Hundreds of millions of light years away, a supermassive black hole sits in the center of a galaxy cluster named Ophiuchus. Though black holes are renowned for sucking in surrounding material, they sometimes expel material in jets. This black hole is the site of an almost unimaginably powerful explosion, created when an enormous amount of material was expelled.

Continue reading “Astronomers Have Recorded the Biggest Explosion Ever Seen in the Universe”New Method for Researching Activity Around Quasars and Black Holes

Ever since the discovery of Sagittarius A* at the center of our galaxy, astronomers have come to understand that most massive galaxies have a Supermassive Black Hole (SMBH) at their core. These are evidenced by the powerful electromagnetic emissions produced at the nuclei of these galaxies – which are known as “Active Galatic Nuclei” (AGN) – that are believed to be caused by gas and dust accreting onto the SMBH.

For decades, astronomers have been studying the light coming from AGNs to determine how large and massive their black holes are. This has been difficult, since this light is subject to the Doppler effect, which causes its spectral lines to broaden. But thanks to a new model developed by researchers from China and the US, astronomers may be able to study these Broad Line Regions (BLRs) and make more accurate estimates about the mass of black holes.

The study, “Tidally disrupted dusty clumps as the origin of broad emission lines in active galactic nuclei“, recently appeared in the scientific journal Nature. The study was led by Jian-Min Wang, a researcher from the Institute of High Energy Physics (IHEP) at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, with assistance from the University of Wyoming and the University of Nanjing.

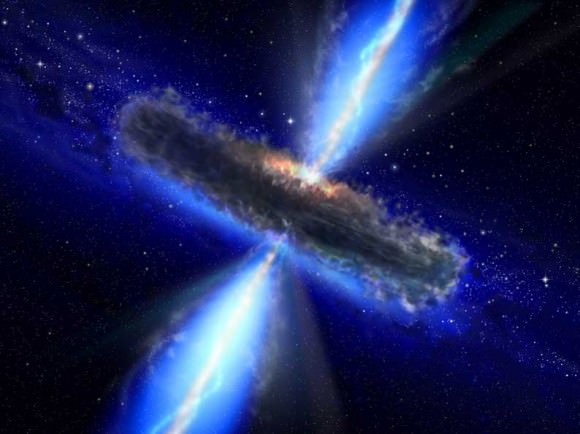

To break it down, SMBHs are known for having a torus of gas and dust that surrounds them. The black hole’s gravity accelerates gas in this torus to velocities of thousands of kilometers per second, which causes it to heat up and emit radiation at different wavelengths. This energy eventually outshined the entire surrounding galaxy, which is what allows astronomers to determine the presence of an SMBH.

As Michael Brotherton, a UW professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy and a co0author on the study, explained in a UW press release:

“People think, ‘It’s a black hole. Why is it so bright?’ A black hole is still dark. The discs reach such high temperatures that they put out radiation across the electromagnetic spectrum, which includes gamma rays, X-rays, UV, infrared and radio waves. The black hole and surrounding accreting gas the black hole is feeding on is fuel that turns on the quasar.”

The problem with observing these bright regions comes from the fact that the gases within them are moving so quickly in different directions. Whereas gas moving away (relative to us) is shifted towards the red end of the spectrum, gas that is moving towards us is shifted towards the blue end. This is what leads to a Broad Line Region, where the spectrum of the emitted light becomes more like a spiral, making accurate readings difficult to obtain.

Currently, the measurement of the mass of SMBHs in active galactic nuclei relies the “reverberation mapping technique”. In short, this involves using computer models to examine the symmetrical spectral lines of a BLR and measuring the time delays between them. These lines are believed to arise from gas that has been photoionized by the gravitational force of the SMBH.

However, since there is little understanding of broad emission lines and the different components of BLRs, this method gives rise to some uncertainties off between 200 and 300%. “We are trying to get at more detailed questions about spectral broad-line regions that help us diagnose the black hole mass,” said Brotherton. “People don’t know where these broad emission line regions come from or the nature of this gas.”

In contrast, the team led by Dr. Wang adopted a new type of computer model that considered the dynamics of the gas torus surrounding a SMBH. This torus, they assume, would be made up of discrete clumps of matter that would be tidally disrupted by the black hole, resulting in some gas flowing into it (aka. accreting on it) and some being ejected as outflow.

