The hazy, white horizon lifts away slowly, giving way to the blue and green, cloud-swept marble we call home. I take in a deep breath, astonished by the Earth’s staggering beauty in stark contrast to the sprinkled backdrop.

People are still shuffling into the 429-seat Hayden Planetarium at the American Museum of Natural History, their shadows projected onto the arched ceiling. A voice resonates in the dome’s spacious cavity. Brian Abbott, the planetarium’s assistant director, is welcoming everyone to the show. It’s a “highlights tour,” he says, covering most of the known universe in one fell swoop.

As we leave Earth further behind, the satellites appear, swarming above our planet like bees around a hive. Soon the curved orbits of other planets become visible and we fly toward Mars.

In minutes we are hovering above Valles Marineris, a canyon so massive it would stretch from Manhattan to Los Angeles. The projectors display six-meter resolution data from the Mars Global Surveyor. We see the canyon ridges in such incredible, 3D detail it seems we could reach out and touch the tallest peaks with our fingers.

Abbott’s voice is slow and soothing. He speaks with authority, mindful of every inflection he makes and every word he uses. He carefully constructs his sentences, but also takes the time to crack a few jokes along the way. It’s just another day at the office, and yet it sounds like he’s having the time of his life.

Abbott never dreamed of becoming an astronomer. In high school he was on a very different path, headed toward a career in art. Then, in 1985, Halley’s comet was scheduled to appear in the night sky. “For some reason I needed to find it,” he said. So, from his backyard outside Philadelphia, he learned how to pinpoint the constellations and spot distant objects, like galaxies, nebulae and star clusters. When the comet finally came, he was able to spot it, a tiny target in the vast sky. It was a revelation that pumped him full of adrenalin on that long, dark night.

Yet while Abbott left art as a career choice behind, he has been able to integrate art with astronomy, as his planetarium show demonstrates. “I admire the niche he has created for himself in the intersection between art, visualization and science,” said colleague Jana Grcevich, a postdoctoral researcher at AMNH.

Just before starting work at the museum in 1999, however, Abbott was an unhappy graduate student in the astronomy department at the University of Toledo. “Who can explain what gets you out of bed in the morning,” he said. “It just wasn’t what moved me.” Frustrated with his lot in life, he had plans to drive his car across the country, Jack Kerouac style. But first, he attended one last meeting: the American Astronomical Society’s annual conference in Chicago.

