Since ancient times, human beings have been staring at the night sky and been amazed by the celestial objects looking back at them. Whereas these objects were once thought to be divine in nature, and later mistaken for comets or other astrological phenomena, ongoing observation and improvements in instrumentation have led to these objects being identified for what they are.

For example, there are the Small and Large Magellanic Clouds, two large clouds of stars and gas that can be seen with the naked eye in the southern hemisphere. Located at a distance of 200,000 and 160,000 light years from the Milky Way Galaxy (respectively), the true nature of these objects has only been understand for about a century. And yet, these objects still have some mysteries that have yet to be solved.

Characteristics:

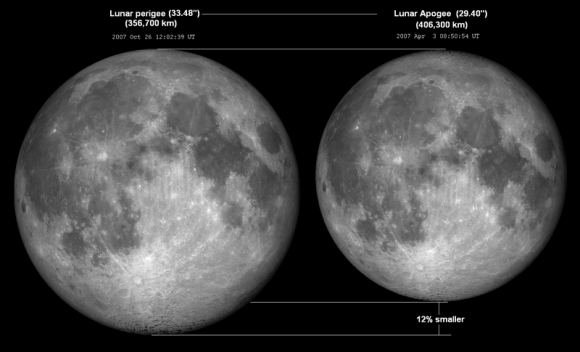

The Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC) and the neighboring the Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC) are starry regions that orbit our galaxy, and look conspicuously like detached pieces of the Milky Way. Though they are separated by 21 degrees in the night sky – about 42 times the width of the full moon – their true distance is about 75,000 light-years from each other.

The Large Magellanic Cloud is located about 160,000 light-years from the Milky Way, in the constellation Dorado. This makes it the 3rd closest galaxy to us, behind the Sagittarius Dwarf and Canis Major Dwarf galaxies. Meanwhile, the Small Magellanic Cloud is located in the constellation of Tucana, about 200,000 light-years away.

The LMC is roughly twice the diameter of the SMC, measuring some 14,000 light-years across vs. 7,000 light years (compared to 100,000 light years for the Milky Way). This makes it the 4th largest galaxy in our Local Group of galaxies, after the Milky Way, Andromeda and the Triangulum Galaxy. The LMC is about 10 billion times as massive as our Sun (about a tenth the mass of the Milky Way), while the SMC is equivalent to about 7 billion Solar Masses.

In terms of structure, astronomers have classified the LMC as an irregular type galaxy, but it does have a very prominent bar in its center. Ergo, it’s possible that it was a barred spiral before its gravitational interactions with the Milky Way. The SMC also contains a central bar structure and it is speculated that it too was once a barred spiral galaxy that was disrupted by the Milky Way to become somewhat irregular.

Aside from their different structure and lower mass, they differ from our galaxy in two major ways. First, they are gas-rich – meaning that a higher fraction of their mass is hydrogen and helium – and they have poor metallicity, (meaning their stars are less metal-rich than the Milky Way’s). Both possess nebulae and young stellar populations, but are made up of stars that range from very young to the very old.

In fact, this abundance in gas is what ensures that the Magellanic Clouds are able to create new stars, with some being only a few hundred million years in age. This is especially true of the LMC, which produces new stars in large quantities. A good example of this is it’s glowing-red Tarantula Nebula, a gigantic star-forming region that lies 160,000 light-years from Earth.

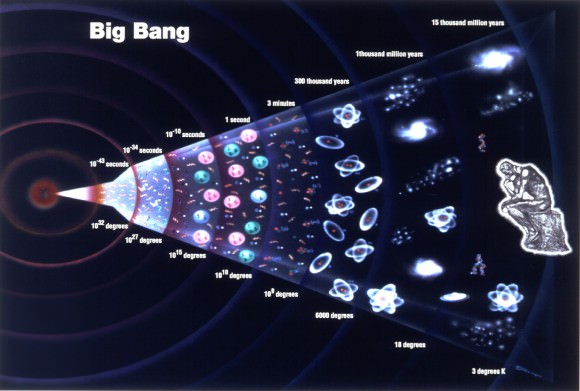

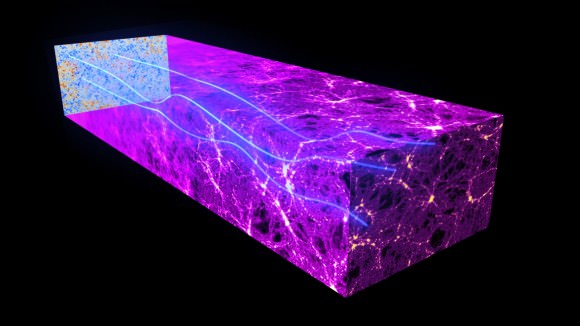

Astronomers estimate that the Magellanic Clouds were formed approximately 13 billion years ago, around the same time as the Milky Way Galaxy. It has also been believed for some time that the Magellanic Clouds have been orbiting the Milky Way at close to their current distances. However, observational and theoretical evidence suggests that the clouds have been greatly distorted by tidal interactions with the Milky Way as they travel close to it.

