NASA’s Curiosity Rover spends most of its time staring at the ground, but like humans, it looks up once in a while too. As reported earlier, NASA ground controllers pointed the rover’s Mast Camera (mastcam) skyward to shoot a series of photos of Comet Siding Spring when it passed closest to the Red Planet on October 19th. Until recently, noise-speckled pictures available on the raw image site confounded interpretation. Was the comet there or wasn’t it? In these recently released versions, the fuzzy intruder is plain to see, tracking from right to left across the field of view.

Ten exposures of 25 seconds each were taken between 4:33 p.m. and 5:54 p.m. CDT on October 19th to create the animation. The few specks you see are electronic noise, but the sharp, bright streaks are stars that trailed during the time exposure. Curiosity’s Mastcam camera system has dual lenses – a 100mm f/10 lens with a 5.1° square field of view and a 34mm, f/8 lens with a 15° square field of view. NASA didn’t include the information about which camera was used to make the photos, but if I had to guess, the faster, wide-angle view would be my choice. Siding Spring was moving relatively quickly across the Martian sky at closest approach.

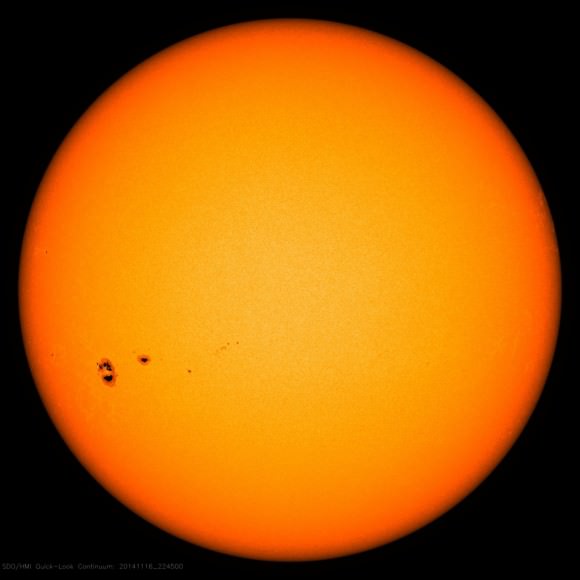

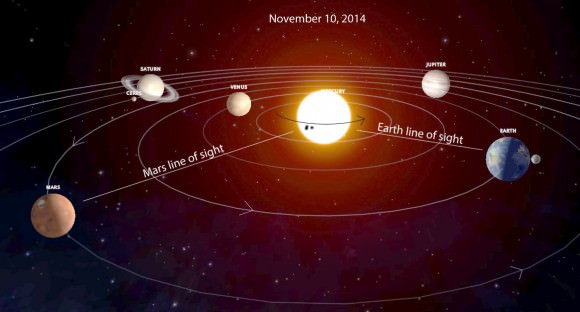

Prowling through the Curiosity raw image files, I came across this photo of the Sun on November 10th. Three dark spots at the left are immediately obvious and a dead-ringer for Active Region 2192, now re-named 2209 as it rounds the Sun for Act II. You’ll recall this was the sunspot group that nearly stole the show during the October 23rd partial solar eclipse. From Mars’ perspective, which currently allows Curiosity to see further around the solar “backside”, AR 2209 showed up a few days before it was visible from Earth.

Although it’s slimmed down in size, the region is still large enough to view with the naked eye through a safe solar filter. More importantly, it possesses a complex beta-gamma-delta magnetic field where magnetic north and south poles are in close proximity and ripe for reconnection and production of M-class and X-class flares. Already, the region’s crackled with three moderate M-class flares over the past two days. In no mood to take a back seat, AR 2209 continues to dominate solar activity even during round two.

Mars possesses two small moons, Deimos and Phobos. Curiosity has photographed them both before including an occultation Deimos (9 miles/15 km) by the larger Phobos (13.5 miles/22 km). Phobos orbits closer to Mars than any other moon does to its primary in the Solar System, just 3,700 miles (6,000 km). As a result, it moves too fast for Mars’ rotation to overtake it the way Earth’s rotation overtakes the slower-moving Moon, causing it to set in the west overnight. Contrarian Phobos rises in the western sky and sets in the east just 4 hours 15 minutes later. When nearest the horizon and farthest from an observer, it’s apparent size is just 0.14º. At the zenith it grows to 0.20º of 1/3 the diameter of the Moon.

One longish observing session on the planet would cover a complete rise-set cycle during which Phobos would first appear as a crescent and finish up a full moon a few hours later. All this talk about Phobos is only meant to direct you to the picture above taken by Curiosity on October 20, 2014 when the moon was a thick crescent. As on Earth, where Earthshine fills out the remainder of the crescent Moon, so too does Mars-shine provide enough illumination to see the full outline of Phobos.

Curiosity has also photographed Earth, sunsets and transits of Phobos across the Sun while rambling across the dusty red landscape since August 2012. Before we depart, it seems only fair to aim our gaze Mars-ward again to see what’s up. Or down. The rover’s been doing a geological “Walkabout” in the Pahrump Hills outcrop at the base of Mt. Sharp in Gale Crater since September. Earlier this fall it drilled and sampled rock there containing more hematite than at any of its previous stops. Hematite is an iron oxide that’s often associated with water.

The mission may spend weeks or months at the outcrop looking for and drilling new target rocks before moving further up the geological layer cake better known as Mt. Sharp.