From this, they found that the emission lines in a BLR are subject to three characteristics – “asymmetry”, “shape” and “shift”. After examining various emissions lines – both symmetrical and asymmetrical – they found that these three characteristics were strongly dependent on how bright the gas clumps were, which they interpreted as being a result of the angle of their motion within the torus. Or as Dr. Brotherton put it:

“What we propose happens is these dusty clumps are moving. Some bang into each other and merge, and change velocity. Maybe they move into the quasar, where the black hole lives. Some of the clumps spin in from the broad-line region. Some get kicked out.”

Credit: NRAO/AUI/NSF

In the end, their new model suggests that tidally disrupted clumps of matter from a black hole torus may represent the source of the BLR gas. Compared to previous models, the one devised by Dr. Wang and his colleagues establishes a connection between different key processes and components in the vicinity of a SMBH. These include the feeding of the black hole, the source of photoionized gas, and the dusty torus itself.

While this research does not resolve all the mysteries surrounding AGNs, it is an important step towards obtaining accurate mass estimates of SMBHs based on their spectral lines. From these, astronomers could be able to more accurately determine what role these black holes played in the evolution of large galaxies.

The study was made possible thanks with support provided by the National Key Program for Science and Technology Research and Development, and the Key Research Program of Frontier Sciences, both of which are administered by the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

What are Active Galactic Nuclei?

In the 1970s, astronomers became aware of a compact radio source at the center of the Milky Way Galaxy – which they named Sagittarius A. After many decades of observation and mounting evidence, it was theorized that the source of these radio emissions was in fact a supermassive black hole (SMBH). Since that time, astronomers have come to theorize that SMBHs at the heart of every large galaxy in the Universe.

Most of the time, these black holes are quiet and invisible, thus being impossible to observe directly. But during the times when material is falling into their massive maws, they blaze with radiation, putting out more light than the rest of the galaxy combined. These bright centers are what is known as Active Galactic Nuclei, and are the strongest proof for the existence of SMBHs.

Description:

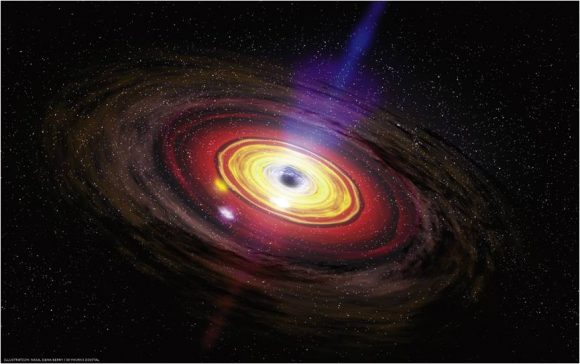

It should be noted that the enormous bursts in luminosity observed from Active Galactic Nuclei (AGNs) are not coming from the supermassive black holes themselves. For some time, scientists have understood that nothing, not even light, can escape the Event Horizon of a black hole.

Instead, the massive burst of radiations – which includes emissions in the radio, microwave, infrared, optical, ultra-violet (UV), X-ray and gamma ray wavebands – are coming from cold matter (gas and dust) that surround the black holes. These form accretion disks that orbit the supermassive black holes, and gradually feeding them matter.

The incredible force of gravity in this region compresses the disk’s material until it reaches millions of degrees kelvin. This generates bright radiation, producing electromagnetic energy that peaks in the optical-UV waveband. A corona of hot material forms above the accretion disc as well, and can scatter photons up to X-ray energies.

A large fraction of the AGN’s radiation may be obscured by interstellar gas and dust close to the accretion disc, but this will likely be re-radiated at the infrared waveband. As such, most (if not all) of the electromagnetic spectrum is produced through the interaction of cold matter with SMBHs.

The interaction between the supermassive black hole’s rotating magnetic field and the accretion disk also creates powerful magnetic jets that fire material above and below the black hole at relativistic speeds (i.e. a significant fraction of the speed of light). These jets can extend for hundreds of thousands of light-years, and are a second potential source of observed radiation.

Types of AGN:

Typically, scientists divide AGN into two categories, which are referred to as “radio-quiet” and “radio-loud” nuclei. The radio-loud category corresponds to AGNs that have radio emissions produced by both the accretion disk and the jets. Radio-quiet AGNs are simpler, in that any jet or jet-related emission are negligible.