This indicates that they are not likely to have frequently got as close to the Milky Way as they are now. For instance, measurements conducted with the Hubble Space Telescope in 2006 suggested that the Magellanic Clouds may be moving too fast to be long terms companions of the Milky Way. In fact, their eccentric orbits around the Milky Way would seem to indicate that they came close to our galaxy only once since the universe began.

This was followed in 2010 by a study that indicated that the Magellanic Clouds may be passing clouds that were likely expelled from the Andromeda Galaxy in the past. The interactions between the Magellanic Clouds and the Milky Way is evidenced by their structure and the streams of neutral hydrogen that connects them. Their gravity has affected the Milky Way as well, distorting the outer parts of the galactic disk.

History of Observation:

In the southern hemisphere, the Magellanic clouds were a part of the lore and mythology of the native inhabitants, including the Australian Aborigines, the Maori of New Zealand, and the Polynesian people of the South Pacific. For the latter, they served as important navigational markers, while the Maori used them as predictors of the winds.

While the study Magellanic Clouds dates back to the 1st millennium BCE, the earliest surviving record comes from the 10th century Persian astronomer Al Sufi. In his 964 treatise, Book of Fixed Stars, he called the LMC al-Bakr (“the Sheep”) “of the southern Arabs”. He also noted that the Cloud is not visible from northern Arabia or Baghdad, but could be seen at the southernmost tip of Arabian Peninsula.

By the late 15th century, Europeans are believed to have become acquainted with the Magellanic Clouds thanks to exploration and trade missions that took them south of the equator. For instance, Portuguese and Dutch sailors came to know them as the Cape Clouds, since they could only be viewed when sailing around Cape Horn (South America) and the Cape of Good Hope (South Africa).

During the circumnavigation of the Earth by Ferdinand Magellan (1519–22), the Magellanic Clouds were described by Venetian Antonio Pigafetta (Magellan’s chronicler) as dim clusters of stars. In 1603, German celestial cartographer Johann Bayer published his celestial atlas Uranometria, where he named the smaller cloud “Nebecula Minor” (Latin for “Little Cloud”).

Between 1834 and 1838, English astronomer John Herschel conducted surveys of the southern skies from the Royal Observatory at the Cape of Good Hope. While observing the SMC, he described it as a cloudy mass of light with an oval shape and a bright center, and catalogued a concentration of 37 nebulae and clusters within it.

In 1891, the Harvard College Observatory opened an observing station in southern Peru. From 1893-1906, astronomers used the observatory’s 61 cm (24 inch) telescope to survey and photograph the LMC and SMC. One such astronomers was Henriette Swan Leavitt, who used the observatory to discover Cephied Variable stars in the SMC.

Her findings were published in 1908 a study titled “1777 variables in the Magellanic Clouds“, in which she showed the relationship between these star’s variability period and luminosity – which became a very reliable means of determining distance. This allowed the SMCs distance to be determined, and became the standard method of measuring the distance to other galaxies in the coming decades.

As noted already, in 2006, measurements made suing the Hubble Space Telescope were announced that suggested the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds may be moving too fast to be orbiting the Milky Way. This has given rise to the theory that they originated in another galaxy, most likely Andromeda, and were kicked out during a galactic merger.

Given their composition, these clouds – especially the LMC – will continue making new stars for some time to come. And eventually, millions of years from now, these clouds may merge with our own Milky Way Galaxy. Or, they could keep orbiting us, passing close enough to suck up hydrogen and keep their star-forming process going.

But in a few billion years, when the Andromeda Galaxy collides with our own, they may find themselves having no choice but to merge with the giant galaxy that results. One might say Andromeda regrets spitting them out, and is coming to collect them!

We have written many articles about the Magellanic Clouds for Universe Today. Here’s What is the Small Magellanic Cloud?, What is the Large Magellanic Cloud?, Stolen: Magellanic Clouds – Return to Andromeda, The Magellanic Clouds are Here for the First Time.

If you’d like more info on galaxies, check out Hubblesite’s News Releases on Galaxies, and here’s NASA’s Science Page on Galaxies.

We have also recorded an episode of Astronomy Cast about galaxies – Episode 97: Galaxies.

Sources: