By Andy Tomaswick

March 14, 2025

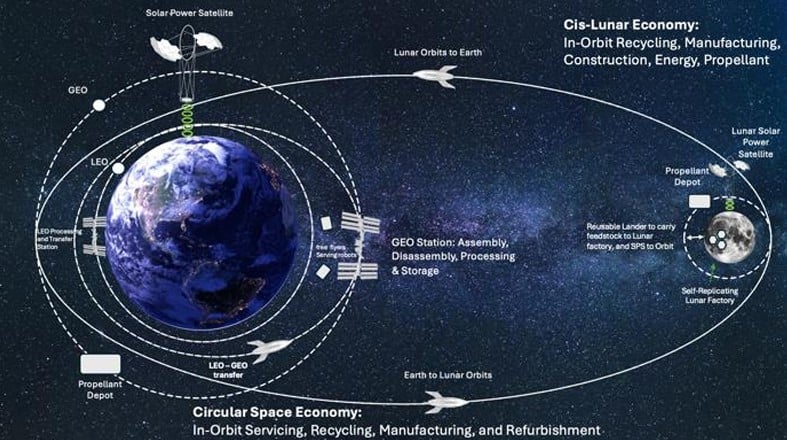

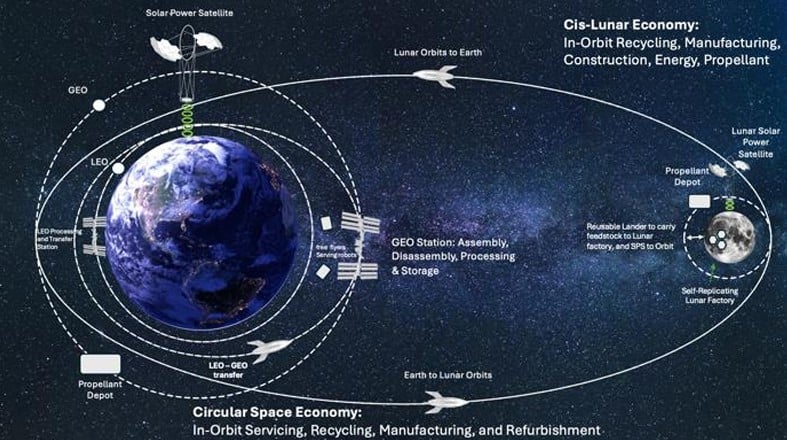

Solar Power Satellite (SPS) advocates have been dreaming of using space resources to build massive constructions for decades. In-space Resource Utilization (ISRU) advocates would love to oblige them, but so far, there hasn't yet been enough development on either front to create a testable system. A research team from a company called MetaSat and the University of Glasgow hope to change that with a new plan called META-LUNA, which utilizes lunar resources to build (and recycle) a fleet of their specially designed SPS.

Continue reading

By Matthew Williams

March 13, 2025

The Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) has announced the science objectives for Webb's General Observer Programs in Cycle 4 (Cycle 4 GO) program. The Cycle 4 observations include 274 programs that establish the science program for JWST's fourth year of operations, amounting to 8,500 hours of prime observing time. This is a significant increase from Cycle 3 observations and the 5,500 hours of prime time and 1,000 hours of parallel time it entailed.

Continue reading

By David Dickinson

March 13, 2025

A distant trio of worlds may shed light on planetary formation in the early solar system.

Sometimes, good things come in threes. If astronomers are correct, a system in the distant Kuiper Belt may not be two but three worlds, offering an insight into formation in the early solar system.

The study comes out of researchers at Brigham Young University and the Space Telescope Science Institute.

Continue reading

By Mark Thompson

March 13, 2025

The increasing frequency of so-called ‘1-in-a-1000-year' weather events highlights how global warming is disrupting rather more typical weather patterns beyond what scientific models can reliably predict. A recent paper proposes a three-tier scientific approach for addressing these unprecedented climate challenges: improving rapid response capabilities, making incremental infrastructure adaptations, and pursuing transformational system changes to manage escalating climate chaos.

Continue reading

By Evan Gough

March 13, 2025

Many sci-fi plots revolve around alien life reaching Earth and causing problems. In "Invasion of the Body Snatchers," alien pods arrive on Earth and replace humans.

Continue reading

By Andy Tomaswick

March 13, 2025

CubeSats have a lot of advantages. They are small, inexpensive, and easily reproducible. But those advantages also come with significant disadvantages - they have trouble linking into broader constellations that allow them to be more effective at their observational or communication tasks. A team from the University of Albany thinks they might have solved that problem by using a customized calibration algorithm to ensure the right CubeSats link up together.