Carl Seyfert discovered the first class of AGN in 1943, which is why they now bear his name. “Seyfert galaxies” are a type of radio-quiet AGN that are known for their emission lines, and are subdivided into two categories based on them. Type 1 Seyfert galaxies have both narrow and broadened optical emissions lines, which imply the existence of clouds of high density gas, as well as gas velocities of between 1000 – 5000 km/s near the nucleus.

Type 2 Seyferts, in contrast, have narrow emissions lines only. These narrow lines are caused by low density gas clouds that are at greater distances from the nucleus, and gas velocities of about 500 to 1000 km/s. As well as Seyferts, other sub classes of radio-quiet galaxies include radio-quiet quasars and LINERs.

Low Ionisation Nuclear Emission-line Region galaxies (LINERs) are very similar to Seyfert 2 galaxies, except for their low ionization lines (as the name suggests), which are quite strong. They are the lowest-luminosity AGN in existence, and it is often wondered if they are in fact powered by accretion on to a supermassive black hole.

Radio-loud galaxies can also be subdivded into categories like radio galaxies, quasars, and blazars. As the name suggests, radio galaxies are elliptical galaxies that are strong emitters of radiowaves. Quasars are the most luminous type of AGN, which have spectra similar to Seyferts.

However, they are different in that their stellar absorption features are weak or absent (meaning they are likely less dense in terms of gas) and the narrow emission lines are weaker than the broad lines seen in Seyferts. Blazars are a highly variable class of AGN that are radio sources, but do not display emission lines in their spectra.

Detection:

Historically speaking, a number of features have been observed within the centers of galaxies that have allowed for them to be identified as AGNs. For instance, whenever the accretion disk can be seen directly, nuclear-optical emissions can be seen. Whenever the accretion disk is obscured by gas and dust close to the nucleus, an AGN can be detected by its infra-red emissions.

Then there are the broad and narrow optical emission lines that are associated with different types of AGN. In the former case, they are produced whenever cold material is close to the black hole, and are the result of the emitting material revolving around the black hole with high speeds (causing a range of Doppler shifts of the emitted photons). In the former case, more distant cold material is the culprit, resulting in narrower emission lines.

Next up, there are radio continuum and x-ray continuum emissions. Whereas radio emissions are always the result of the jet, x-ray emissions can arise from either the jet or the hot corona, where electromagnetic radiation is scattered. Last, there are x-ray line emissions, which occur when x-ray emissions illuminate the cold heavy material that lies between it and the nucleus.

These signs, alone or in combination, have led astronomers to make numerous detections at the center of galaxies, as well as to discern the different types of active nuclei out there.

The Milky Way Galaxy:

In the case of the Milky Way, ongoing observation has revealed that the amount of material accreted onto Sagitarrius A is consistent with an inactive galactic nucleus. It has been theorized that it had an active nucleus in the past, but has since transitioned into a radio-quiet phase. However, it has also been theorized that it might become active again in a few million (or billion) years.

When the Andromeda Galaxy merges with our own in a few billion years, the supermassive black hole that is at its center will merge with our own, producing a much more massive and powerful one. At this point, the nucleus of the resulting galaxy – the Milkdromeda (Andrilky) Galaxy, perhaps? – will certainly have enough material for it to be active.

The discovery of active galactic nuclei has allowed astronomers to group together several different classes of galaxies. It’s also allowed astronomers to understand how a galaxy’s size can be discerned by the behavior at its core. And last, it has also helped astronomers to understand which galaxies have undergone mergers in the past, and what could be coming for our own someday.

We have written many articles about galaxies for Universe Today. Here’s What Fuels the Engine of a Supermassive Black Hole?, Could the Milky Way Become a Black Hole?, What is a Supermassive Black Hole?, Turning on a Supermassive Black Hole, What Happens when Supermassive Black Holes Collide?.

For more information, check out Hubblesite’s News Releases on Galaxies, and here’s NASA’s Science Page on Galaxies.

Astronomy Cast also has episodes about galactic nuclei and supermassive black holes. Here’s Episode 97: Galaxies and Episode 213: Supermassive Black Holes.

