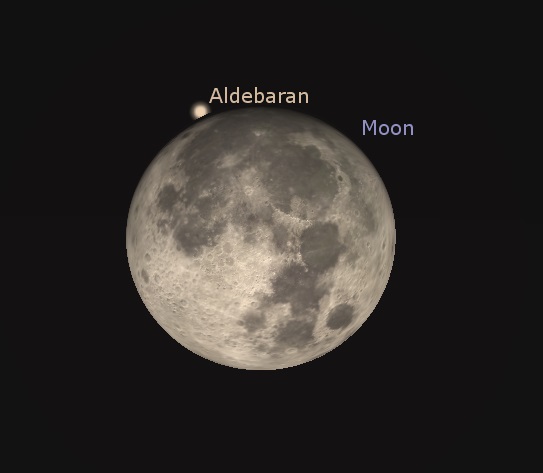

It’s a busy week for the Moon. While our large solitary natural satellite reaches Full and interferes with the 2016 Geminids, it’s also beginning a series of complex bright star occultations of Aldebaran and Regulus, giving us a taste of things to come in 2017.

First up, here’s the lowdown on this week’s occultation of Aldebaran by the Moon, coming right up tonight:

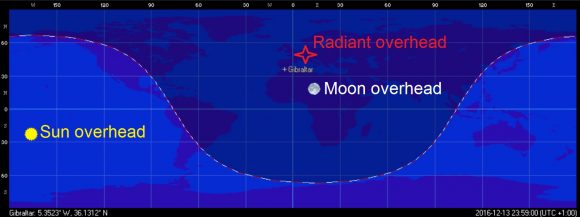

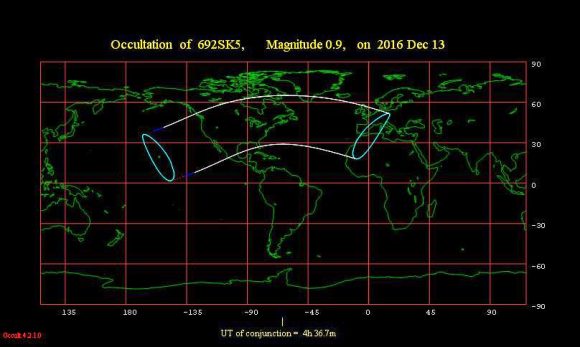

The 99% illuminated waxing gibbous Moon occults the +0.9 magnitude star Aldebaran on Monday, December 12th. The Moon is just 19 hours and 30 minutes before reaching Full during the event. Both are located 167 degrees east of the Sun at the time of the event. The central time of conjunction is 4:37 Universal Time (UT). The event occurs during the daylight hours over Hawaii at dusk during Moonrise, and under darkness for Mexico, most of Canada and the contiguous United States. The event also includes the United Kingdom and southwestern Europe at Moonset near early dawn. This is the final occultation of Aldebaran by the Moon for 2016; The Moon will next occult Aldebaran on January 9th, 2017. This is occultation 26 in the current series of 49, running from January 29th, 2015 to September 3rd, 2018.

Four 1st magnitude stars are along the Moon’s path in the current epoch: Regulus, Aldebaran, Antares and Spica. In the current century, (2001-2100 AD) the Moon occults Aldebaran 247 times, topped only by Antares (386 times) and barely beating out Spica (220 times). The Moon also occults Regulus 220 times this century, and occultations of Spica and Antares resume on May 2024 and July 2023, respectively.

And yes, this Supermoon 3 of 3 for 2016, though actual perigee occurs at 23:28 UT tonight, 39 minutes past our own ’24 hour from Full’ rule. The Moon reaches Full on Wednesday, December 14th at just past midnight at 00:07 UT. This is also the closest Full Moon to the December 21st winter solstice next week, and the Full Moon will ride high in the sky this week for northern hemisphere observers on long winter nights.

