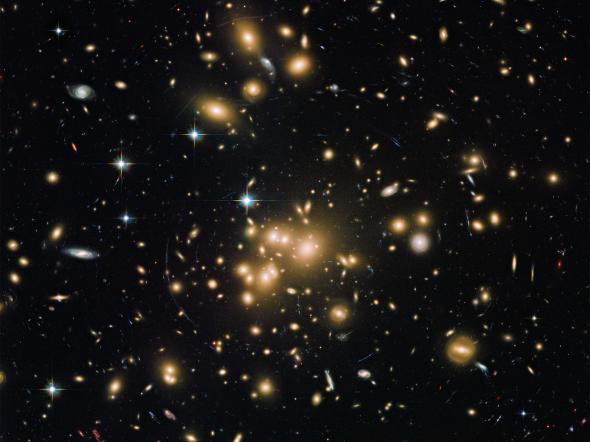

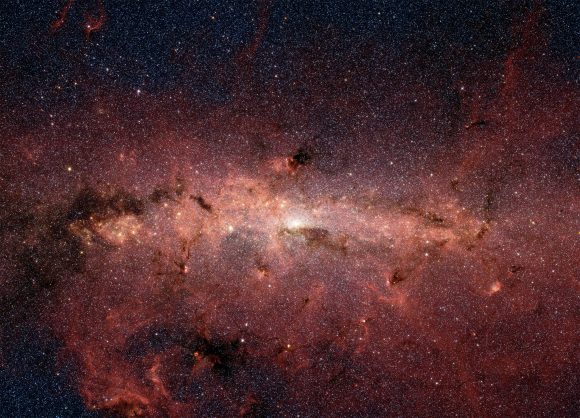

For decades, astrophysicists have puzzled over the relationship between Supermassive Black Holes (SMBHs) and their respective galaxies. Since the 1970s, it has been understood the majority of massive galaxies have an SMBH at their center, and that these are surrounded by rotating tori of gas and dust. The presence of these black holes and tori are what cause massive galaxies to have an Active Galactic Nucleus (AGN).

