Did you know that it’s been almost 45 years since humans walked on the surface of the Moon? Of course you do. Anyone who loves space exploration obsesses about the last Apollo landings, and counts the passing years of sadness.

Sure, SpaceX, Blue Origins and the new NASA Space Launch Systems rocket offer a tantalizing future in space. But 45 years. Ouch, so much lost time.

What would happen if we could go back in time? What amazing and insane plans did NASA have to continue exploring the Solar System? What alternative future could we have now, 45 years later?

In order to answer this question, I’ve teamed up with my space historian friend, Amy Shira Teitel, who runs the Vintage Space blog and YouTube Channel. We’ve decided to look at two groups of missions that never happened.

In her part, Amy talks about the Apollo Applications Program; NASA’s original plans before the human exploration of the Moon was shut down. More Apollo missions, the beginnings of a lunar base, and even a human flyby of Venus.

In my half of the series, I look at Werner Von Braun’s insanely ambitious plans to send a human mission to Mars. Put it together with Amy’s episode and you can imagine a space exploration future with all the ambition of the Kerbal Space Program.

Keep mind here that we’re not going to constrain ourselves with the pesky laws of physics, and the reality of finances. These ideas were cool, and considered by NASA engineers, but they weren’t necessarily the best ideas, or even feasible.

So, 2 parts, tackle them in any order you like. My part begins right now.

Werner Von Braun, of course, was the architect for NASA’s human spaceflight efforts during the space race. It was under Von Braun’s guidance that NASA developed the various flight hardware for the Mercury, Gemini and Apollo missions including the massive Saturn V rocket, which eventually put a human crew of astronauts on the Moon and safely returned them back to Earth.

Von Braun was originally a German rocket scientist, pivotal to the Nazi “rocket team”, which developed the ballistic V-2 rockets. These unmanned rockets could carry a 1-tonne payload 800 kilometers away. They were developed in 1942, and by 1944 they were being used in war against Allied targets.

By the end of the war, Von Braun coordinated his surrender to the Allies as well as 500 of his engineers, including their equipment and plans for future rockets. In “Operation Paperclip”, the German scientists were captured and transferred to the White Sands Proving Ground in New Mexico, where they would begin working on the US rocket efforts.

Before the work really took off, though, Von Braun had a couple of years of relative downtime, and in 1947 and 1948, he wrote a science fiction novel about the human exploration of Mars.

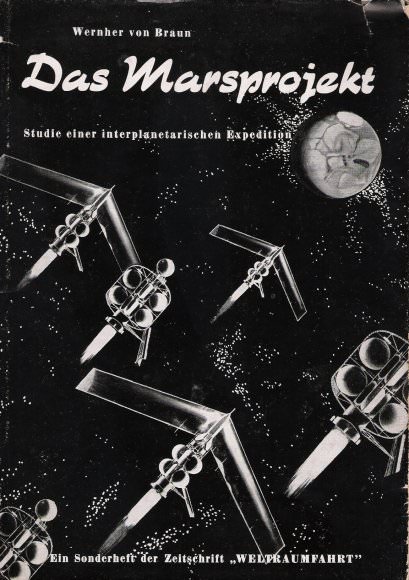

The novel itself was never published, because it was terrible, but it also contained a detailed appendix containing all the calculations, mission parameters, hardware designs to carry out this mission to Mars.

In 1952, this appendix was published in Germany as “Das Marsproject”, or “The Mars Project”. And an English version was published a few years later. Collier’s Weekly Magazine did an 8-part special on the Mars Project in 1952, captivating the world’s imagination.

