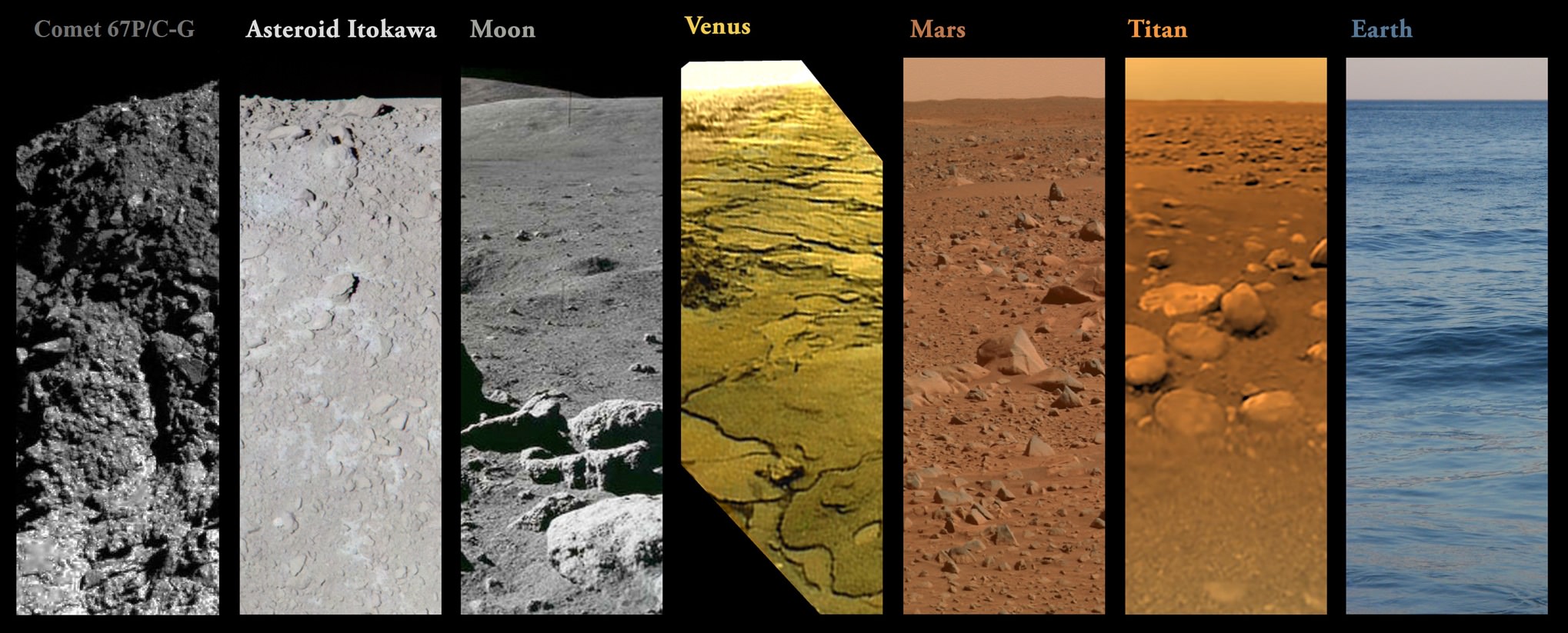

Think of all the different horizons humans have viewed on other worlds. The dust-filled skies of Mars. The Moon’s inky darkness. Titan’s orange haze. These are just a small subset of the worlds that humans or our robots landed on since the Space Age began.

It’s a mighty tribute to human imagination and engineering that we’ve managed to get to all these places, from moons to planets to comets and asteroids. By the way, for the most part we are going to focus on “soft landings” rather than impacts — so, for example, we wouldn’t count Galileo’s death plunge into Jupiter in 2003, or the series of planned landers on Mars that ended up crashing instead.

The Moon

Our instant first association with landings on other worlds is the human landings on the Moon. While it looms large in NASA folklore, the Apollo landings only took place in a brief span of space history. Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin were the first crew (on Apollo 11) to make a sortie in 1969, and Apollo 17’s Gene Cernan and Jack Schmitt made the final set of moonwalks in 1972. (Read more: How Many People Have Walked on the Moon?)