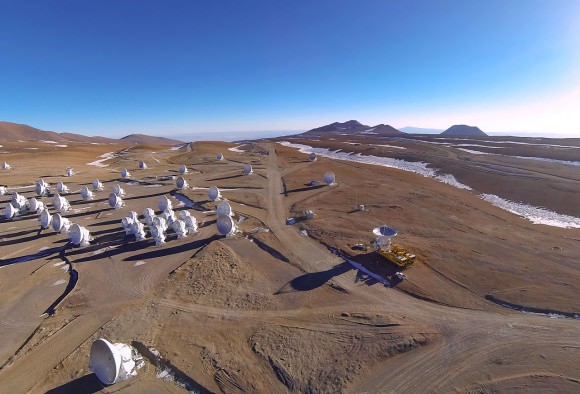

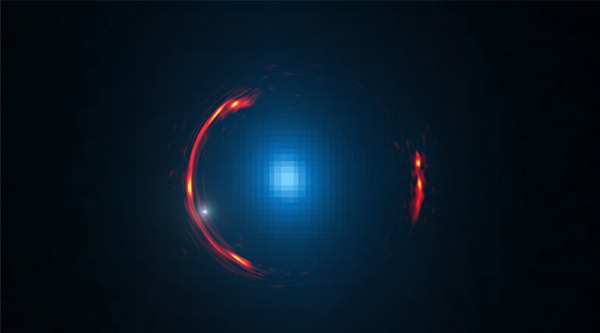

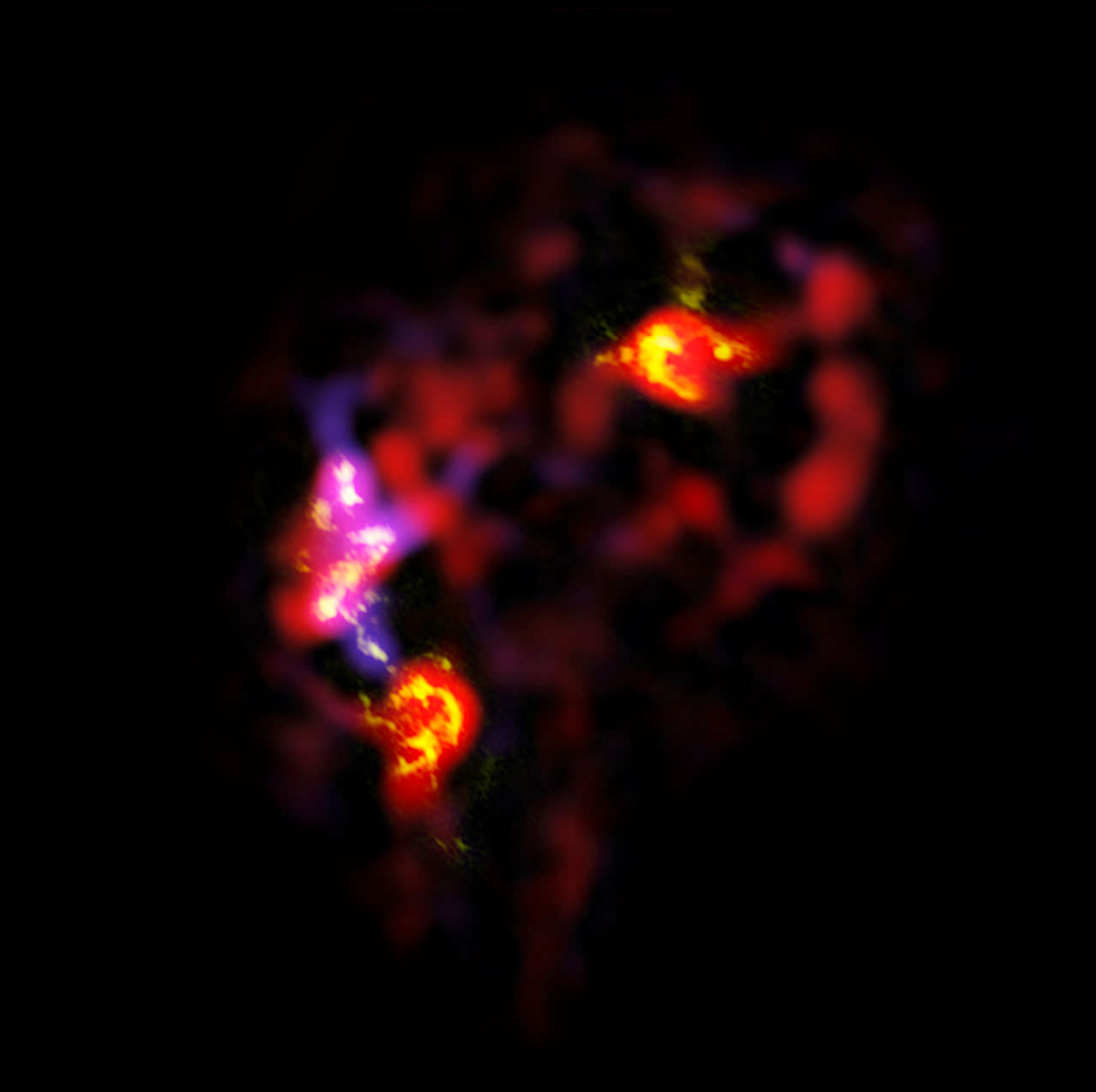

However, a recent study conducted by an international team of researchers revealed a startling conclusion when studying this relationship. Using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) to observe an active galaxy with a strong ionized gas outflow from the galactic center, the team obtained results that could indicate that there is no relationship between a an SMBH and its host galaxy.

The study, titled “No sign of strong molecular gas outflow in an infrared-bright dust-obscured galaxy with strong ionized-gas outflow“, recently appeared in the Astrophysical Journal. The study was led by Yoshiki Toba of the Academia Sinica Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics in Taiwan and included members from Ehime University, Kogakuin University, and the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, The Graduate University for Advanced Studies (SOKENDAI), and Johns Hopkins University.

