, moons and planets were discovered. This included Ceres, Vesta, Pallas (and the Main Asteroid Belt), the planets Uranus and Neptune, and the moons of Mars and the gas giants. And then in 1930, Pluto was discovered by Clyde Tombaugh, which was designated as the 9th planet of the Solar System.

Throughout this period, no formal definition of planet existed. But an accepted convention existed where a planet was used to described any “large” body that orbited the Sun. This, and the convention of a nine-planet Solar System, would remain in place until the 21st century. By this time, numerous discoveries within the Solar System and beyond would lead to demands that a formal definition be adopted.

Working Group on Extrasolar Planets:

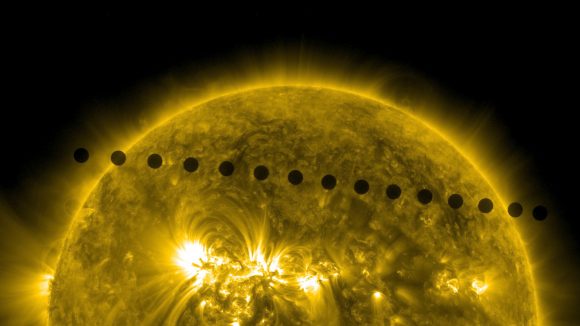

While astronomers have long held that other star systems would have their own system of planets, the first reported discovery of a planet outside the Solar System (aka. extrasolar planet or exoplanet) did not take place until 1992. At this time, two radio astronomers working out of the Arecibo Observatory (Aleksander Wolszczan and Dale Frail) announced the discovery of two planets orbiting the pulsar PSR 1257+12.

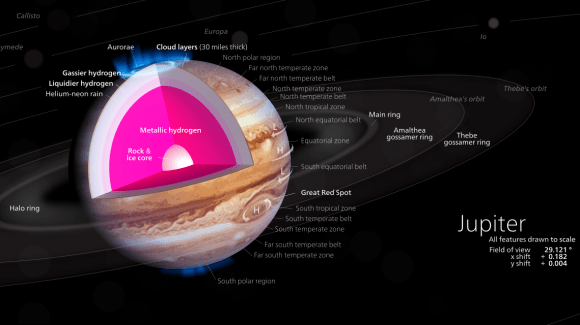

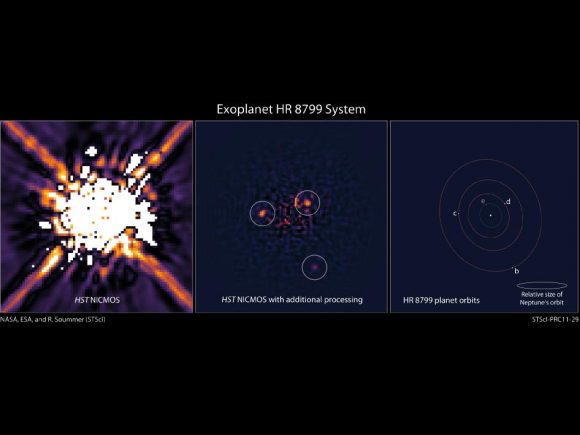

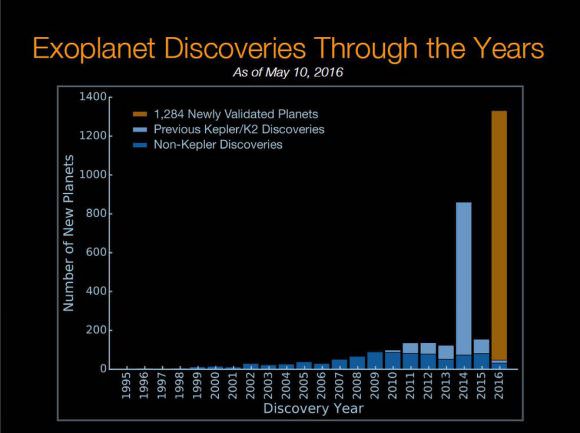

The first confirmed discovery took place in 1995, when astronomers from the University of Geneva (Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz) announced the detection of 51 Pegasi. Between the mid-90s and the deployment of the Kepler space telescope in 2009, the majority of extrasolar planets were gas giants that were either comparable in size and mass to Jupiter or significantly larger (i.e. “Super-Jupiters”).

These new discoveries led the International Astronomical Union (IAU) to create the Working Group of Extrasolar Planets (WGESP) in 1999. The stated purpose of the WGESP was to “act as a focal point for international research on extrasolar planets.” As a result of this ongoing research, and the detection of numerous extra-solar bodies, attempts were made to clarify the nomenclature.

As of February 2003, the WGESP indicated that it had modified its position and adopted the following “working definition” of a planet:

1) Objects with true masses below the limiting mass for thermonuclear fusion of deuterium (currently calculated to be 13 Jupiter masses for objects of solar metallicity) that orbit stars or stellar remnants are “planets” (no matter how they formed). The minimum mass/size required for an extrasolar object to be considered a planet should be the same as that used in our Solar System.

2) Substellar objects with true masses above the limiting mass for thermonuclear fusion of deuterium are “brown dwarfs”, no matter how they formed nor where they are located.