But don’t forget all the robotic surveyors that came before and after. In 1959, the Soviet Union’s Luna 2 made the first impact on the lunar surface; the first soft landing came in 1966, with Luna 9. The United States set a series of Ranger and Surveyor probes to reach the moon in the 1960s and 1970s. The Soviet Union also deployed a rover on the moon, Lunakhod 1, in 1970 — the first remote-controlled robot controlled on another world’s surface.

In 2013, China made the first lunar soft landing in a generation. The country’s Chang’e-3 not only made it safely, but deployed the Yutu rover shortly afterwards.

Mars

Mars is a popular destination for spacecraft, but only a fraction of those machines that tried to get there actually safely made it to the surface. The first successful soft landing came on Dec. 2, 1971 when the Soviet Union’s Mars 3 made it to the surface. The spacecraft, however, only transmitted for 20 seconds — perhaps due to dust storms on the planet’s surface.

Less than five years later, on July 20, 1976, NASA’s Viking 1 touched down on Chryse Planitia. This was quickly followed by its twin Viking 2 in September. NASA has actually made all the other soft landings to date, and expanded its exploration by using rovers to move around on the surface. The first one was Sojourner, a rover that rolled off the Pathfinder lander in 1997.

NASA also sent a pair of Mars Exploration Rovers in 2004. Spirit transmitted information back to Earth until 2010, while Opportunity is still roaming the surface. The more massive Curiosity lander followed them in 2012. Another stationary spacecraft, Phoenix, successfully landed close to the planet’s north pole in 2008.

Venus

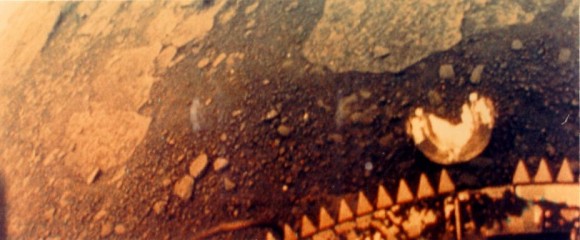

Venera 7 — one of a series of Soviet probes sent in the 1960s and 1970s — was the first to make it to the surface of Venus and send data back, on Dec. 15, 1970. It lasted 23 minutes on the surface, transmitting weakly towards Earth. This may have been because it came to rest on its side after bouncing through a landing.

The first pictures of the surface came courtesy of Venera 9, which made it to Venus on Oct. 22, 1975 and sent data back for 53 minutes. Venera 10 also successfully landed three days later and sent back data from Venus as planned. Several other Venera probes followed, most notably including Venera 13 — which sent back the first color images and remained active for 127 minutes.

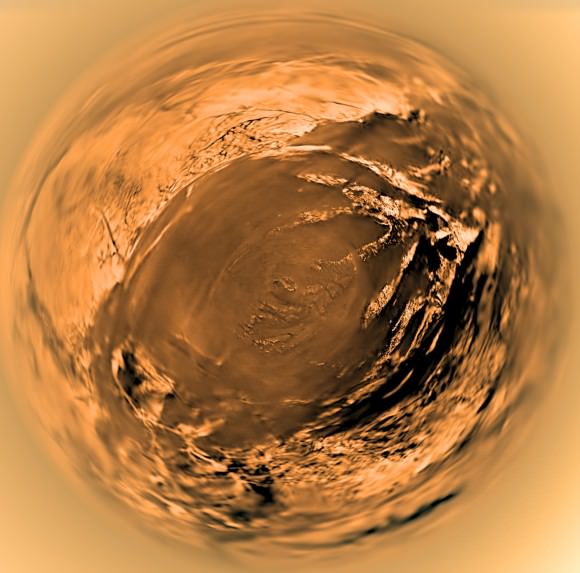

Titan

Humanity’s first and only landing on Titan so far came on Jan. 14, 2005. The European Space Agency’s Huygens probe likely didn’t come to rest right away when it arrived on the surface, bouncing and skidding for about 10 seconds after landing, an analysis showed almost a decade later.

The probe managed to send back information all the way through its 2.5-hour descent, and continued transmitting data for an hour and 12 minutes after landing. Besides the pictures, it also sent back information about the moon’s wind and surface.

The orangey moon of Saturn has come under scrutiny because it is believed to have elements in its atmosphere and on its surface that are precursors to life. It also has lakes of ethane and methane on its surface, showing that it has a liquid cycle similar to our own planet.