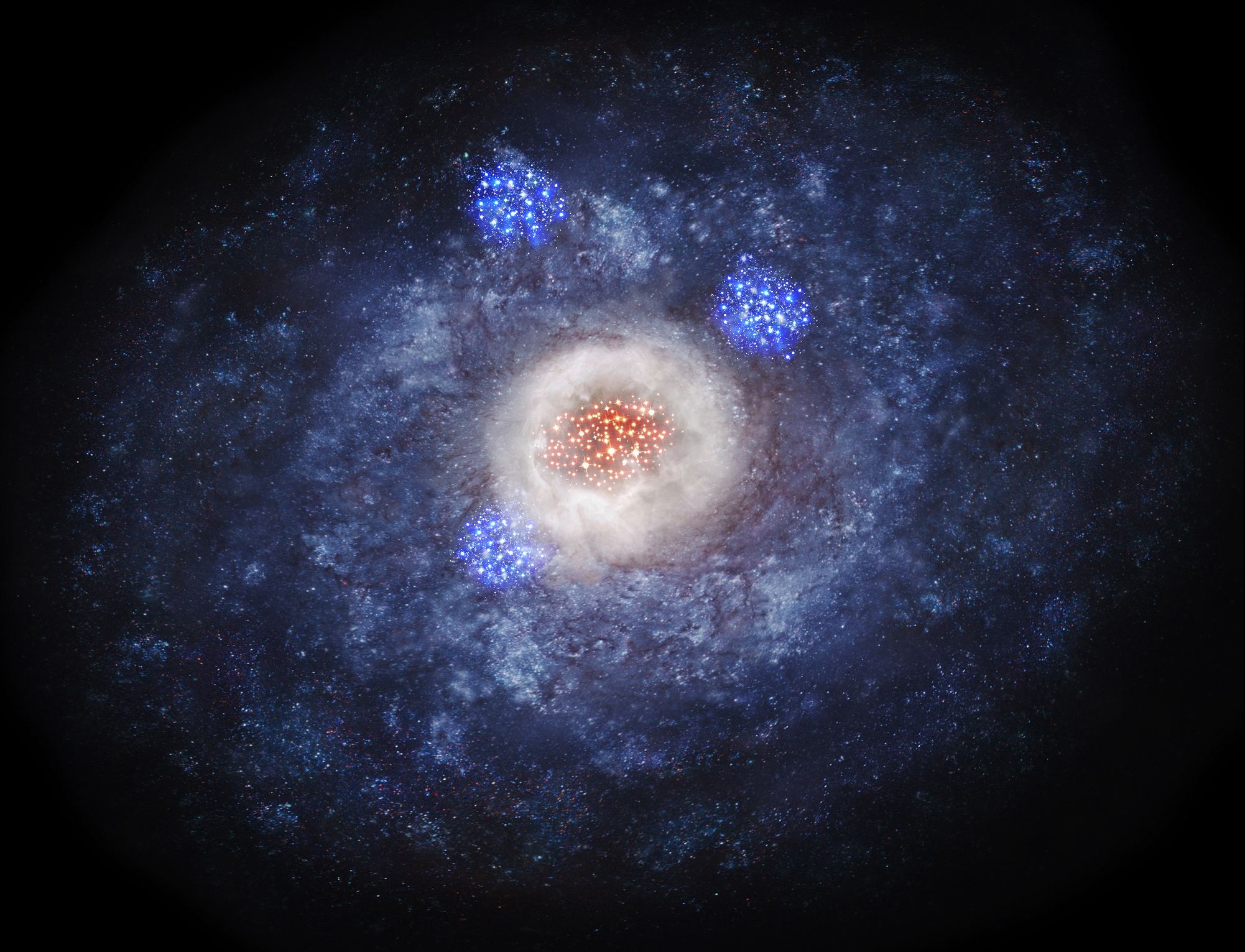

The question of how SMBHs have affected galactic evolution remains one of the greatest unresolved questions in modern astronomy. Among astrophysicists, it is something of a foregone conclusion that SMBHs have a significant impact on the formation and evolution of galaxies. According to this accepted notion, SMBHs significantly influence the molecular gas in galaxies, which has a profound effect on star formation.

