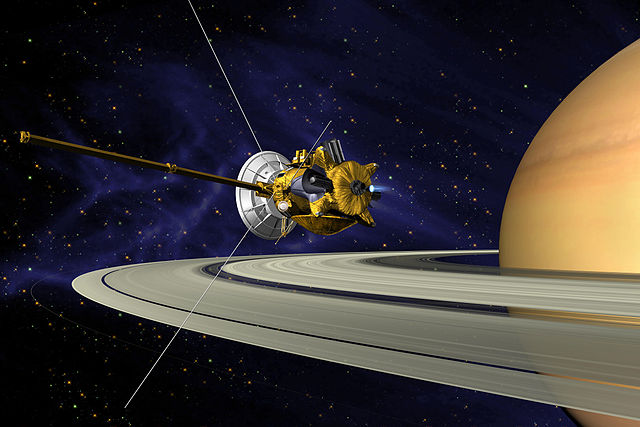

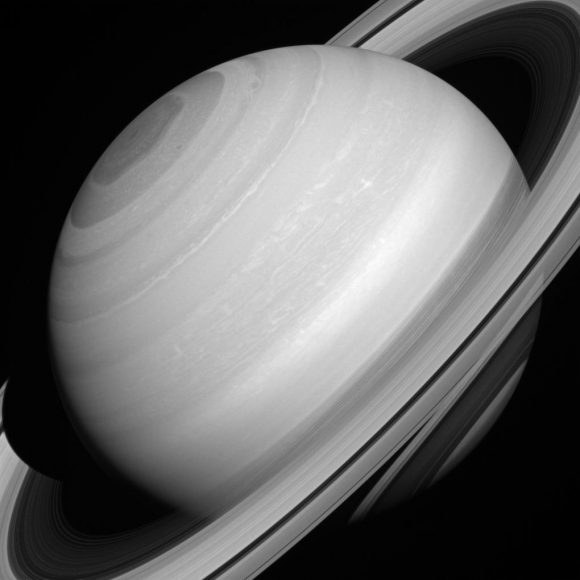

When Cassini Project Scientist Linda Spilker thinks about her spacecraft, as it is out there gliding amidst the moons and rings of Saturn, there are times when she envisions it as a dancer or ice skater, spinning and turning to look at all the different targets.

“I picture Cassini as a she,” Spilker said, admitting to moments of anthropomorphizing, “because all good sailing ships are a she. She has these beautiful gold thermal blankets, and I see them as her golden flowing hair. I think she’s very joyful and curious and is definitely an explorer. That’s my view of what Cassini looks like.”

Does your spacecraft seem to have a personality?

That’s a question I asked every scientist and engineer who I interviewed for my book “Incredible Stories From Space: A Behind-the-Scenes Look at the Missions Changing Our View of the Cosmos,” which comes out on Dec. 20, 2016. The answers varied, sometimes even among people who worked on the same mission. But, it seems, we humans can’t help but sometimes think of our robots as being just like us.

“There is a personality there,” Spilker said of the Cassini spacecraft, “and I think it is a reflection of the Cassini team. We take good care of her and watch over her, making sure everything goes right. And if she curls up in the middle of the night and says ‘Help!’ we all come in and want to fix her and get her running again.”

But during its 13-year mission, the Cassini spacecraft has had few anomalies and difficulties. As the Cassini team gears up towards the end of the mission in September 2017, they look back with amazement, gratitude and a sense of accomplishment.

“Everything about the spacecraft is rock solid,” said Cassini Project Manager Earl Maize. “There were really no compromises in the hardware whatsoever. All the design lessons learned from Galileo, Voyager and Magellan went into Cassini.”

Plus, the spacecraft engineering and science teams have been absolutely meticulous in managing the mission, Maize said.

“If we find an idiosyncrasy that looks like it might trend into an issue, we work around it. We have cranky reaction wheels, and we have nursed them. Plus the spacecraft has been very good at diagnosing itself and the team is very good at working through the issues. We’ve had very few difficulties in flight,” Maize said, grinning, looking towards the wooden table in front of us, and giving it a few knocks. “It looks good for us to finish up the mission strong.”

