KENNEDY SPACE CENTER, FL – Monday’s (Dec. 12) planned launch of NASA’s innovative Cyclone Global Navigation Satellite System (CYGNSS) hurricane microsatellite fleet was aborted when a pump in the hydraulic system that releases the Pegasus air-launch booster from its L-1011 carrier aircraft failed in flight. UPDATE: launch delayed to Dec 15, story revised

NASA and Orbital ATK confirmed this afternoon that the launch of the Orbital ATK commercial Pegasus-XL rocket carrying the CYGNSS small satellite constellation has been rescheduled again to Thursday, Dec. 15 at 8:26 a.m. EST from a drop point over the Atlantic Ocean.

Late last night the launch was postponed another day from Dec. 14 to Dec. 15 to solve a flight parameter issue on the CYGNSS spacecraft. New software was uploaded to the spacecraft that corrected the issue, NASA officials said.

“NASA’s launch of CYGNSS spacecraft is targeted for Thursday, Dec. 15,” NASA announced.

“We are go for launch of our #Pegasus rocket carrying #CYGNSS tomorrow, December 15 from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station,” Orbital ATK announced.

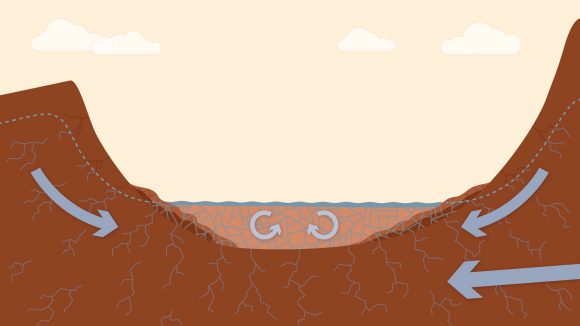

“The CYGNSS constellation consists of eight microsatellite observatories that will measure surface winds in and near a hurricane’s inner core, including regions beneath the eyewall and intense inner rainbands that previously could not be measured from space,” according to a NASA factsheet.

Despite valiant efforts by the flight crew to restore the hydraulic pump release system to operation as the L-1011 flew aloft near the Pegasus drop zone, they were unsuccessful before the launch window ended and the mission had to be scrubbed for the day by NASA Launch Director Tim Dunn.