Source:

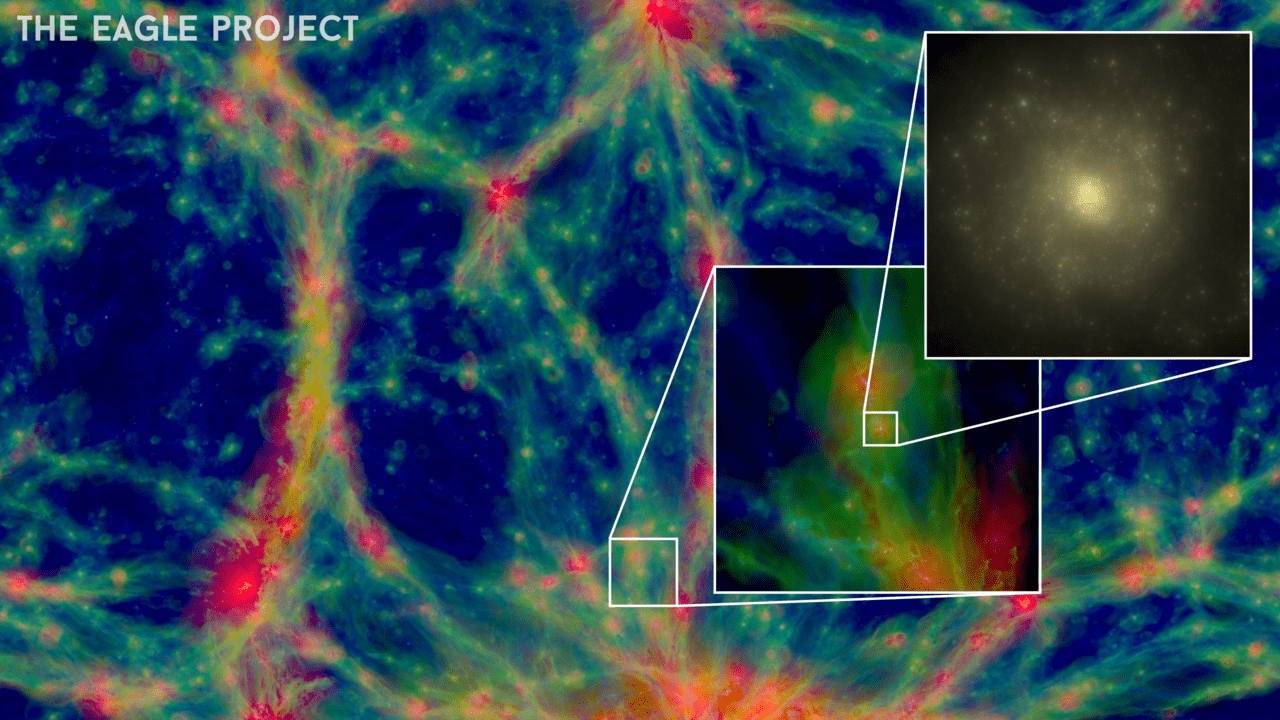

New Simulation Models Galaxies Like Never Before

Astronomy is, by definition, intangible. Traditional laboratory-style experiments that utilize variables and control groups are of little use to the scientists who spend their careers analyzing the intricacies our Universe. Instead, astronomers rely on simulations – robust, mathematically-driven facsimiles of the cosmos – to investigate the long-term evolution of objects like stars, black holes, and galaxies. Now, a team of European researchers has broken new ground with their development of the EAGLE project: a simulation that, due to its high level of agreement between theory and observation, can be used to probe the earliest epochs of galaxy formation, over 13 billion years ago.

The EAGLE project, which stands for Evolution and Assembly of GaLaxies and their Environments, owes much of its increased accuracy to the better modeling of galactic winds. Galactic winds are powerful streams of charged particles that “blow” out of galaxies as a result of high-energy processes like star formation, supernova explosions, and the regurgitation of material by active galactic nuclei (the supermassive black holes that lie at the heart of most galaxies). These mighty winds tend to carry gas and dust out of the galaxy, leaving less material for continued star formation and overall growth.

Previous simulations were problematic for researchers because they produced galaxies that were far older and more massive than those that astronomers see today; however, EAGLE’s simulation of strong galactic winds fixes these anomalies. By accounting for characteristic, high-speed ejections of gas and dust over time, researchers found that younger and lighter galaxies naturally emerged.

After running the simulation on two European supercomputers, the Cosmology Machine at Durham University in England and Curie in France, the researchers concluded that the EAGLE project was a success. Indeed, the galaxies produced by EAGLE look just like those that astronomers expect to see when they look to the night sky. Richard Bower, a member of the team from Durham, raved, “The universe generated by the computer is just like the real thing. There are galaxies everywhere, with all the shapes, sizes and colours I’ve seen with the world’s largest telescopes. It is incredible.”

