Welcome back to Constellation Friday! Today, in honor of the late and great Tammy Plotner, we will be dealing with the sea monster – the Cetus constellation!

In the 2nd century CE, Greek-Egyptian astronomer Claudius Ptolemaeus (aka. Ptolemy) compiled a list of all the then-known 48 constellations. This treatise, known as the Almagest, would be used by medieval European and Islamic scholars for over a thousand years to come, effectively becoming astrological and astronomical canon until the early Modern Age.

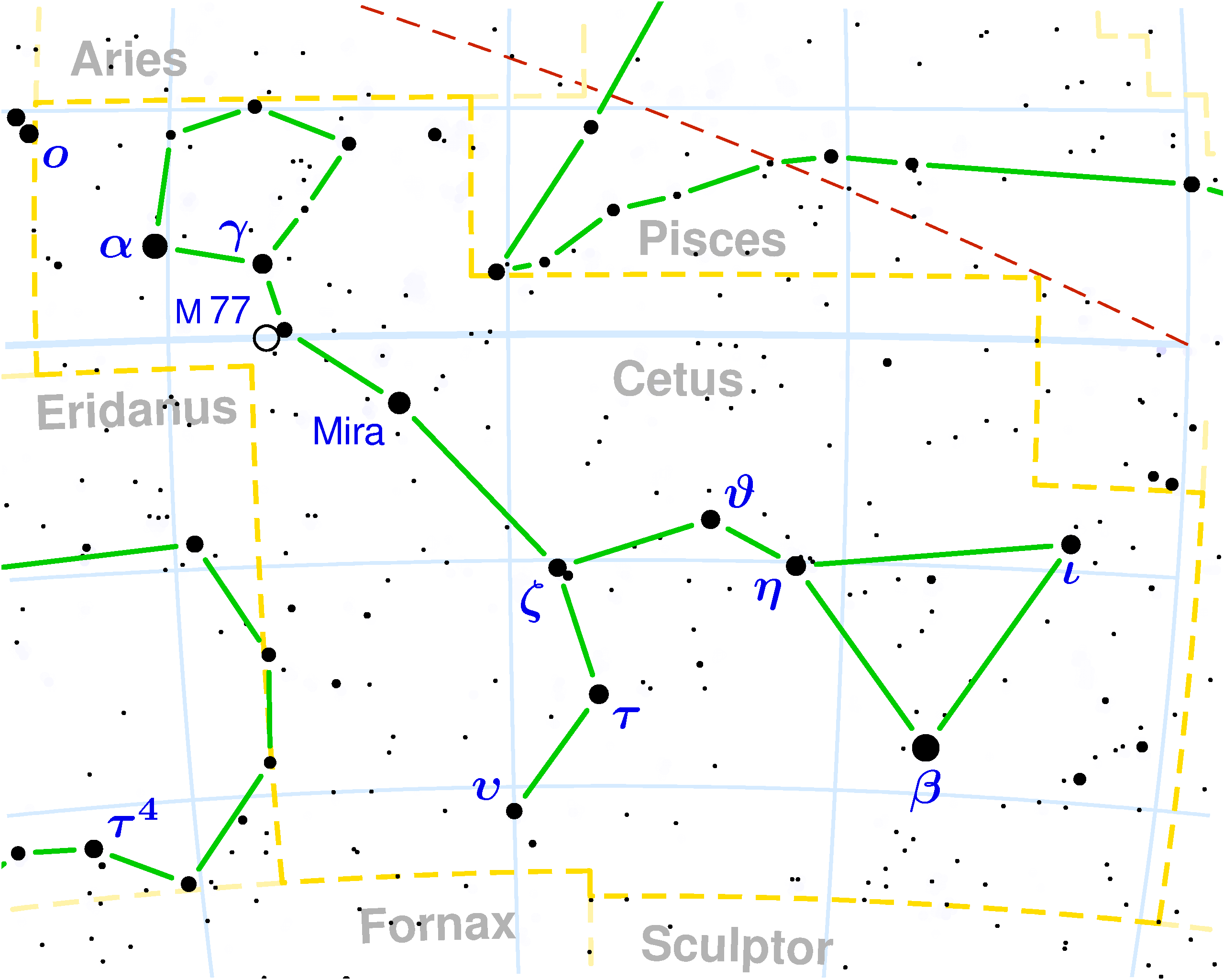

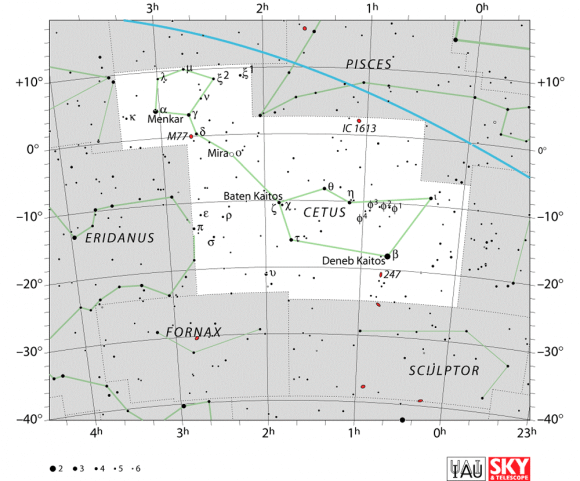

One of these constellations is Cetus, which was named in honor of the sea monster from Greek mythology. Cetus is the fourth largest constellation in the sky, the majority of which resides just below the ecliptic plane. Here, it is bordered by many “watery” constellations – including Aquarius, Pices, Eridanus, Piscis Austrinus, Capricornus – as well as Aries, Sculptor, Fornax and Taurus. Today, it is one of the 88 modern constellations recognized by the IAU.