Continue reading

By Mark Thompson

March 13, 2025

Located on a mountaintop in Chile, the nearly complete Vera C. Rubin Observatory will capture the Universe in incredible detail. This week saw another huge step for the observatory with the installation of the car sized - yes car sized - LSST camera onto the Simonyi Survey Telescope. The camera is the largest ever built, weighing in at over 3,000 kilograms with an impressive 3,200 megapixels. Coupled to the 8.4 metre optics of the Rubin will allow it to capture everything that happens in the southern sky, night after night.

Continue reading

By Mark Thompson

March 13, 2025

On March 11, the California skyline was once again treated to the launch of the SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket from the Vandenberg Space Force Base. It carried two missions into space; SPHEREx to study the origins of the Universe and the molecular clouds of the Milky Way and four other satellites making up PUNCH. This latter mission is tasked with exploring how the Sun’s outer atmosphere causes the solar wind.

Continue reading

By Andy Tomaswick

March 13, 2025

Electrolysis has been a mainstay of crewed mission designs for the outer solar system for decades. It is the most commonly used methodology to split oxygen from water, creating a necessary gas from a necessary liquid. However, electrolysis systems are bulky and power-intensive, so NASA has decided to look into alternative solutions. They supported a company called Precision Combustion, Inc (PCI) via their Institutes for Advanced Concepts (NIAC) grant to work on a system of thermo-photo-catalytic conversion that could dramatically outperform existing electrolysis reactors.

Continue reading

By Mark Thompson

March 13, 2025

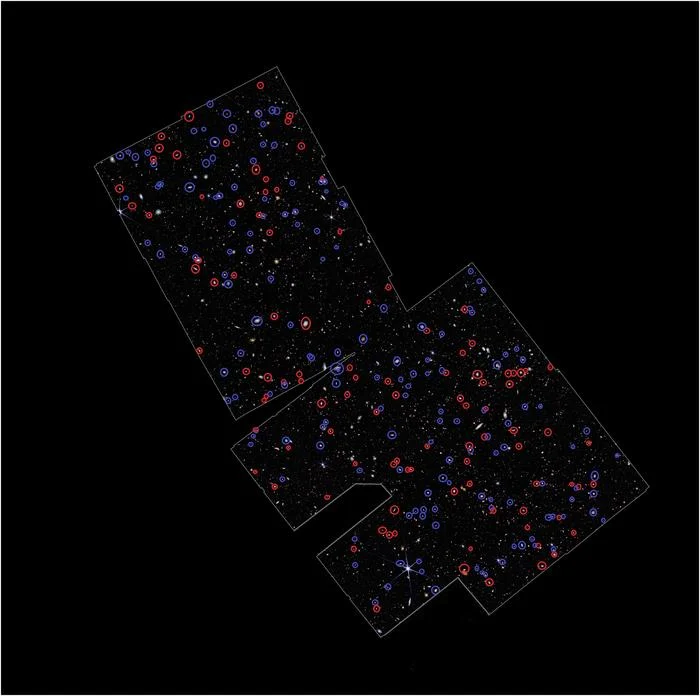

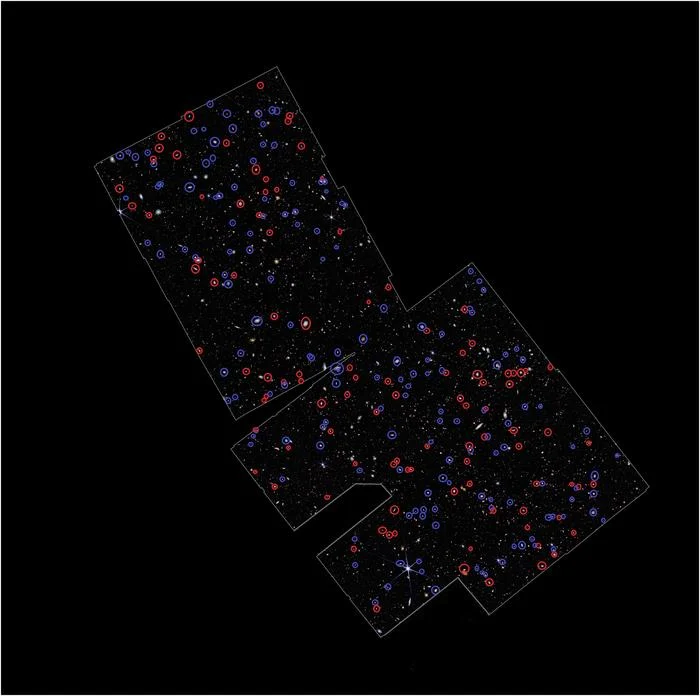

Astronomers using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) have completed a survey of galaxies that reveals their rotation directions with unprecedented clarity. Contrary to expectations that galaxy rotations would be randomly distributed, they discovered a surprising pattern, that most galaxies appear to rotate in a similar direction! One hypothesis suggests the universe itself might have an overall rotation, researchers believe a more plausible explanation though is that Earth's motion through space creates an observational bias, making galaxies rotating in certain directions more detectable than others.

Continue reading

Universe Today

Universe Today