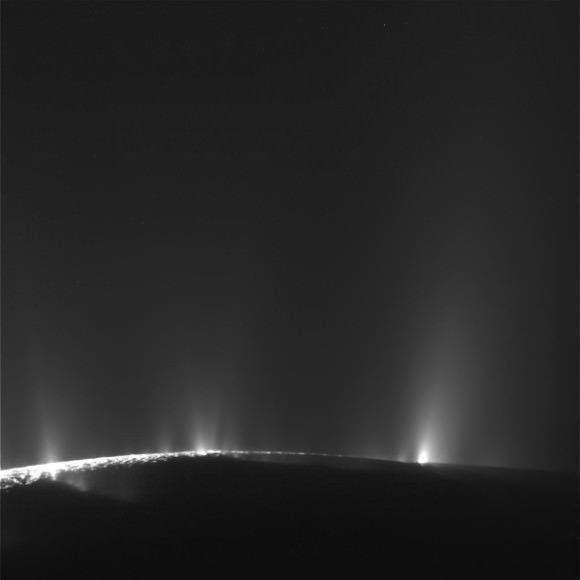

The 37 NASA scientists and engineers I interviewed for over a dozen different missions all had stories to tell and they all had their favorites. Maize said the main story of the Cassini is its durability and endurance. Launched in 1997, the spacecraft arrived at Saturn in 2004. Over the years, Cassini’s findings have revolutionized our understanding of the entire Saturn system, providing intriguing insights on Saturn itself as well as revealing secrets held by moons such as Enceladus and Titan.

“The main story is the longevity,” Maize said. “Voyager will always have us beat, because Cassini is an orbiter and it has certain sets of consumables – for example, the propellant — that will run out. But the longevity of the mission is a tribute to the developers. We had some amazing system engineers whose history of working on previous missions will likely never be repeated.”

Like many of those engineers, early in her career as a planetary scientist, Spilker worked on the Voyager mission.

“After the Voyager flybys of Saturn in 1980 and 1981, we realized we couldn’t see through the atmosphere of Titan because we didn’t have the right filters,” Spilker said, as we chatted in her office at JPL. “So people started planning in the early 1980’s for a mission that would go back to Saturn, and to look at Titan.”

Wes Huntress, longtime JPL scientist and Director of NASA’s Solar System Exploration Division, was in charge of developing this new mission, and in 1988 he asked Spilker to be his deputy.

“This project ultimately became Cassini,” Spilker said. “It didn’t have a name yet and wasn’t funded at that time, but I’ve been with it ever since. Talk about longevity!”

Spilker added that the entire mission has been a “wonderful experience,” and that she has been fascinated by Saturn ever since she got a telescope when she was in 3rd grade.

Maize said one of the most memorable moments for him came early in the mission: orbit insertion at Saturn.

“That was the must-do event,” he said. “We had a 45-minute burn and we were either a flyby mission or we were in business. I was feeling pretty good about the burn, but what was amazing about it was that if the burn was completed properly, we were going to be able to get some amazing images as the spacecraft came up over the ring plane of the planet. I was sitting with Ed Weiler the next morning at about 4:30 a.m., looking at those images and it was just amazing. I’ll never forget it. It was probably the hallmark moment for me.”

At that time, no spacecraft had ever been that close to Saturn’s rings before. Now, as the mission enters the beginning of the final phase of the mission –as it prepares to plunge into the gas giant in 2017 to protect any potential life on any of Saturn’s moons from contamination from the spacecraft — it will come even closer to the rings, diving close and through Saturn’s rings a total of 20 times.

“It’s taken years of planning, but now that we’re finally here, the whole Cassini team is excited to begin studying the data that come from these ring-grazing orbits,” said Spilker. “This is a remarkable time in what’s already been a thrilling journey.”

What will Cassini’s legacy be? Spilker offered a unique perspective.

“The biggest legacy will be how it has helped us realize all the different possibilities of where life might be found, even within our own solar system,” she said. “We’ve found that you don’t necessarily need to have a planet in the sweet spot from a star, where you could have liquid water on the surface. That might change the way we look at exoplanets. Yes, let’s find those earths or super-earths in that sweet spot, but when our instruments improve, let’s look for those giant planets that might have moons that might have life. That has broadened our places to look. From Cassini, I think we’ve learned that maybe there’s a lot more possibility for life than we had ever imagined.”

“Incredible Stories From Space” takes readers behind the scenes of the unmanned missions that are transforming our understanding of the solar system and beyond. Weaving together one-on-one interviews along with the extraordinary sagas of the spacecraft themselves, this book chronicles the struggles and triumphs of nine current space missions and captures the true spirit of exploration and discovery. Look for more “stories” and an excerpt from the book as the release date of Dec. 20 approaches.