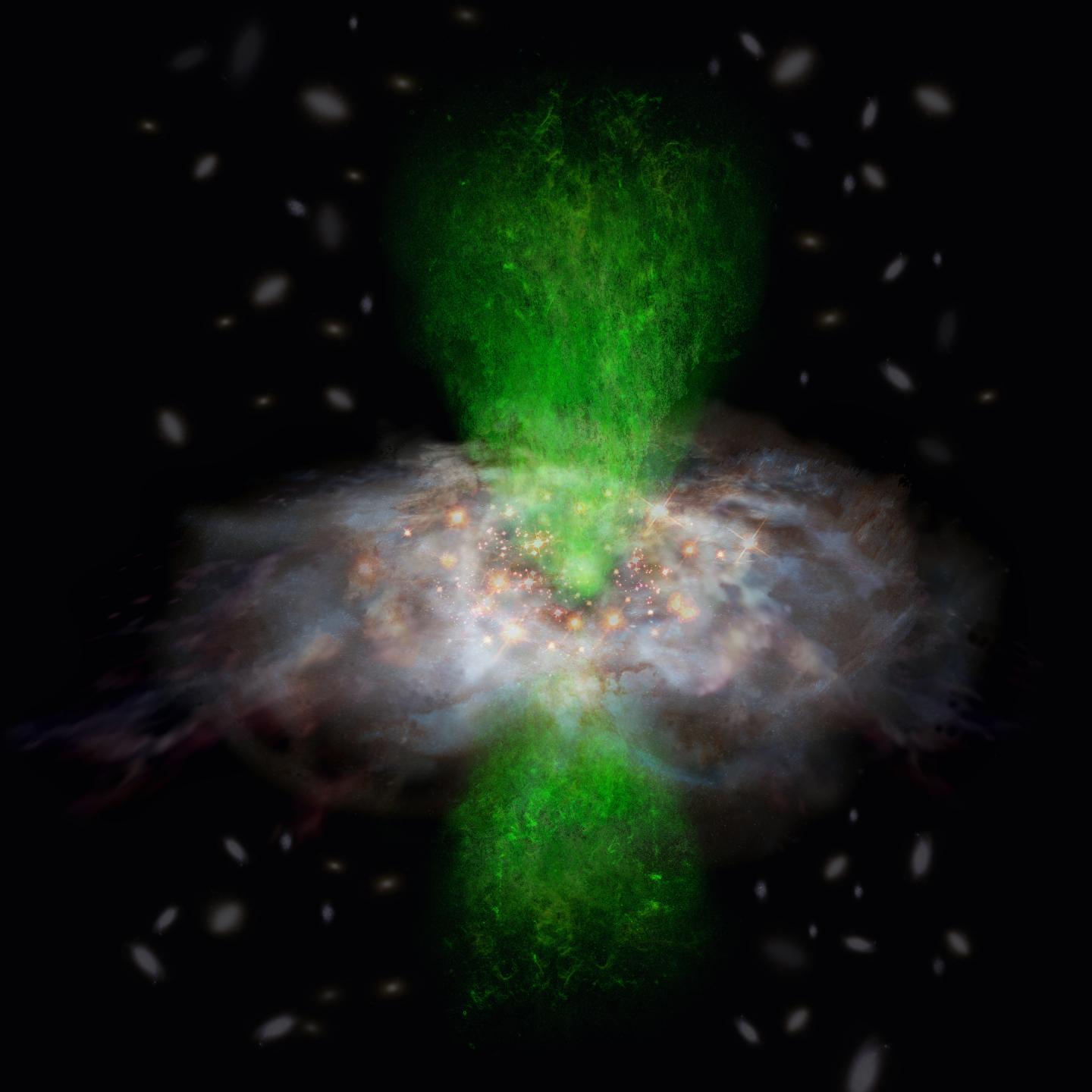

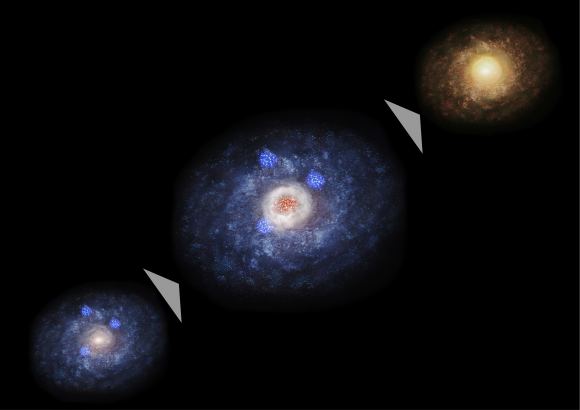

Basically, this theory holds that larger galaxies accumulate more gas, thus resulting in more stars and a more massive central black hole. At the same time, there is a feedback mechanism, where growing black holes accrete more matter on themselves. This results in them sending out a tremendous amount of energy in the form of radiation and particle jets, which is believed to curtail star formation in their vicinity.

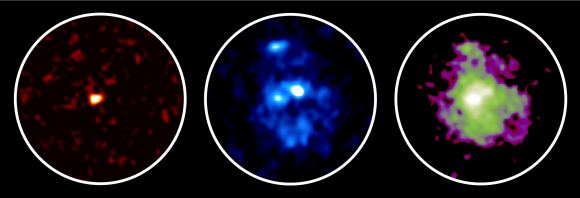

However, when observing an infrared (IR)-bright dust-obscured galaxy (DOG) – WISE1029+0501 – Yoshiki and his colleagues obtained results that contradicted this notion. After conducting a detailed analysis using ALMA, the team found that there were no signs of significant molecular gas outflow coming from WISE1029+0501. They also found that star-forming activity in the galaxy was neither more intense or suppressed.