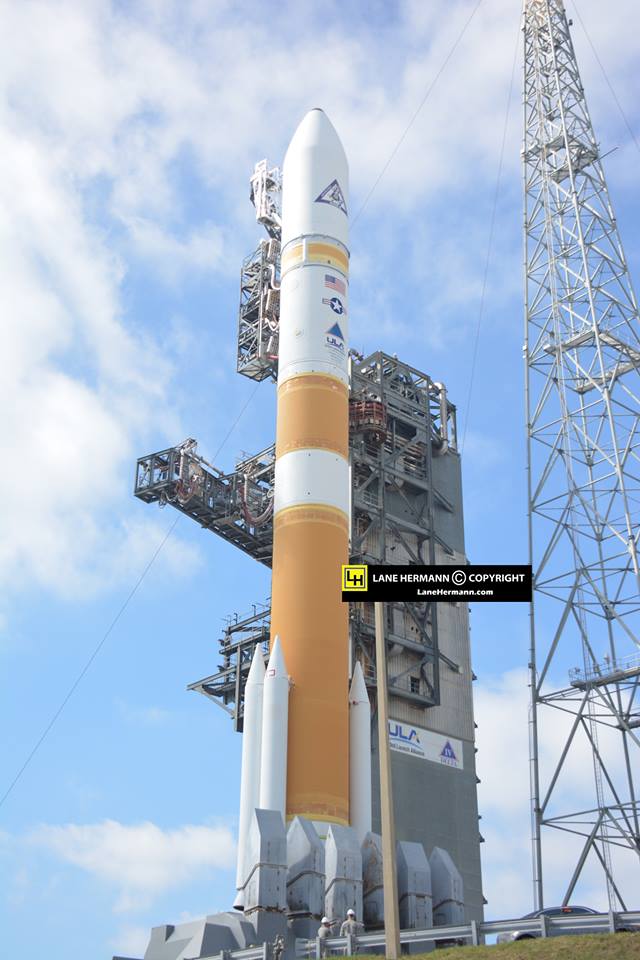

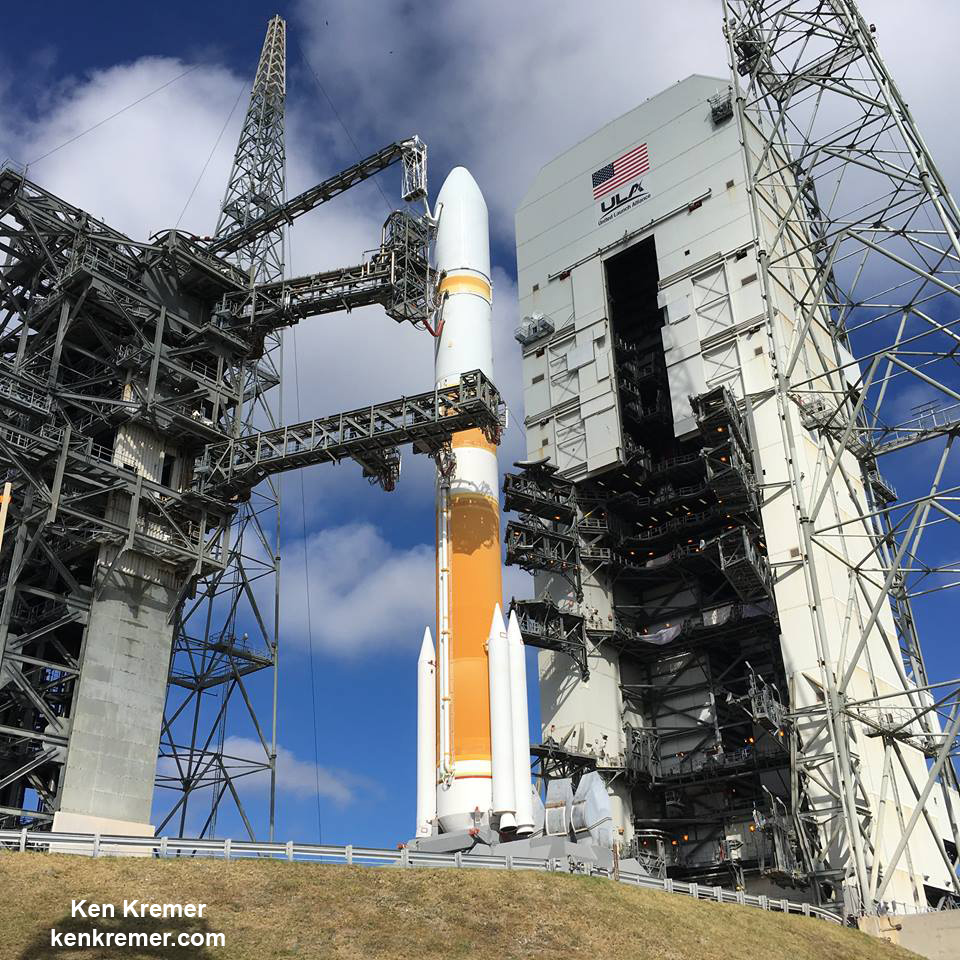

The Pegasus/CYGNSS vehicle is attached to the bottom of the Orbital ATK L-1011 Stargazer carrier aircraft.

The hydraulic release system passed its pre-flight checks before takeoff of the Stargazer.

“Launch of the Pegasus rocket was aborted due to an issue with the launch vehicle release on the L-1011 Stargazer. The hydraulic release system operates the mechanism that releases the Pegasus rocket from the carrier aircraft. The hydraulic system functioned properly during the pre-flight checks of the airplane,” said NASA.

A replacement hydraulic pump system component was flown in from Mojave, California, and successfully installed and checked out. Required crew rest requirements were also met.

The one-hour launch window opens at 8:20 a.m and the actual deployment of the rocket from the L-1011 Tristar is timed to occur 5 minutes into the window at 8:26 a.m.