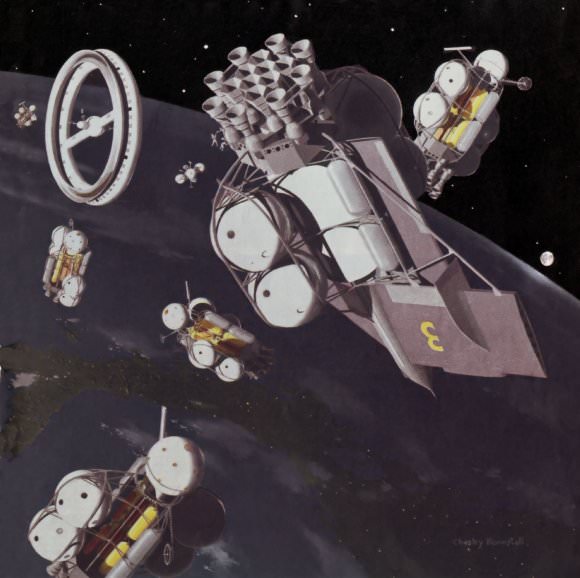

Here’s the plan: In the Mars Project, Von Braun envisioned a vast armada of spaceships that would make the journey from Earth to Mars. They would send a total of 10 giant spaceships, each of which would weigh about 4,000 tonnes.

Just for comparison, a fully loaded Saturn V rocket could carry about 140 tonnes of payload into Low Earth Orbit. In other words, they’d need a LOT of rockets. Von Braun estimated that 950 three-stage rockets should be enough to get everything into orbit.

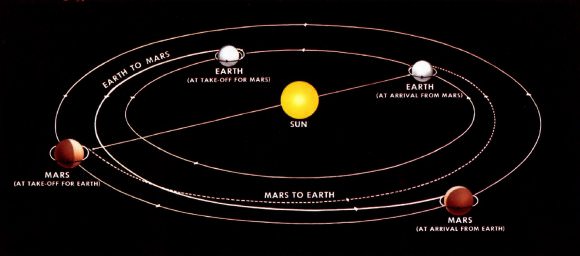

All the ships would be assembled in orbit, and 70 crewmembers would take to their stations for an epic journey. They’d blast their rockets and carry out a Mars Hohmann transfer, which would take them 8 months to make the journey from Earth to Mars.

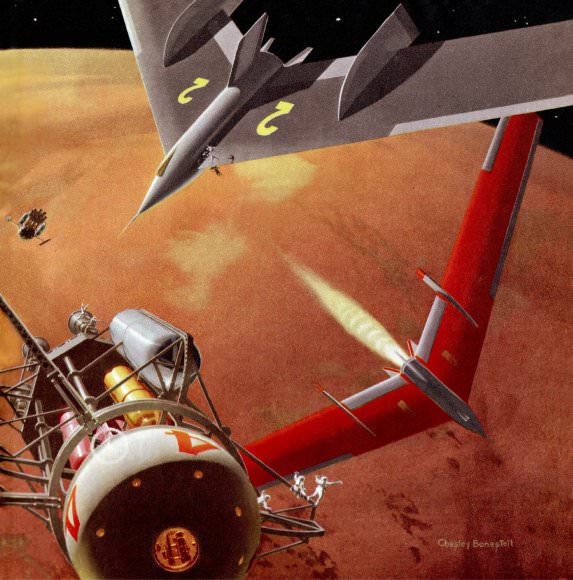

The flotilla consisted of 7 orbiters, huge spheres that would travel to Mars, go into orbit and then return back to Earth. It also consisted of 3 glider landers, which would enter the Martian atmosphere and stay on Mars.

Once they reached the Red Planet, they would use powerful telescopes to scan the Martian landscape and search for safe and scientifically interesting landing spots. The first landing would happen at one of the planet’s polar caps, which Von Braun figured was the only guaranteed flat surface for a landing.

At this point, it’s important to note that Von Braun assumed that the Martian atmosphere was about as thick as Earth’s. He figured you could use huge winged gliders to aerobrake into the atmosphere and land safely on the surface.

He was wrong. The atmosphere on Mars is actually only 1% as thick as Earth’s, and these gliders would never work. Newer missions, like SpaceX’s Red Dragon and Interplanetary Transport Ship will use rockets to make a powered landing.