This indicates that a strong ionized gas outflow coming from the SMBH in WISE1029+0501 did not significantly affect the surrounding molecular gas or star formation. As Dr. Yoshiki Toba explained, this result:

“[H]as made the co-evolution of galaxies and supermassive black holes more puzzling. The next step is looking into more data of this kind of galaxies. That is crucial for understanding the full picture of the formation and evolution of galaxies and supermassive black holes”.

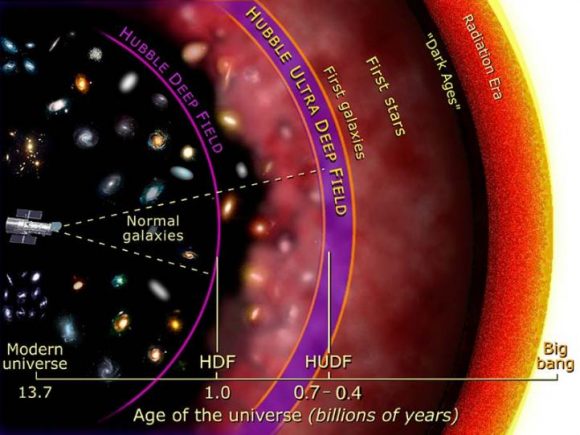

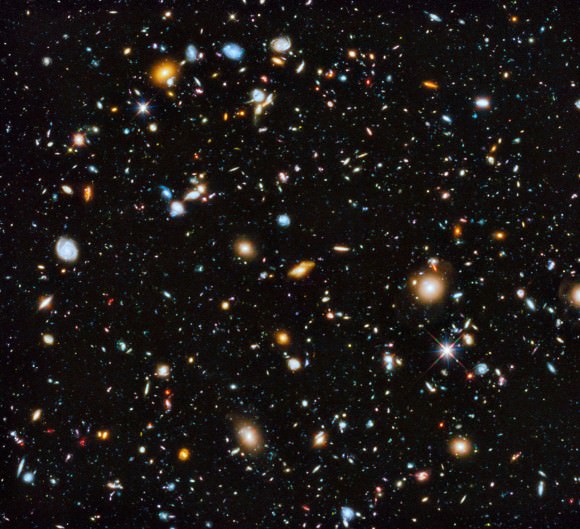

This not only flies in the face of conventional wisdom, but also in the face of recent studies that showed a tight correlation between the mass of central black holes and those of their host galaxies. This correlation suggests that supermassive black holes and their host galaxies evolved together over the course of the past 13.8 billion years and closely interacted as they grew.

In this respect, this latest study has only deepened the mystery of the relationship between SMBHs and their galaxies. As Tohru Nagao, a Professor at Ehime University and a co-author on the study, indicated:

“[W]e astronomers do not understand the real relation between the activity of supermassive black holes and star formation in galaxies. Therefore, many astronomers including us are eager to observe the real scene of the interaction between the nuclear outflow and the star-forming activities, for revealing the mystery of the co-evolution.”

The team selected WISE1029+0501 for their study because astronomers believe that DOGs harbor actively growing SMBHs in their nuclei. In particular, WISE1029+0501 is an extreme example of galaxies where outflowing gas is being ionized by the intense radiation from its SMBH. As such, researchers have been highly motivated to see what happens to this galaxy’s molecular gas.

The study was made possible thanks to ALMA’s sensitivity, which is excellent when it comes to investigating the properties of molecular gas and star-forming activity in galaxies. In fact, multiple studies have been conducted in recent years that have relied on ALMA to investigate the gas properties and SMBHs of distant galaxies.

And while the results of this study contradict widely-held theories about galactic evolution, Yoshiki and his colleagues are excited about what this study could reveal. In the end, it may be that radiation from a SMBH does not always affect the molecular gas and star formation of its host galaxy.

“[U]nderstanding such co-evolution is crucial for astronomy,” said Yoshiki. “By collecting statistical data of this kind of galaxies and continuing in more follow-up observations using ALMA, we hope to reveal the truth.”

Further Reading: ALMA Observatory, Astrophysical Journal