Name and Meaning:

In mythology, Cetus ties in with the legendary Cepheus,Cassiopeia, Andromeda, Perseus tale – for Cetus is the monster to which poor Andromeda was to be sacrificed. (This whole tale is quite wonderful when studied, for we can also tie in Pegasus as Perseus’ horse, Algol and the whom he slew to get to Andromeda and much, much more!)

As for poor, ugly Cetus. He also represents the gates to the underworld thanks to his position just under the ecliptic plane. Arab legend has it that Cetus carries two pearl necklaces – one broken and the other intact – which oddly enough, you can see among its faint stars in the circular patterns when nights are dark. No matter what the legends are, Cetus is an rather dim, but interesting constellation!

History of Observation:

Cetus was one of many Mesopotamian constellations that passed down to the Greeks. Originally, Cetus may have been associated with a whale, and is often referred to as the Whale. However, its most common representation is that of the sea monster that was slain by Perseus.

In the 17th century, Cetus was depicted variously as a “dragon fish” (by Johann Bayer), and as a whale-like creature by famed 17th-century cartographers Willem Blaeu and Andreas Cellarius. However, Cetus has also been variously depicted with animal heads attached to an aquatic animal body.

The constellation is also represented in many non-Western astrological systems.In Chinese astronomy, the stars of Cetus are found among the Black Tortoise of the North (B?i F?ng Xuán W?) and the White Tiger of the West (X? F?ng Bái H?).

Notable Features:

Cetus sprawls across 1231 square degrees of sky and contains 15 main stars, highlighted by 3 bright stars and 88 Bayer/Flamsteed designations. It’s brightest star is Beta Ceti, otherwise known as Deneb Kaitos (Diphda), a type K0III orange giant which is located approximately 96.3 light years away. This star has left its main sequence and is on its way to becoming a red giant.

The name Deneb Kaitos is derived from the Arabic “Al Dhanab al Kaitos al Janubiyy”, which translates as “the southern tail of Cetus”. The name Diphda comes “ad-dafda at-tani“, which is Arabic for “the second frog” – the star Fomalhaut in neighboring Piscis Austrinus is usually referred to as the first frog.)

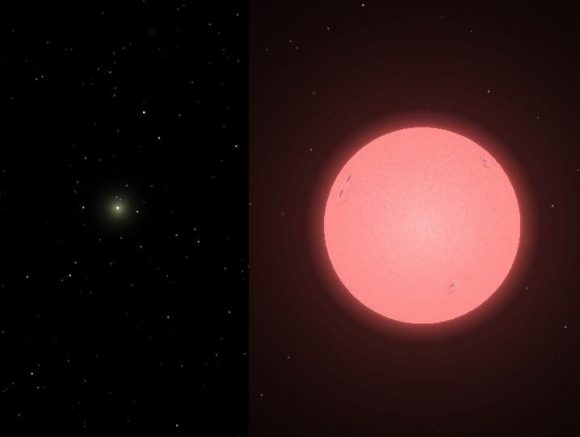

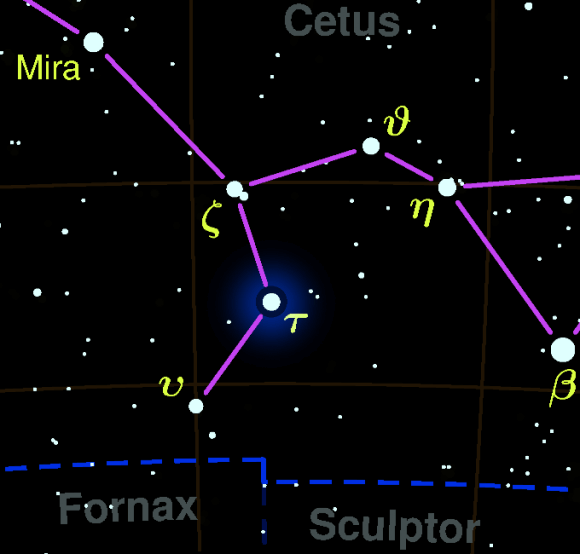

Then there’s Alpha Ceti, a very old red giant star located approximately 249 light years from Earth. It’s traditional name (Menkar), is derived from the Arabic word for “nostril”. Then comes Omicron Ceti, also known as Mira, binary star consisting located approximately 420 light years away. This binary system consists of an oscillating variable red giant (Mira A).