I think if Von Braun knew this, he could have modified his plans to still make the whole thing work.

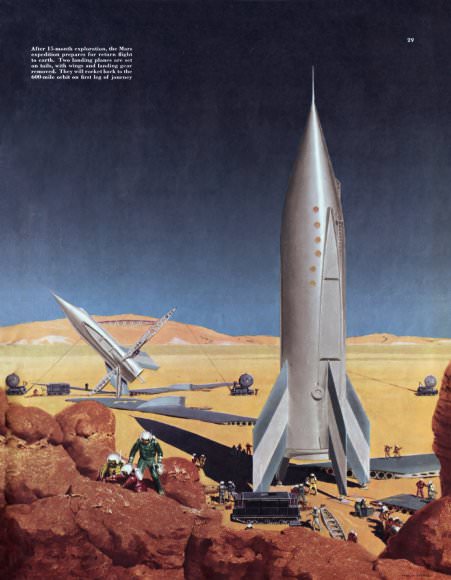

Once the first expedition landed at one of the polar caps, they’d make a 6,400 kilometer journey across the harsh Martian landscape to the first base camp location, and build a landing strip. Then two more gliders would detach from the flotilla and bring the majority of the explorers to the base camp. A skeleton crew would remain in orbit.

Once again, I think it’s important to note that Von Braun didn’t truly understand how awful the surface of Mars really is. The almost non-existent atmosphere and extreme cold would require much more sophisticated gear than he had planned for. But still, you’ve got to admire his ambition.

With the Mars explorer team on the ground, their first task was to turn their glider-landers into rockets again. They would stand them up and get them prepped to blast off from the surface of Mars when their mission was over.

The Martian explorers would set up an inflatable habitat, and then spend the next 400 days surveying the area. Geologists would investigate the landscape, studying the composition of the rocks. Botanists would study the hardy Martian plant life, and seeing what kinds of Earth plants would grow.

Zoologists would study the local animals, and help figure out what was dangerous and what was safe to eat. Archeologists would search the region for evidence of ancient Martian civilizations, and study the vast canal network seen from Earth by astronomers. Perhaps they’d even meet the hardy Martians that built those canals, struggling to survive to this day.

Once again, in the 1940s, we thought Mars would be like the Earth, just more of a desert. There’d be plants and animals, and maybe even people adapted to the hardy environment. With our modern knowledge, this sounds quaint today. The most brutal desert on Earth is a paradise compared to the nicest place on Mars. Von Braun did the best he could with the best science of the time.

Finally, at the end of their 400 days on Mars, the astronauts would blast off from the surface of Mars, meet up with the orbiting crew, and the entire flotilla would make the return journey to Earth using the minimum-fuel Mars-Earth transfer trajectory.

Although Von Braun got a lot of things wrong about his Martian mission plan, such as the thickness of the atmosphere and habitability of Mars, he got a lot of things right.

He anticipated a mission plan that required the least amount of fuel, by assembling pieces in orbit, using the Hohmann transfer trajectory, exploring Mars for 400 days to match up Earth and Mars orbits. He developed the concept of using orbiters, detachable landing craft and ascent vehicles, used by the Apollo Moon missions.

The missions never happened, obviously, but Von Braun’s ideas served as the backbone for all future human Mars mission plans.

I’d like to give a massive thanks to the space historian David S.F. Portree. He wrote an amazing book called Humans to Mars, which details 50 years of NASA plans to send humans to the Red Planet, including a fantastic synopsis of the Mars Project.

I asked David about how Von Braun’s ideas influenced human spaceflight, he said it was his…

“… reliance on a conjunction-class long-stay mission lasting 400 days. That was gutsy – in the 1960s, NASA and contractor planners generally stuck with opposition-class short-stay missions. In recent years we’ve seen more emphasis on the conjunction-class mission mode, sometimes with a relatively short period on Mars but lots of time in orbit, other times with almost the whole mission spent on the surface.”