One of the most interesting topics in the field of science is the concept of General Relativity. You know, this idea that strange things happen as you near the speed of light. There are strange changes to the length of things, bizarre shifting of wavelengths. And most puzzling of all, there’s the concept of dilation: how you can literally experience more or less time based on how fast you’re traveling compared to someone else.

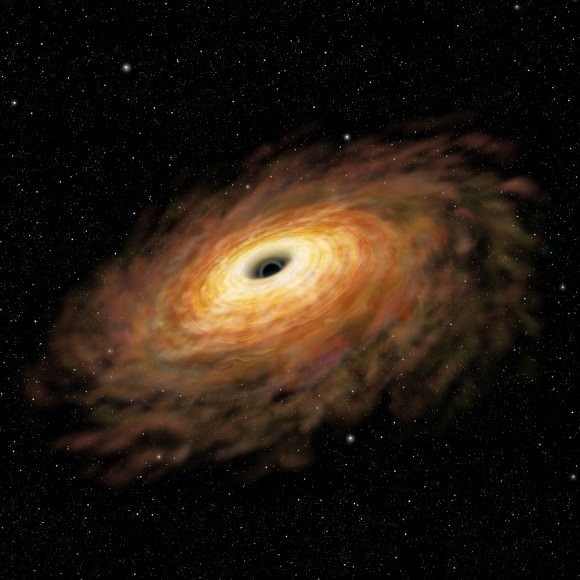

And even stranger than that? As we saw in the movie Interstellar, just spending time near a very massive object, like a black hole, can cause these same relativistic effects. Because mass and acceleration are sort of the same thing?

Honestly, it’s enough to give you a massive headache.

But just because I find the concept baffling, I’m still going to keep chipping away, trying to understand more about it and help you wrap your brain around it too. For my own benefit, for your benefit, but mostly for my benefit.

There’s a great anecdote in the history of physics – it’s probably not what actually happened, but I still love it.

One of the most famous astronomers of the 20th century was Sir Arthur Eddington, played by a dashing David Tennant in the 2008 movie, Einstein and Eddington. Which, you should really see, if you haven’t already.

So anyway, Doctor Who, I mean Eddington, had worked out how stars generate energy (through fusion) and personally confirmed that Einstein’s predictions of General Relativity were correct when he observed a total Solar Eclipse in 1919.

Apparently during a lecture by Sir Arthur Eddington, someone asked, “Professor Eddington, you must be one of the three people in the world who understands General Relativity.” He paused for a moment, and then said, “yes, but I’m trying to think of who the third person is.”

It’s definitely not me, but I know someone who does have a handle on General Relativity, and that’s Dr. Brian Koberlein, an astrophysics professor at the Rochester Institute of Technology. He covers this topic all the time on his blog, One Universe At A Time, which you should totally visit and read at briankoberlein.com.

In fact, just to demonstrate how this works, Brian has conveniently pushed his RIT office to nearly light speed, and is hurtling towards us right now.

Dr. Brian Koberlein:

Hi Fraser, thanks for having me. If you can hang on one second, I just have to slow down.

Fraser Cain:

What just happened there? Why were you all slowed down?

Brian:

It’s actually an interesting effect known as time dilation. One of the things about light is that no matter what frame of reference you’re in, no matter how you’re moving through the Universe, you’ll always measure the speed of light in a vacuum to be the same. About 300,000 kilometres per second.

And in order to do that, if you are moving relative to me, or if I’m moving relative to you, our references for time and space have to shift to keep the speed of light constant. As I move faster away from you, my time according to you has to appear to slow down. On the same hand, your time will appear to slow down relative to me.

And that time dilation effect is necessary to keep the speed of light constant.

Fraser:

Does this only happen when you’re moving?

Brian:

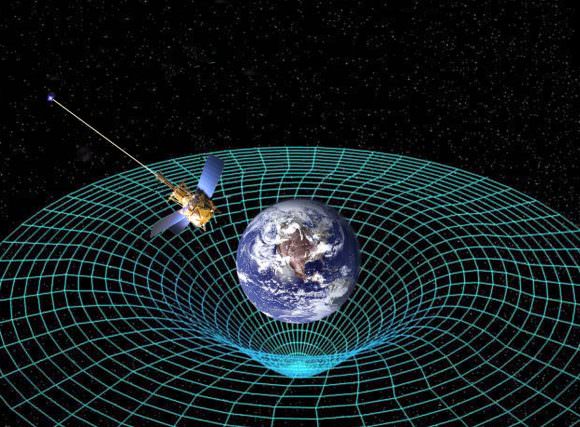

Time dilation doesn’t just occur because of relative motion, it can also occur because of gravity. Einstein’s theory of relativity says that gravity is a property of the warping of space and time. So when you have a mass like Earth, it actually warps space and time.

If you’re standing on the Earth, your time appears to move a little bit more slowly than someone up in space, because of the difference in gravity.

Now, for Earth, that doesn’t really matter that much, but for something like a black hole, it could matter a great deal. As you get closer and closer to a black hole, your time will appear to slow down more and more and more.

Fraser:

What would this mean for space travel?

Brian:

In many times in science fiction, you’ll see the idea of a rocket moving very close to the speed of light, and using time dilation to travel to distant stars.

But you could actually do the same thing with gravity. If you had a black hole that was going out to another star or another galaxy, you could actually take your spaceship and orbit it very close to the black hole. And your time would seem to slow down. While you’re orbiting the black hole, the black hole would take its time to get to another star or another galaxy, and for you it would seem really quick.

So that’s another way that you could use time dilation to travel to the stars, at least in science fiction.

Fraser:

All right Brian, I’ve got one final question for you. If you get more massive as you get closer to the speed of light, could you get so much mass that you turn into a black hole? I’d like you to answer this question in the form of a blog post on briankoberlein.com and on the Google+ post we’re going to link right here.

Brian:

Thanks Fraser, I’ll have that answer up on my website.

Once again, we visited the baffling realm of time dilation, and returned relatively unscathed. It doesn’t mean that I understand it any better, but I hope you do, anyway. Once again, a big thanks to Dr. Koberlein for taking a few minutes out of his relativistic travel to answer our questions. Make sure you visit his blog and read his answer to my question.