The upshots of this new work are not limited to scientists alone; you, too, can explore the Universe with EAGLE by downloading the team’s Cosmic Universe app. Videos of the EAGLE project’s simulations are also available on the team’s website.

A paper detailing the team’s work is published in the January 1 issue of Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. A preprint of the results is available on the ArXiv.

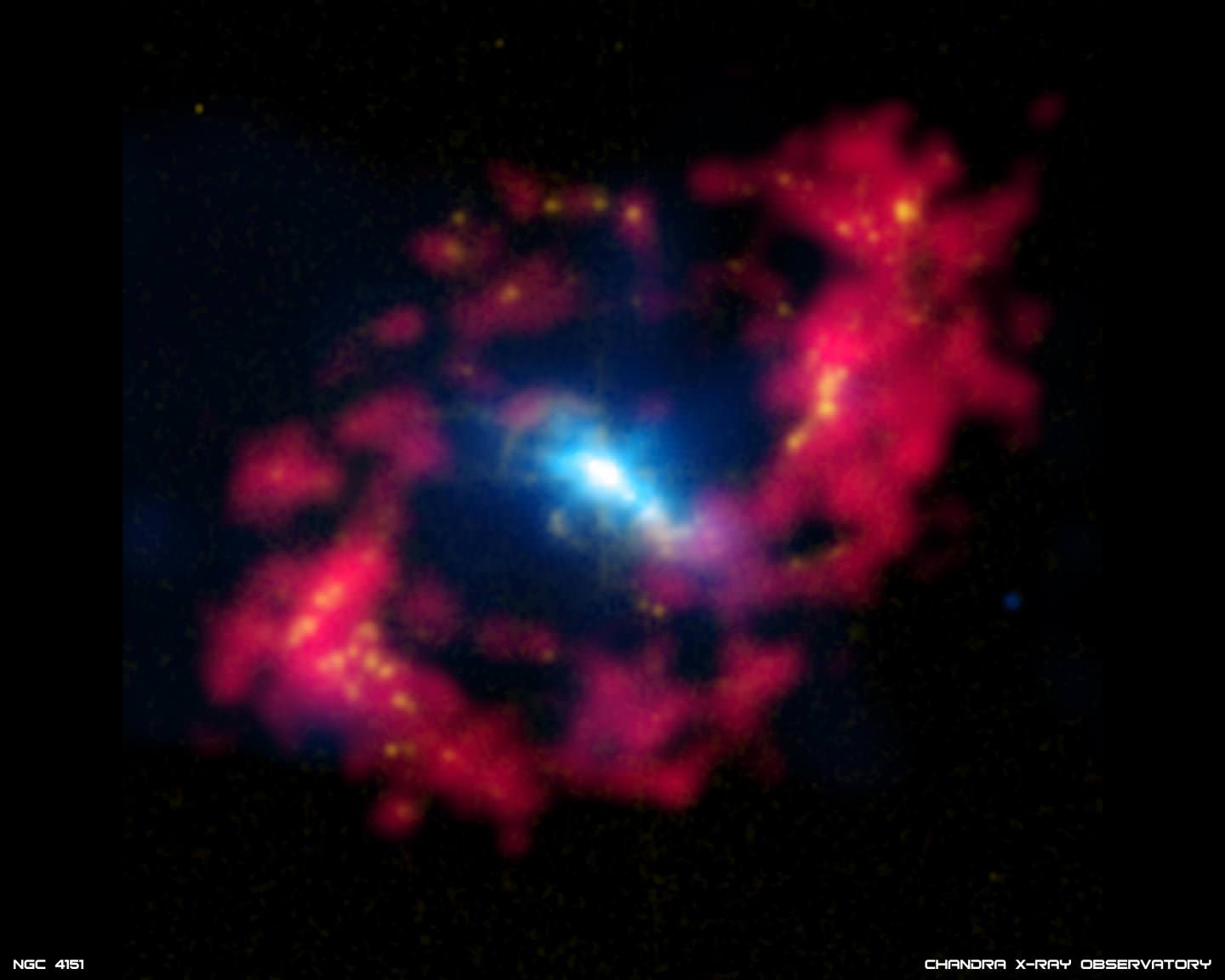

“Eye of Sauron” Galaxy Used For New Method of Galactic Surveying

Determining the distance of galaxies from our Solar System is a tricky business. Knowing just how far other galaxies are in relation to our own is not only key to understanding the size of the universe, but its age as well. In the past, this process relied on finding stars in other galaxies whose absolute light output was measurable. By gauging the brightness of these stars, scientists have been able to survey certain galaxies that lie 300 million light years from us.