3) Free-floating objects in young star clusters with masses below the limiting mass for thermonuclear fusion of deuterium are not “planets”, but are “sub-brown dwarfs” (or whatever name is most appropriate).

As of January 22nd, 2017, more than 2000 exoplanet discoveries have been confirmed, with 3,565 exoplanet candidates being detected in 2,675 planetary systems (including 602 multiple planetary systems).

2006 IAU Resolution:

During the early-to-mid 2000s, numerous discoveries were made in the Kuiper Belt that also stimulated the planet debate. This began with the discovery of Sedna in 2003 by a team of astronomers (Michael Brown, Chad Trujillo and David Rabinowitz) working at the Palomar Observatory in San Diego. Ongoing observations confirmed that it was approx 1000 km in diameter, and large enough to undergo hydrostatic equilibrium.

This was followed by the discovery of Eris – an even larger object (over 2000 km in diameter) – in 2005, again by a team consisting of Brown, Trujillo, and Rabinowitz. This was followed by the discovery of Makemake on the same day, and Haumea a few days later. Other discoveries made during this period include Quaoar in 2002, Orcus in 2004, and 2007 OR10 in 2007.

The discovery of a several objects beyond Pluto’s orbit that were large enough to be spherical led to efforts on behalf of the IAU to adopt a formal definition of a planet. By October 2005, a group of 19 IAU members narrowed their choices to a shortlist of three characteristics. These included:

- A planet is any object in orbit around the Sun with a diameter greater than 2000 km. (eleven votes in favour)

- A planet is any object in orbit around the Sun whose shape is stable due to its own gravity. (eight votes in favour)

- A planet is any object in orbit around the Sun that is dominant in its immediate neighbourhood. (six votes in favour)

After failing to reach a consensus, the committee decided to put these three definitions to a wider vote. This took place in August of 2006 at the 26th IAU General Assembly Meeting in Prague. On August 24th, the issue was put to a final draft vote, which resulted in the adoption of a new classification scheme designed to distinguish between planets and smaller bodies. These included:

(1) A “planet” is a celestial body that (a) is in orbit around the Sun, (b) has sufficient mass for its self-gravity to overcome rigid body forces so that it assumes a hydrostatic equilibrium (nearly round) shape, and (c) has cleared the neighborhood around its orbit.

(2) A “dwarf planet” is a celestial body that (a) is in orbit around the Sun, (b) has sufficient mass for its self-gravity to overcome rigid body forces so that it assumes a hydrostatic equilibrium (nearly round) shape, (c) has not cleared the neighborhood around its orbit, and (d) is not a satellite.

(3) All other objects, except satellites, orbiting the Sun shall be referred to collectively as “Small Solar-System Bodies”.

In accordance with this resolution, the IAU designated Pluto, Eris, and Ceres into the category of “dwarf planet”, while other Trans-Neptunian Objects (TNOs) were left undeclared at the time. This new classification scheme spawned a great deal of controversy and some outcries from the astronomical community, many of whom challenged the criteria as being vague and debatable in their applicability.

For instance, many have challenged the idea of a planet clearing its neighborhood, citing the existence of near-Earth Objects (NEOs), Jupiter’s Trojan Asteroids, and other instances where large planets share their orbit with other objects. However, these have been countered by the argument that these large bodies do not share their orbits with smaller objects, but dominate them and carry them along in their orbits.

Another sticking point was the issue of hydrostatic equilibrium, which is the point where a planet has sufficient mass that it will collapse under the force of its own gravity and become spherical. The point at which this takes place remains entirely unclear thought, and some astronomers therefore challenge it being included as a criterion.

In addition, some astronomers claim that these newly-adopted criteria are only useful insofar as Solar planets are concerned. But as exoplanet research has shown, planets in other star star systems can be significantly different. In particular, the discovery of numerous “Super Jupiters” and “Super Earths” has confounded conventional notions of what is considered normal for a planetary system.

In June 2008, the IAU executive committee announced the establishment of a subclass of dwarf planets in the hopes of clarifying the definitions further. Comprising the recently-discovered TNOs, they established the term “plutoids”, which would thenceforth include Pluto, Eris and any other future trans-Neptunian dwarf planets (but excluded Ceres). In time, Haumea, Makemake, and other TNOs were added to the list.

Despite these efforts and changes in nomenclature, for many, the issue remains far from resolved. What’s more, the possible existence of Planet 9 in the outer Solar System has added more weight to the discussion. And as our research into exoplanets continues – and uncrewed (and even crewed) mission are made to other star systems – we can expect the debate to enter into a whole new phase!

We have written many interesting articles about the planets here at Universe Today. Here’s How Many Planets are there in the Solar System?, What are the Planets of the Solar System, The Planets of our Solar System in Order of Size, Why Pluto is no Longer a Planet, Evidence Continues to Mount for Ninth Planet, and What are Extrasolar Planets?.

For more information, take a look at this article from Scientific American, What is a Planet?, and the video archive from the IAU.

Astronomy Cast has an episode on Pluto’s planetary identity crisis.

Sources: