This article is a guest post by Anna Ho, who is currently doing research on stars in the Milky Way through a one-year Fulbright Scholarship at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy (MPIA) in Heidelberg, Germany.

In the Milky Way, an average of seven new stars are born every year. In the distant galaxy GN20, an astonishing average of 1,850 new stars are born every year. “How,” you might ask, indignant on behalf of our galactic home, “does GN20 manage 1,850 new stars in the time it takes the Milky Way to pull off one?”

To answer this, we would ideally take a detailed look at the stellar nurseries in GN20, and a detailed look at the stellar nurseries in the Milky Way, and see what makes the former so much more productive than the latter.

But GN20 is simply too far away for a detailed look.

This galaxy is so distant that its light took twelve billion years to reach our telescopes. For reference, Earth itself is only 4.5 billion years old and the universe itself is thought to be about 14 billion years old. Since light takes time to travel, looking out across space means looking back across time, so GN20 is not only a distant, but also a very ancient, galaxy. And, until recently, astronomers’ vision of these distant, ancient galaxies has been blurry.

Consider what happens when you try to load a video with a slow Internet connection, or when you download a low-resolution picture and then stretch it. The image is pixelated. What was once a person’s face becomes a few squares: a couple of brown squares for hair, a couple of pink squares for the face. The low-definition picture makes it impossible to see details: the eyes, the nose, the facial expression.

A face has many details and a galaxy has many varied stellar nurseries. But poor resolution, a result simply of the fact that ancient galaxies like GN20 are separated from our telescopes by vast cosmic distances, has forced astronomers to blur together all of this rich information into a single point.

The situation is completely different here at home in the Milky Way. Astronomers have been able to peer deep into stellar nurseries and witness stellar birth in stunning detail. In 2006, the Hubble Space Telescope took this unprecedentedly detailed action shot of stellar birth at the heart of the Orion Nebula, one of the Milky Way’s most famous stellar nurseries:

There are over 3,000 stars in this image: The glowing dots are newborn stars that have recently emerged from their cocoons. Stellar cocoons are made of gas: thousands of these gas cocoons sit nestled in immense cosmic nurseries, which are rich with gas and dust. The central region of that Hubble image, encased by what looks like a bubble, is so clear and bright because the massive stars within have blown away the dust and gas they were forged from. Majestic stellar nurseries are scattered all over the Milky Way, and astronomers have been very successful at uncloaking them in order to understand how stars are made.

Observing nurseries both here at home and in relatively nearby galaxies has enabled astronomers to make great leaps in understanding stellar birth in general: and, in particular, what makes one nursery, or one star formation region, “better” at building stars than another. The answer seems to be: how much gas there is in a particular region. More gas, faster rate of star birth. This relationship between the density of gas and the rate of stellar birth is called the Kennicutt-Schmidt Law. In 1959, the Dutch astronomer Maarten Schmidt raised the question of how exactly increasing gas density influences star birth, and forty years later, in an illustration of how scientific dialogues can span decades, his American colleague Robert Kennicutt used data from 97 galaxies to answer him.

Understanding the Kennicutt-Schmidt Law is crucial for determining how stars form and even how galaxies evolve. One fundamental question is whether there is one rule that governs all galaxies, or whether one rule governs our galactic neighborhood, but a different rule governs distant galaxies. In particular, a family of distant galaxies known as “starburst galaxies” seems to contain particularly productive nurseries. Dissecting these distant, highly efficient stellar factories would mean probing galaxies as they used to be, back near the beginning of the universe.

Enter GN20. GN20 is one of the brightest, most productive of these starburst galaxies. Previously a pixelated dot in astronomers’ images, GN20 has become an example of a transformation in technological capability.

In December 2014, an international team of astronomers led by Dr. Jacqueline Hodge of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory in the USA, and comprising astronomers from Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Austria, were able to construct an unprecedentedly detailed picture of the stellar nurseries in GN20. Their results were published earlier this year.

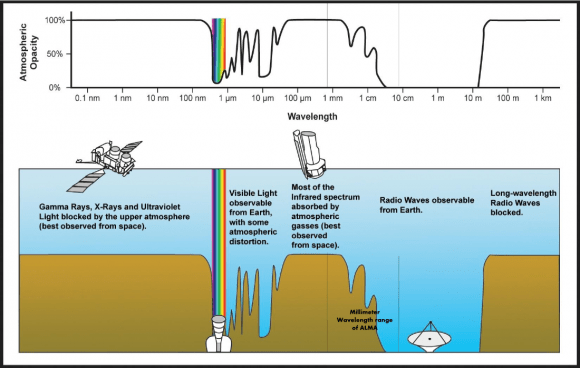

The key is a technique called interferometry: observing one object with many telescopes, and combining the information from all the telescopes to construct one detailed image. Dr. Hodge’s team used some of the most sophisticated interferometers in the world: the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (VLA) in the New Mexico desert, and the Plateau de Bure Interferometer (PdBI) at 2550 meters (8370 feet) above sea level in the French Alps.