However, a new and more accurate method has been developed, thanks to a team of scientists led by Dr. Sebastian Hoenig from the University of Southampton. Similar to what land surveyors use here on Earth, they measured the physical and angular (or apparent) size of a standard ruler in the galaxy to calibrate distance measurements.

Hoenig and his team used this method at the W. M. Keck Observatory, near the summit of Mauna Kea in Hawaii, to accurately determine for the first time the distance to the NGC 4151 galaxy – otherwise known to astronomers as the “Eye of Sauron”. Continue reading ““Eye of Sauron” Galaxy Used For New Method of Galactic Surveying”

When do Black Holes Become Active? The Case of the Strangely-Shaped Galaxy Mrk 273

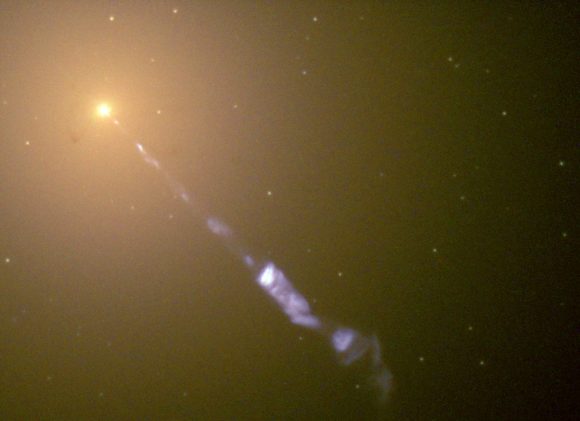

The Hubble image above shows a strange galaxy, known as Mrk 273. The odd shape – including the infrared bright center and the long tail extending into space for 130 thousand light-years – is strongly indicative of a merger between galaxies.

Near-infrared observations have revealed a nucleus with multiple components, but for years the details of such a sight have remained obscured by dust. With further data from the Keck Telescope, based in Hawaii, astronomers have verified that this object is the result of a merger between galaxies, with the infrared bright center consisting of two active galactic nuclei – intensely luminous cores powered by supermassive black holes.

At the center of every single galaxy is a supermassive black hole. While the name sounds exciting, our supermassive black hole, Sgr A* is pretty quiescent. But at the center of every early galaxy looms the opposite: an active galactic nuclei (AGN for short). There are plenty of AGN in the nearby Universe as well, but the question stands: how and when do these black holes become active?

In order to find the answer astronomers are looking at merging galaxies. When two galaxies collide, the supermassive black holes fall toward the center of the merged galaxy, resulting in a binary black hole system. At this stage they remain quiescent black holes, but are likely to become active soon.

“The accretion of material onto a quiescent black hole at the center of a galaxy will enable it to grow in size, leading to the event where the nucleus is “turned on” and becomes active,” Dr. Vivian U, lead author on the study, told Universe Today. “Since galaxy interaction provides means for gaseous material in the progenitor galaxies to lose angular momentum and funnels toward the center of the system, it is thought to play a role in triggering AGN. However, it has been difficult to pinpoint exactly how and when in a merging system this triggering occurs.”

While it has been known that an AGN can “turn on” before the final coalescence of the two black holes, it is unknown as to when this will happen. Quite a few systems do not host dual AGN. For those that do, we do not know whether synchronous ignition occurs or not.

Mrk 273 provides a powerful example to study. The team used near-infrared instruments on the Keck Telescope in order to probe past the dust. Adaptive optics also removed the blurring affects caused by the Earth’s atmosphere, allowing for a much cleaner image – matching the Hubble Space Telescope, from the ground.

“The punch line is that Mrk 273, an advanced late-stage galaxy merger system, hosts two nuclei from the progenitor galaxies that have yet to fully coalesce,” explains Dr. U. The presence of two supermassive black holes can be easily discerned from the rapidly rotating gas disks that surround the two nuclei.

“Both nuclei have already been turned on as evidenced by collimated outflows (a typical AGN signature) that we observe” Dr. U told me. Such a high amount of energy released from both supermassive black holes suggests that Mrk 273 is a dual AGN system. These exciting results mark a crucial step in understanding how galaxy mergers may “turn on” a supermassive black hole.

The team has collected near-infrared data for a large sample of galaxy mergers at different merging states. With the new data set, Dr. U aims “to understand how the nature of the nuclear star formation and AGN activity may change as a galaxy system progresses through the interaction.”

The results will be published in the Astrophysical Journal (preprint available here).

Galactic Mergers Fail to Feed Black Holes

[/caption]

The large black holes that reside at the center of galaxies can be hungry beasts. As dust and gas are forced into the vicinity around the black holes, it crowds up and jostles together, emitting lots of heat and light. But what forces that gas and dust the last few light years into the maw of these supermassive black holes?

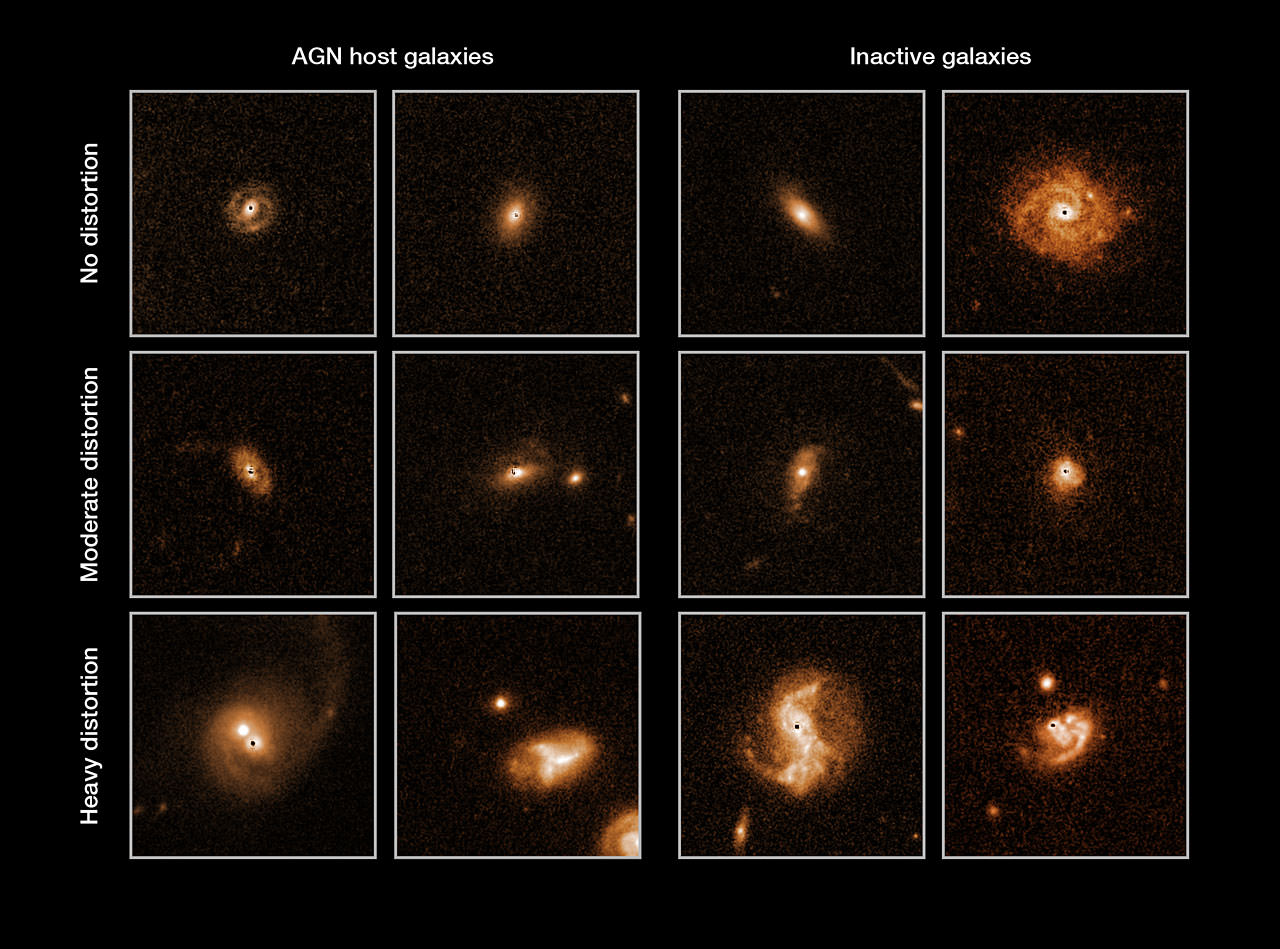

It has been theorized that mergers between galaxies disturbs the gas and dust in a galaxy, and forces the matter into the immediate neighborhood of the black hole. That is, until a recent study of 140 galaxies hosting Active Galactic Nuclei (AGN) – another name for active black holes at the center of galaxies – provided strong evidence that many of the galaxies containing these AGN show no signs of past mergers.