NASA’s Pegasus/CYGNUS launch coverage and commentary will be carried live on NASA TV – beginning at 7 a.m. EDT

You can watch the launch live on NASA TV at – http://www.nasa.gov/nasatv

Live countdown coverage on NASA’s Launch Blog begins at 6:30 a.m. Dec. 15.

Coverage will include live updates as countdown milestones occur, as well as video clips highlighting launch preparations and the flight.

A prelaunch program by NASA EDGE will begin at 6 a.m.

NASA’s Kennedy Space Center is also providing live coverage on social media at:

http://www.twitter.com/NASAKennedy

https://www.facebook.com/NASAKennedy

Orbital ATK is also providing launch and mission update at:

twitter.com/OrbitalATK

The weather forecast from the Air Force’s 45th Weather Squadron at Cape Canaveral has significantly increased to predicting a 90% chance of favorable conditions on Thursday, Dec. 15.

The primary weather concerns are for flight cumulus clouds.

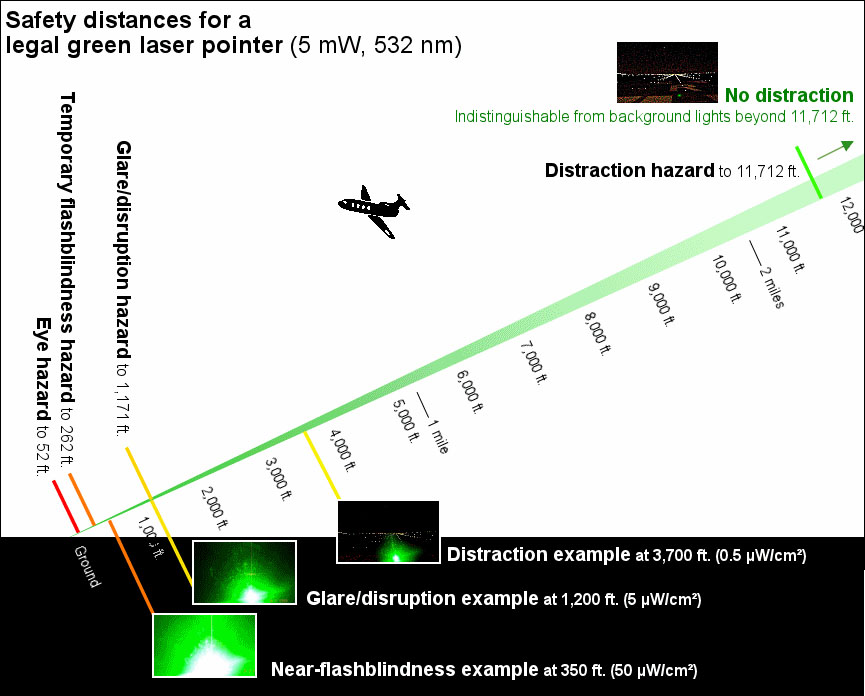

The Pegasus rocket cannot fly through rain or clouds due to a negative impact and possible damage on the rocket’s thermal protection system (TPS).

In the event of a delay, the range is also reserved for Friday, Dec. 16 where the daily outlook remains at a 90% chance of favorable weather conditions.

After Stargazer takes off from the Skid Strip early Thursday around 6:30 a.m. EST, it will fly north to a designated drop point box about 126 miles east of Daytona Beach, Florida over the Atlantic Ocean. The crew can search for a favorable launch point if needed, just as they did Monday morning.

The drop box point measures about 40-miles by 10-miles (64-kilometers by 16-kilometers). The flight crew flew through the drop box twice on Monday, about a half an hour apart, as they tried to repair the hydraulic system by repeatedly cycling it on and off and sending commands.

“It was not meeting the prescribed launch release pressures, indicating a problem with the hydraulic pump,” said NASA CYGNSS launch director Tim Dunn.

“Fortunately, we had a little bit of launch window to work with, so we did a lot of valiant troubleshooting in the air. As you can imagine, everyone wanted to preserve every opportunity to have another launch attempt today, so we did circle around the race once, resetting breakers on-board the aircraft, doing what we could in flight to try to get that system back into function again.”

