Yesterday evening you may have dropped by to watch Slooh’s live coverage of asteroid 2000 EM26 as it passed just 8.8 lunar distances of Earth. Surprise – the space rock never showed up! Slooh’s robotic telescope attempted to recover the asteroid and share its speedy travels with the world but failed to capture an image at the predicted position.

Now nicknamed Moby Dick after the elusive whale in Herman Melville’s novel of the same name, the asteroid’s gone missing in the deep sea of space. Earthlings need fear no peril; it’s not headed in our direction anytime soon. Either the asteroid’s predicted path was in error or the object was much fainter than expected. More likely the former.

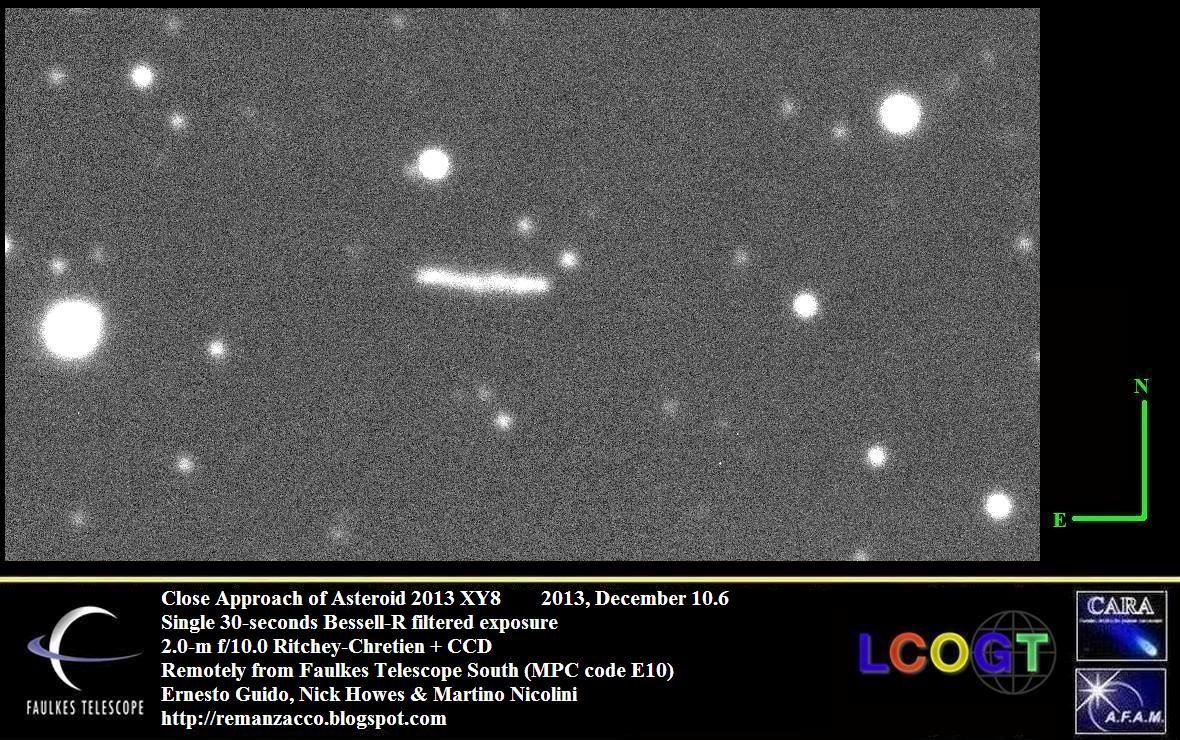

Last night’s coverage attempt of 2000 E26’s close flyby of Earth

2000 EM26’s predicted brightness at the time was around magnitude 15.4, not bright but well within range of the telescope. Rather than throwing their hands up in the air, the folks at Slooh are calling upon amateur astronomers make a photographic search for the errant space rock in the next few nights.

Since the asteroid was last observed 14 years ago for only 9 days, it isn’t too surprising that uncertainties in its position could add up over time, shifting the asteroid’s position and path to a different part of the sky by 2014. According to Daniel Fischer, German amateur astronomer and astronomy writer, the positions were off by 100 degrees! As Paul Cox, Slooh’s Observatory Director, points out:

“Discovering these Near Earth Objects isn’t enough. As we’ve seen with 2000 EM26, all the effort that went into its discovery is worthless unless followup observations are made to accurately determine their orbits for the future. And that’s exactly what Slooh members are doing, using the robotic telescopes at our world-class observatory site to accurately measure the precise positions of these asteroids and comets.”

If a determined, modern-day Ahab doesn’t find this asteroidal Moby Dick, one of the large scale robotic telescope surveys probably will. Here’s a link to the NASA/JPL particulars including brightness, coordinates and distance for 2000 EM26.

Similar sized asteroids, including ones passing even closer to Earth, zip by every month. 2000 EM26 received a lot of coverage yesterday likely because it arrived near the time of the anniversary of the Chelyabinsk meteorite fall over Russia. Though it remains scarce for now, eyes are on the sky to find the asteroid again and refine its orbit. Hopefully the beast won’t get away next time.

Check out the lively discussion going on at Asteroid and Comet Researcher List. More information HERE.