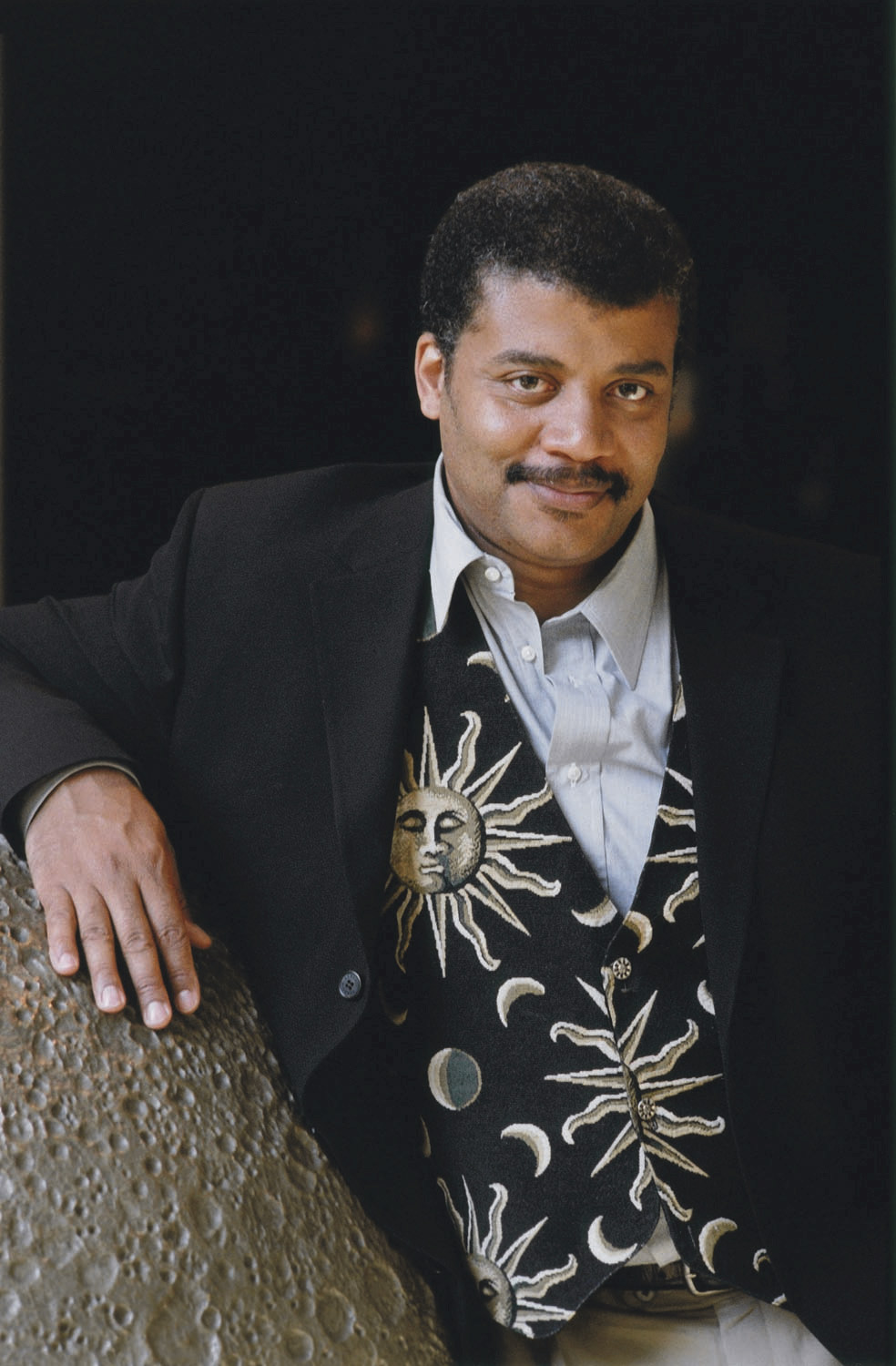

There, among all the job listings, he saw only one that wasn’t a research or a faculty position. The AMNH needed someone to create the world’s first interactive atlas of the Universe. So Abbott started sniffing around and coincidentally ran into the planetarium’s famed director, Neil DeGrasse Tyson, in the hallway of their hotel. Yet “Neil wasn’t Neil back then,” Abbott recalled. “He was somewhat known but he wasn’t mobbed with people.”

The duo started talking, and in two weeks Abbott found himself living in New York City with a new job. But he doesn’t regret it for a second. “I feel like I’m almost divorced from the night sky living here. I’m not able to just go out in my backyard and set up a telescope and see stuff. But we have this great dome. And I can go in there and see the entire Universe far better than I can see in the night sky.”

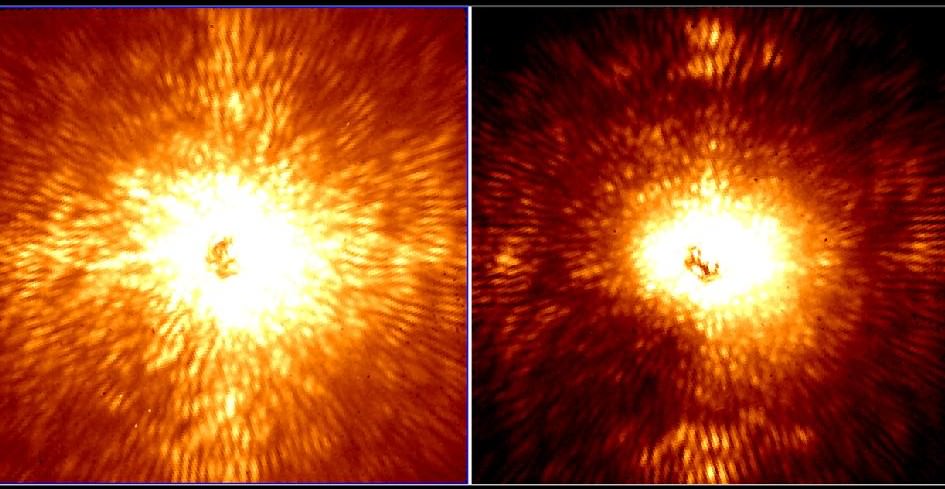

Now, Abbott spends his days visualizing large data sets. For the past 14 years, he has been creating a three-dimensional map of the Universe. He’s constantly updating the atlas with recent data hot off the world’s biggest telescopes and best satellites. And in the planetarium, he turns this abstract data into the planets, stars and galaxies that visitors flock to see. “What we want to do is focus on the scientific story of the universe,” said Abbott. “And we want that reflected in our dome.”

As the Hayden Planetarium’s popularity suggests, there’s a surprising public appetite for such strict scientific cartography. “There’s always at least one time in the show when the air comes out of the room,” said Abbott, referring to the moment when the audience takes a collective breath, in awe of the universe above them.

I can recall easily when that moment came for me. We had just left the Milky Way galaxy. Looking back on our home galaxy, the bright yellow core was surrounded by gorgeous blue spiral arms and sweeping dust lanes. Swarms of smaller galaxies began to appear. In minutes, we saw the Tully Catalogue, which covers an astonishing 30,000 galaxies in total.

The audience gasped in awe at the sheer number of galaxies in our local neighborhood. It’s impossible not to feel small at a moment like that.

But we were nowhere near the farthest reaches of the Universe yet. In moments, we saw the total number of galaxies ever recorded in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. A chill ran down my spine. There were over one million galaxies projected onto the dome. Each one has over 100 billion stars. And each one of those likely has 5 or even ten planets. There are so many opportunities for life in our vast Universe.

We continued to zoom out, until we reached the edges of the 46.6 billion-light-year-wide observable Universe. In just over an hour, the tour had grossly violated the speed of light. “So that’s the Universe,” Abbott said. “Any questions?”