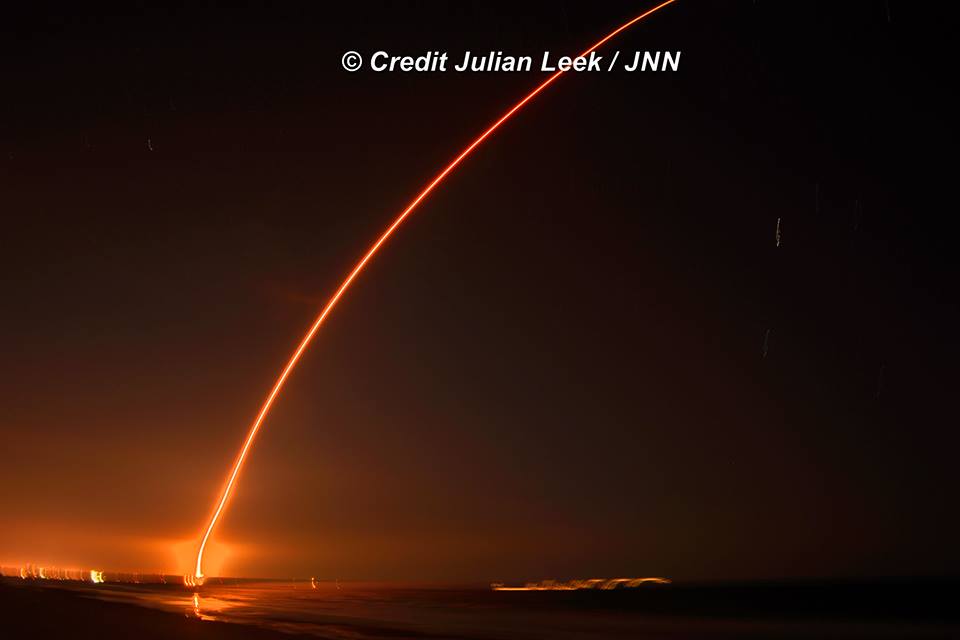

The rocket will be dropped for a short freefall of about 5 seconds to initiate the launch sewuence. It launches horizontally in midair with ignition of the first stage engine burn, and then tilts up to space to begin the trek to LEO.