Comets and asteroids

Robots have also touched the ground on smaller, airless bodies in our Solar System — specifically, a comet and two asteroids. NASA’s NEAR Shoemaker made the first landing on asteroid Eros on Feb. 12, 2001, even though the spacecraft wasn’t even designed to do so. While no images were sent back from the surface, it did transmit data successfully for more than two weeks.

Japan made its first landing on an extraterrestrial surface on Nov. 19, 2005, when the Hayabusa spacecraft successfully touched down on asteroid Itokawa. (This followed a failed attempt to send a small hopper/lander, called Minerva, from Hayabusa on Nov. 12.) Incredibly, Hayabusa not only made it to the surface, but took off again to return the samples to Earth — a feat it accomplished successfully in 2010.

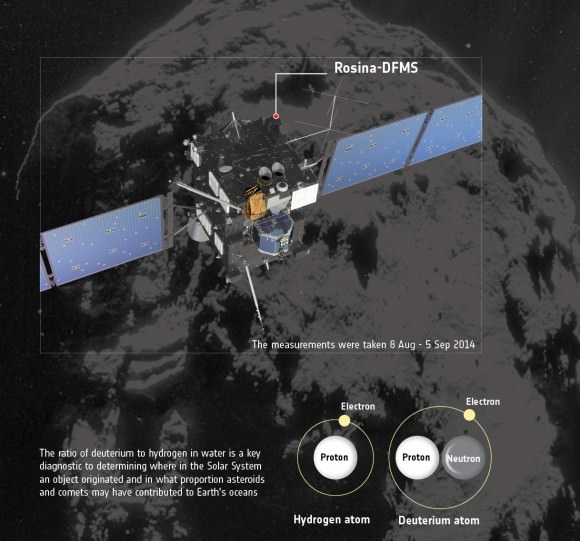

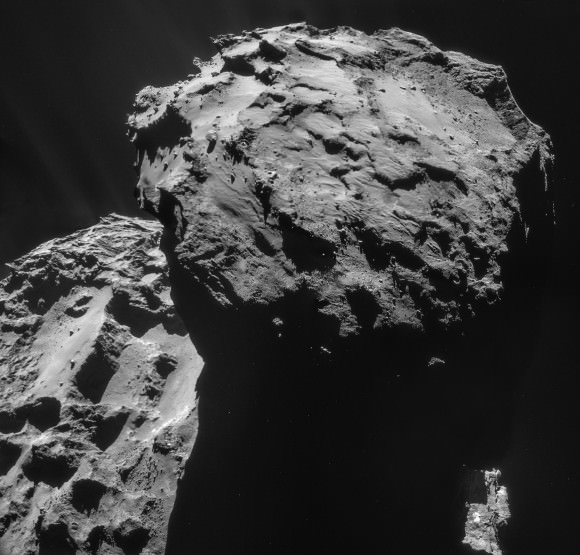

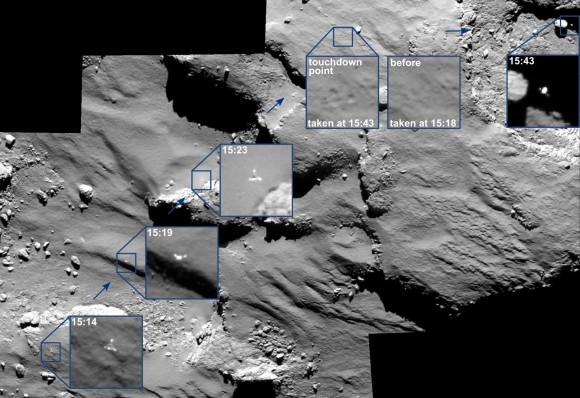

The first comet landing came on Nov. 12, 2014 when the European Space Agency’s Philae lander successfully separated from the Rosetta orbiter and touched the surface of Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko. Philae’s harpoons failed to deploy as planned and the lander drifted for more than two hours from its planned landing site until it stopped in a relatively shady spot on the comet’s surface. Its batteries drained after a few days and the probe fell silent. As of early 2015, controllers are hoping that as more sunlight reaches 67P by mid-year, Philae will wake up again.