Note: To celebrate the 40th anniversary of the Apollo 13 mission, for the next 13 days, Universe Today will feature “13 Things That Saved Apollo 13,” discussing different turning points of the mission with NASA engineer Jerry Woodfill. Click here for our preview article.

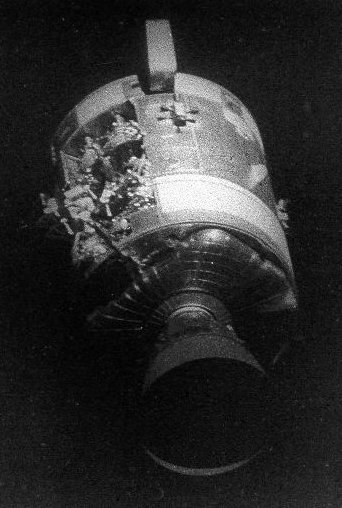

Oxygen Tank two in the Apollo 13 Service Module exploded at Mission Elapsed Time (MET) 55 hours and 55 minutes, 321,860 kilometers (199,990 miles) away from Earth. If the tank was going to rupture and the crew was going to survive the ordeal, the explosion couldn’t have happened at a better time. “Not everyone agrees with all the things I’ve come up with in my research,” said NASA engineer Jerry Woodfill who has studied the Apollo 13 mission in intricate detail, “but pretty much everyone agrees on this, including Jim Lovell. The timing of when the explosion happened was key. Much earlier or later in the mission would have prevented a successful rescue.”

If the explosion happened earlier (and assuming it would have occurred after Apollo 13 left Earth orbit), the distance and time to get back to Earth would have been so great that there wouldn’t have been sufficient power, water and oxygen for the crew to survive. Had it happened much later, perhaps after astronauts Jim Lovell and Fred Haise had already descended to the lunar surface, there would not have been the opportunity to use the lunar lander as a lifeboat.

But looking at why the explosion happened when it did shows how fortuitous the timing ended up to be.

The explosion occurred when Jack Swigert flipped a switch to conduct a “stir” of the O2 tank. The Teflon insulation on the wires to the stirrer motor in O2 tank 2 had unknowingly been damaged because the manufacturer failed to update the heater design for 65 volt operation, and the tank overheated during a pre-flight test, melting the insulation. The damaged wires shorted out and the insulation ignited. The resulting fire rapidly increased pressure beyond its nominal 1,000 psi (7 MPa) limit and either the tank or the tank dome failed.

The O2 tanks were stirred in order to get an accurate reading on the gauging systems, as the cryogenic oxygen tends to solidify in the tanks, and stirring allows for a more accurate reading on the quantity of O2 remaining in the tank.

But this was not the first time the crew had been ordered to stir the tank. It was the fifth time during the mission. And most interestingly, the tanks normally were stirred approximately once every 24 hours. So, why was it stirred that often?

In what Woodfill said was a problem unrelated to what caused the explosion, the quantity sensor or gauge was not working correctly on O2 tank 2. The EECOM (Electrical Environmental and Consumables) flight controller in Houston discovered that the quantity sensor was not reading accurately, and because of that Mission Control asked the astronauts to perform additional actuations of the stirrer to try and troubleshoot why the sensor wasn’t working correctly.

So, it took five actuations until the short circuit and the resulting fire and explosion occurred. If the gauge had been working correctly and the normal stirring of the tank had been done, that would have put the time of the fifth stirring after Lovell and Haise had departed for the lunar surface, and the rescue scenario that ultimately was carried out couldn’t have happened.

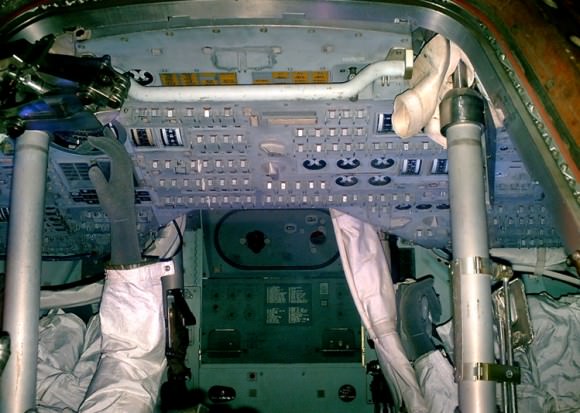

“Check the arithmetic,” said Woodfill. “Five actuations at 24 hour periods amounts to a MET of 120 hours. The lunar lander would have departed for the Moon at 103.5 hours into the mission. At 120 hours into the mission, the crew of Lovell and Haise would have been awakened from their sleep period, having completed their first moon walk eight hours before. They would receive an urgent call from Jack Swigert and/or Mission Control that something was amiss with the mother ship orbiting the Moon.”

Who knows what would have happened to the crew? The fuel cells required the liquid oxygen tanks. This meant no production of electrical power, water and oxygen. The attached lunar lander had to be available. Likely, the two ships couldn’t even have docked back together. And what if the accident had happened behind the Moon without mission control’s help? Alone in the Command module, Swigert would have had difficulty analyzing the problem. Without a fueled lunar lander descent stage attached, lacking its consumables and engines as well as the needed battery power, water and oxygen, the crippled Command Module could not have returned to Earth with live astronaut(s). Not only would Lovell and Haise have perished but Swigert’s fate would have been the same. Even if the damaged Service Module’s engine had worked, no fuel cells meant the ship would die. The situation that the Apollo 13 crew actually faced was dire, but the alternative scenario would certainly have been fatal.

Woodfill contends that the quantity sensor malfunction assured the lunar lander would be present and fully fueled at the time of the disaster. It was an extremely fortuitous event. Had it not occurred, the timing of the explosion would have been far different and the crew would have perished.

Additional Articles from the “13 Things That Saved Apollo 13” series that have now been posted:

Part 2: The Hatch That Wouldn’t Close

Part 3: Charlie Duke’s Measles

Part 4: Using the LM for Propulsion

Part 5: Unexplained Shutdown of the Saturn V Center Engine

Part 6: Navigating by Earth’s Terminator

Part 8: The Command Module Wasn’t Severed

Part 12: Lunar Orbit Rendezvous

Part 13: The Mission Operations Team

Also:

Your Questions about Apollo 13 Answered by Jerry Woodfill (Part 1)

More Reader Questions about Apollo 13 Answered by Jerry Woodfill (part 2)

Final Round of Apollo 13 Questions Answered by Jerry Woodfill (part 3)

Never Before Published Images of Apollo 13’s Recovery

Listen to an interview of Jerry Woodfill on the 365 Days of Astronomy podcast.