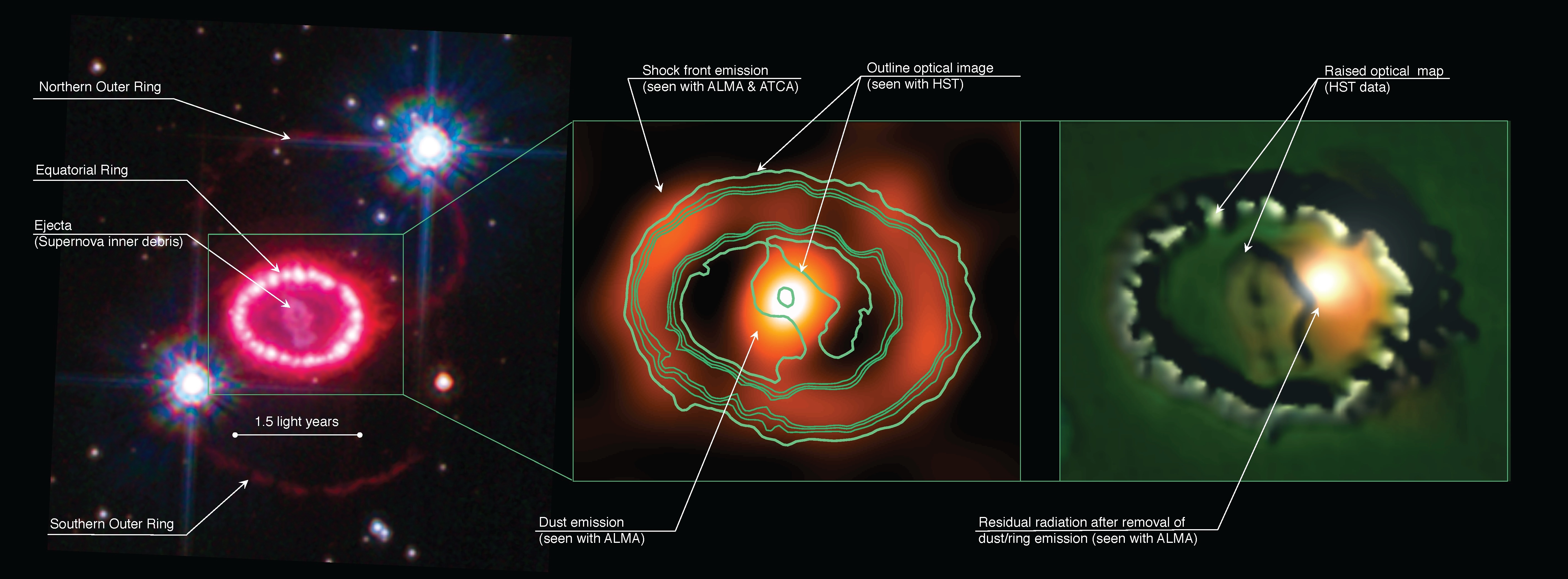

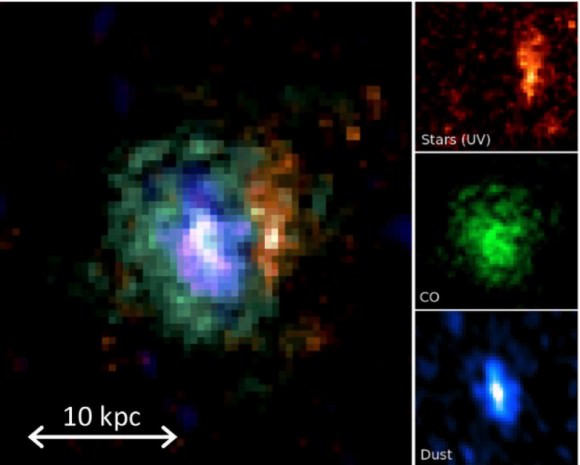

With data from these interferometers as well as the Hubble Space Telescope, they turned what used to be one dot into the following composite image:

This is a false color image, and each color stands for a different component of the galaxy. Blue is ultraviolet light, captured by the Hubble Space Telescope. Green is cold molecular gas, imaged by the VLA. And red is warm dust, heated by the star formation it is shrouding, detected by the PdBI.

Unbundling one pixel into many enabled the team to determine that the nurseries in a starburst galaxy like GN20 are fundamentally different from those in a “normal” galaxy like the Milky Way. Given the same amount of gas, GN20 can churn out orders of magnitude more stars than the Milky Way can. It doesn’t simply have more raw material: it is more efficient at fashioning stars out of it.

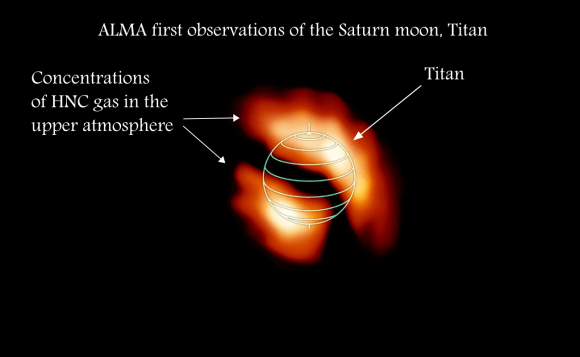

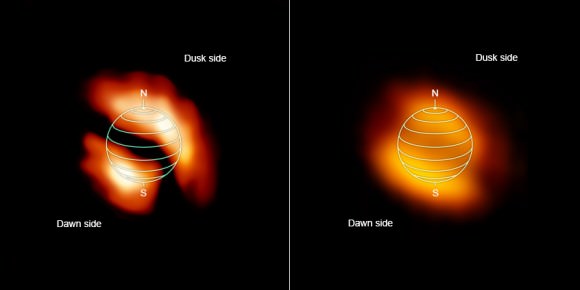

This kind of study is currently unique to the extreme case of GN20. However, it will be more common with the new generation of interferometers, such as the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA).

Located 5000 meters (16000 feet) high up in the Chilean Andes, ALMA is poised to transform astronomers’ understanding of stellar birth. State-of-the-art telescopes are enabling astronomers to do the kind of detailed science with distant galaxies – ancient galaxies from the early universe – that was once thought to be possible only for our local neighborhood. This is crucial in the scientific quest for universal physical laws, as astronomers are able to test their theories beyond our neighborhood, out across space and back through time.