The study was performed by an international team of astronomers. Mauricio Cisternas of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy and his team used data from 140 galaxies that were imaged by the XMM-Newton X-ray observatory. The galaxies they sampled had a redshift between z= 0.3 – 1, which means that they are between about 4 and 8 billion light-years away (and thus, the light we see from them is about 4-8 billion years old).

They didn’t just look at the images of the galaxies in question, though; a bias towards classifying those galaxies that show active nuclei to be more distorted from mergers might creep in. Rather, they created a “control group” of galaxies, using images of inactive galaxies from the same redshift as the AGN host galaxies. They took the images from the Cosmic Evolution Survey (COSMOS), a survey of a large region of the sky in multiple wavelengths of light. Since these galaxies were from the same redshift as the ones they wanted to study, they show the same stage in galactic evolution. In all, they had 1264 galaxies in their comparison sample.

The way they designed the study involved a tenet of science that is not normally used in the field of astronomy: the blind study. Cisternas and his team had 9 comparison galaxies – which didn’t contain AGN – of the same redshift for each of their 140 galaxies that showed signs of having an active nucleus.

What they did next was remove any sign of the bright active nucleus in the image. This means that the galaxies in their sample of 140 galaxies with AGN would essentially appear to even a trained eye as a galaxy without the telltale signs of an AGN. They then submitted the control galaxies and the altered AGN images to ten different astronomers, and asked them to classify them all as “distorted”, “moderately distorted”, or “not distorted”.

Since their sample size was pretty manageable, and the distortion in many of the galaxies would be too subtle for a computer to recognize, the pattern-seeking human brain was their image analysis tool of choice. This may sound familiar – something similar is being done with enormous success with people who are amateur galaxy classifiers at Galaxy Zoo.

When a galaxy merges with another galaxy, the merger distorts its shape in ways that are identifiable – it will warp a normally smooth elliptical galaxy out of shape, and if the galaxy is a spiral the arms seem to be a bit “unwound”. If it were the case that galactic mergers are the most likely cause of AGN, then those galaxies with an active nucleus would be more probable to show distortion from this past merger.

The team went through this process of blinding the study to eliminate any bias that those looking at the images would have towards classifying AGN as more distorted. By both having a reasonably large sample size of galaxies and removing any bias when analyzing the images, they hoped to definitively show whether the correlation between AGN and mergers exists.

The result? Those galaxies with an Active Galactic Nucleus did not show any more distortion on the whole than those galaxies in the comparison sample. As the authors state in the paper, “Mergers and interactions involving AGN hosts are not dominant, and occur no more frequently than for inactive galaxies.”

This means that astronomers can’t point towards galactic mergers as the main reason for AGN. The study showed that at least 75% of AGN creation – at least between the last 4-8 billion years – must be from sources other than galactic mergers. Likely candidates for these sources include: “galactic harrassment”, those galaxies that don’t collide, but come close enough to gravitationally influence each other; the instability of the central bar in a galaxy; or the collision of giant molecular clouds within the galaxy.

Knowing that AGN aren’t caused in large part by galactic mergers will help astronomers to better understand the formation and evolution of galaxies. The active nuclei in galaxies that host them greatly influence galactic formation. This process is called ‘AGN feedback’, and the mechanisms and effects that result from the interplay between the energy streaming out of the AGN and the surrounding material in the center of a galaxy is still a hot topic of study in astronomy.

Mergers in the more distant past than 8 billion years might yet correlate with AGN – this study only rules out a certain population of these galaxies – and this is a question that the team plans to take on next, pending surveys by the Hubble Space Telescope and the James Webb Space Telescope. Their study will be published in the January 10 issue of the Astrophysical Journal, and a pre-print version is available on Arxiv.

Source: HST news release, Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, Arxiv paper