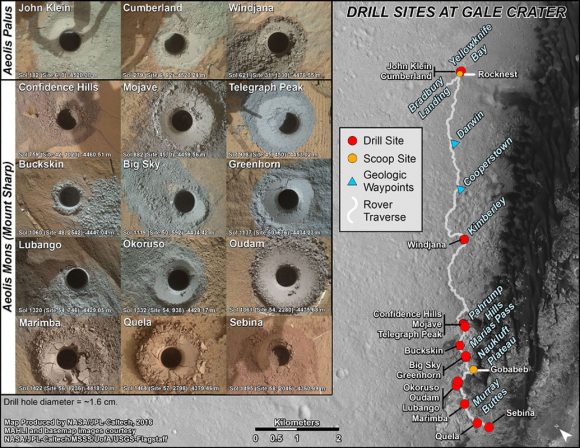

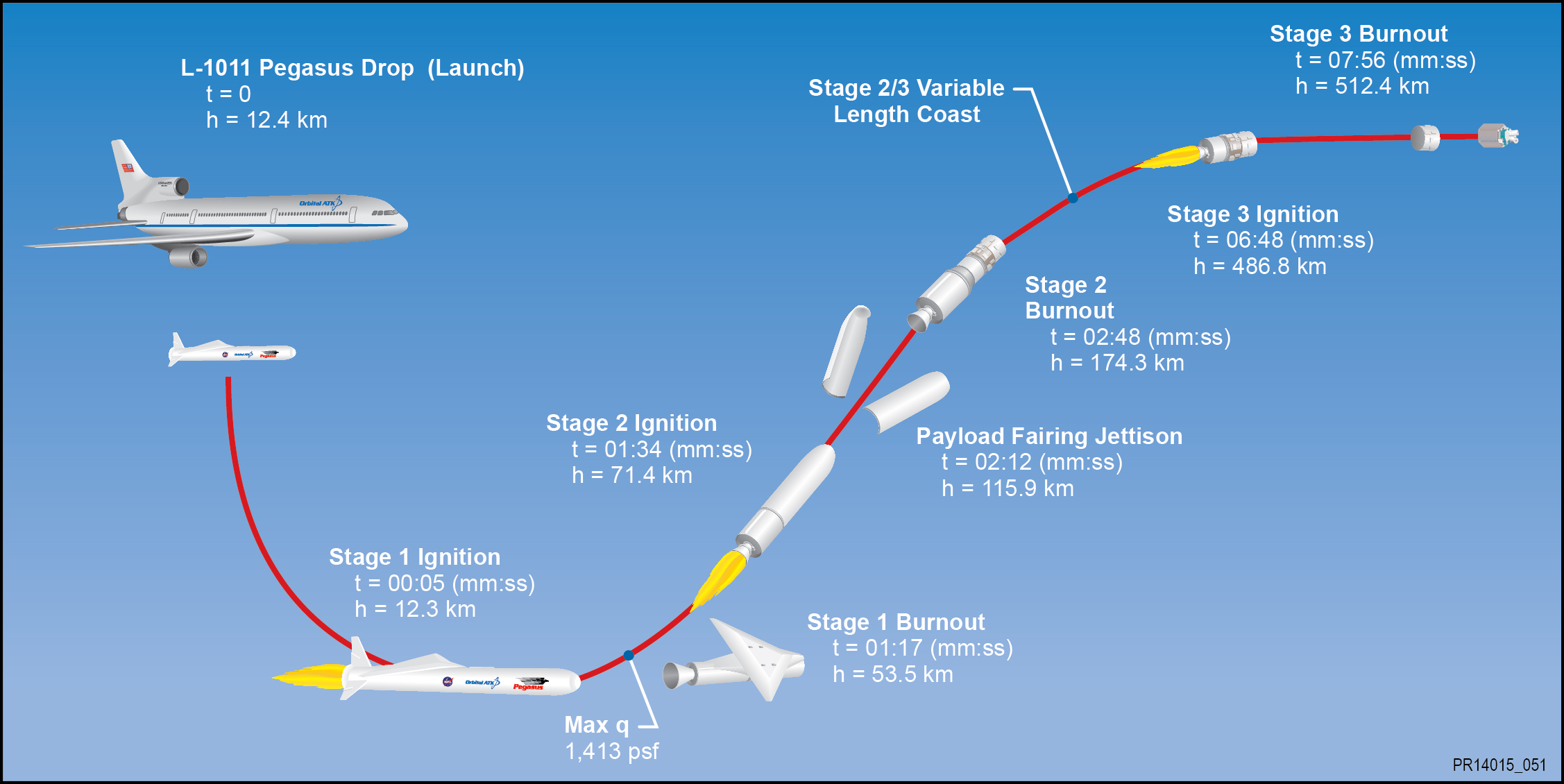

Here’s a schematic of key launch events:

The $157 million fleet of eight identical spacecraft comprising the Cyclone Global Navigation Satellite System (CYGNSS) system will be delivered to low Earth orbit by the Orbital ATK Pegasus XL rocket.

The nominal mission lifetime for CYGNSS is two years but the team says they could potentially last as long as five years or more if the spacecraft continue functioning.

Pegasus launches from the Florida Space Coast are infrequent. The last once took place over 13 years ago in April 2003 for the GALEX mission.

Typically they take place from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California or the Reagan Test Range on the Kwajalein Atoll.

CYGNSS counts as the 20th Pegasus mission for NASA.

The CYGNSS spacecraft were built by Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, Texas. Each one weighs approx 29 kg. The deployed solar panels measure 1.65 meters in length.

The solar panels measure 5 feet in length and will be deployed within about 15 minutes of launch.

The Space Physics Research Laboratory at the University of Michigan College of Engineering in Ann Arbor leads overall mission execution in partnership with the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, Texas.

The Climate and Space Sciences and Engineering Department at the University of Michigan leads the science investigation, and the Earth Science Division of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate oversees the mission.

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Earth and Planetary science and human spaceflight news.