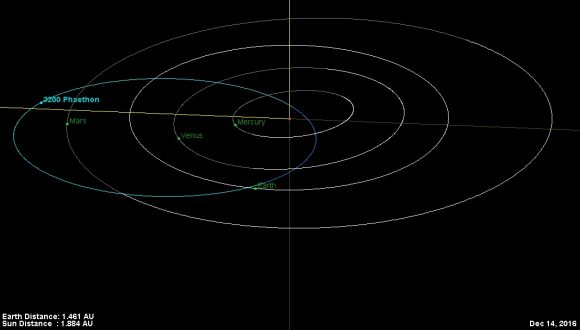

Keep an eye out for Geminid meteors tonight as well… sure, 2016 may be an off year for this usually spectacular shower, but a few brighter fireballs may still punch through the lunar light pollution.

Clouded out? Be sure to catch the Supermoon action tomorrow night live online starting at 16:00 UT, courtesy of Gianluca Masi and the Virtual Telescope Project.

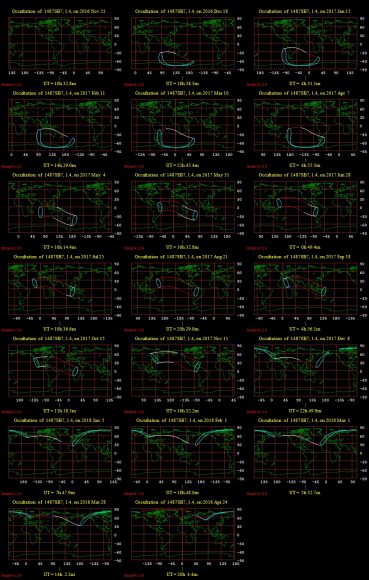

And there’s more. This coming weekend marks the start of an upcoming new cycle of occultations of Regulus by the Moon. These run right through 2018, as the Moon visits the bright star Regulus five days after crossing the Hyades and occulting Aldebaran for every lunation pass in 2017.

Here’s the specifics for Sunday’s event:

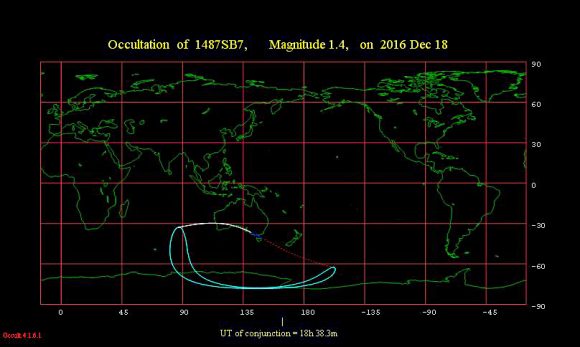

The 73% illuminated waning gibbous Moon occults the +1.4 magnitude star Regulus on Sunday, December 18th. The Moon is just four days past Full during the event. Both are located 117 degrees west of the Sun at the time of the event. The central time of conjunction is 18:38 Universal Time (UT). The event occurs during the daylight hours over Tasmania, and under darkness for the southwestern tip of Australia, including Perth. The Moon will next occult Regulus on January 15th, 2017. This is the first occultation in a new series of nineteen, running from this weekend to April 24th, 2018.

It’s worth noting that the graze line for Sunday’s occultation of Regulus by the Moon runs just north of the Australian city of Perth and the Perth Observatory… let us know if anyone ‘Down Under’ witnesses the first occultation of Regulus in the new cycle.

Can you spy Regulus’ white dwarf companion? Located 77 light years distant, the Regulus system has at least four components: a B/C pair shining at a combined magnitude of +8, with an apparent separation of 3”, (5,000 AU physical distance in a ~600 year orbit) and an unseen white dwarf companion in a tight 40 day orbit. We know that said white dwarf companion exists from spectroscopic analysis… and it would shine at an easy magnitude +13, were it not near dazzling Regulus shining over 10,000 times brighter. Could this elusive companion turn up just moments before the reappearance of Regulus from behind the Moon? Remember, the dark limb of the Moon leads the way during waxing phases, then trails as the Moon wanes. These and other amazing facts are included in our forthcoming free guide to 101 Astronomical Events to watch out for in 2017.

Follow that Moon, and don’t miss these fine astro-events coming to sky above you this week!