After being recorded for the first time by David Fabricius (on August 3, 1596), Mira has since gone on to become the prototype for the Mira class of variables (of which there are six or seven thousand known examples). These stars are red giants whose surfaces oscillate in such a way as to cause variations in brightness over periods ranging from 80 to more than 1,000 days.

Cetus is also home to many Deep Sky Objects. A notable examples is the barred spiral galaxy known as Messier 77, which is located approximately 47 million light years away and is 170,000 light years in diameter, making it one of the largest galaxies listed in Messier’s catalogue. It has an Active Galactic Nucleus (AGN) which is obscured from view by intergalactic dust, but remains an active radio source.

Then there’s NGC 1055, a spiral galaxy that lies just 0.5 north by northeast of Messier 77. It is located approximately 52 million light years away and is seen edge-on from Earth. Next to Messier 77, NGC 1055 is a largest member of a galaxy group – measuring 115,800 light years in diameter – that also includes NGC 1073 and several smaller irregular galaxies. It has a diameter of about 115,800 light years. The galaxy is a known radio source.

Finding Cetus:

Cetus is the fourth largest constellation in the sky, is visible at latitudes between +70° and -90° and is best seen at culmination during the month of November. Of all the stars in Cetus, the very first you must look for in binoculars is Mira. Omicron Ceti was the very first variable star discovered and was perhaps known as far back as ancient China, Babylon or Greece. The variability was first recorded by the astronomer David Fabricius while observing Mercury.

Now aim your binoculars at Alpha Ceti. It’s name is Menkar and we do know something about it. Menkar is an old and dying star, long past the hydrogen and perhaps even past the helium stage of its stellar evolution. Right now it’s a red giant star but as it begins to burn its carbon core it will likely become highly unstable before finally shedding its outer layers and forming a planetary nebula, leaving a relatively large white dwarf remnant.

Hop down to Beta Ceti – Diphda. Oddly enough, Diphda is actually the brightest star in Cetus, despite its beta designation. It is a giant star with a stellar corona that’s brightening with age – exerting about 2000 times more x-ray power than our Sun! For some reason, it has gone into an advanced stage if stellar evolution called core helium burning – where it is converting helium directly to carbon.

Are you ready to get out your telescope now? Then aim at Diphda and drop south a couple of degrees for NGC 247. This is a very definite spiral galaxy with an intense “stellar” nucleus! Sitting right up in the eyepiece as a delightful oval, the NGC 247 is has a very proper galaxy structure with a defined core area and a concentration that slowly disperses toward its boundaries with one well-defined dark dust lane helping to enhance a spiral arm. Most entertaining! Continuing “down” we move on to the NGC 253. Talk about bright!

Very few galactic studies come in this magnitude (small telescopes will pick it up very well, but it requires large aperture to study structure.) Very elongated and hazy, it reminds me sharply of the “Andromeda Galaxy”. The center is very concentrated and the spiral arms wrap their way around it beautifully! Dust lanes and bright hints of concentration are most evident. and its most endearing feature is that it seems to be set within a mini “Trapezium” of stars. A very worthy study…

Now, let’s hop off to Delta Ceti, shall we? I want to rock your world – because spiral galaxy M77 rocked mine! Once again, easily achieved in the small telescope, Messier 77 comes “alive” with aperture. This one has an incredible nucleus and very pronounced spiral arms – three big, fat ones! Underscored by dark dust lanes, the arms swirl away from the center in a galactic display that takes your breath away!

The “mottling” inside the structure is not just a hint in this ovalish galaxy. I guarantee you won’t find this one “ho hum”… how could you when you know you’re looking at something that’s 47.0 million light-years away! Messier 77 is an active galaxy with an Active Galactic Nucleus (AGN) and one of the brightest Seyfert galaxies known.

Now, return to Delta and the “fall line” runs west to east on the north side. First up is galaxy NGC 1073, a very pretty little spiral galaxy with a very “stretched” appearing nucleus that seems to be “ringed” by its arms! Continuing along the same trajectory, we find the NGC 1055. Oh, yes… Edge-on, lenticular galaxy! This soft streak of light is accompanied by a trio of stars. The galaxy itself is cut through by a dark dust lane, but what appears so unusual is the core is to one side!

Now we’ve made it to back to the incredible M77, but let’s keep on the path and pick up the NGC 1087 – a nice, even-looking spiral galaxy with a bright nucleus and one curved arm. Ready to head for the beautiful variable Mira again? Then let her be the guide star, because halfway between there and Delta is the NGC 936 – a soft spiral galaxy with a “saturn” shaped nucleus. Nice starhoppin’!

We have written many interesting articles about the constellation here at Universe Today. Here is What Are The Constellations?, What Is The Zodiac?, and Zodiac Signs And Their Dates.

Be sure to check out The Messier Catalog while you’re at it!

For more information, check out the IAUs list of Constellations, and the Students for the Exploration and Development of Space page on Canes Venatici and Constellation Families.

Sources: