[/caption]

The first asteroid to have been spotted before hitting Earth, 2008 TC3, crashed in northern Sudan one year ago on October 6. Several astronomers have been trying to piece together a profile of this asteroid, pulling together information from meteorites found at the impact site and the images captured of the object in the hours before it crashed to Earth.

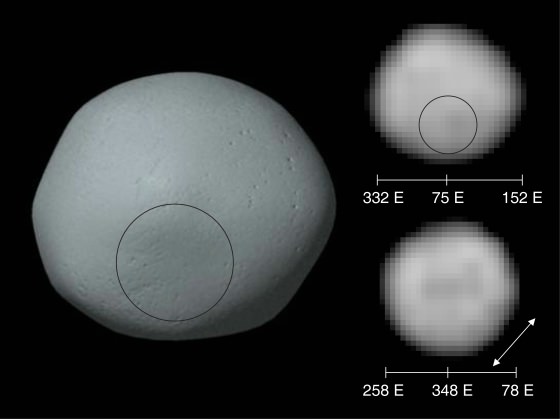

“We have a gigantic jigsaw puzzle on our hands, from which we try to create a picture of the asteroid and its origins,” said SETI Institute astronomer Peter Jenniskens, who worked at the crash site, “and now we have with a composite sketch of the culprit, cleverly using the eyewitness accounts of astronomers that saw the asteroid sneak up on us.” Their description? 2008 TC3 looked like a loaf of walnut-raisin bread.

“The asteroid now has a face,” said Jenniskens, chair of the special session at the fall meeting for the Division for Planetary Sciences of the American Astronomical Society. Last December, Jenniskens and Sudan astronomer Muawia Shaddad went to the crash site and recovered 300 fragments in the Nubian Desert. Like detectives, students from the University of Khartoum helped sweep the desert to look for remains of the asteroid. They found many different-looking meteorites close to, but a little south, of the calculated impact trajectory.

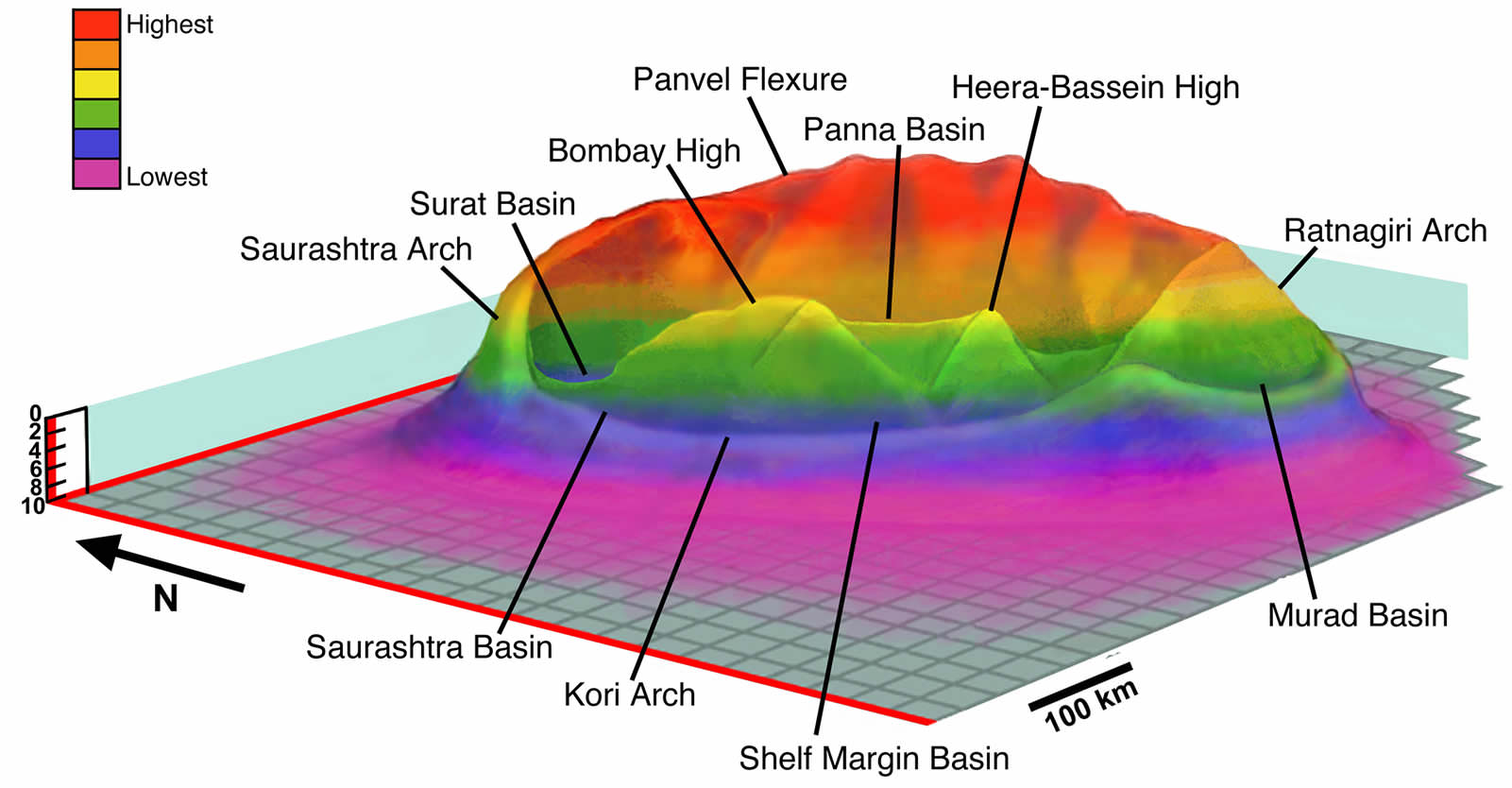

The team has also been able to recreate the shape of the asteroid from looking at images captured by Astronomers Marek Kozubal and Ron Dantowitz of the Clay Center Observatory in Brookline, Massachusetts, who tracked the asteroid with a telescope and captured the flicker of light during a two hour period just before impact.

An irregular shape and rapid tumbling caused asteroid 2008 TC3 to flicker when it reflected sunlight on approach to Earth.

Peter Scheirich and colleagues at Ondrejov Observatory and Charles University in the Czech Republic combined all the various observations to work out the shape and orientation of the asteroid.

Watch a video recreation of 2008 TC3 tumbling in space.

Larger version. (1.32 MB Mpeg 4 file)

Video of 2008 TC3 as seen through a telescope (large file, 7.63 MB)

Other forensic evidence based on analysis of the recovered meteorites at the Almahata Sitta site showed the asteroid was an unusual “polymict ureilite” type. Jason S. Herrin of NASA’s Johnson Space Center confirmed that the meteorites still carry traces of being heated to 1150-1300 degrees C, before rapidly cooling down at a rate of tens of degrees C per hour, during which carbon in the asteroid turned part of the olivine mineral iron into metallic iron. Hence, asteroid 2008 TC3 is the remains of a minor planet that endured massive collisions billions of years ago, melting some of the minerals, but not all, before a final collision shattered the planet into asteroids.

Mike Zolensky of NASA’s Johnson Space Center first pointed out that, as far as ureilites are concerned, his meteorite is unusually rich in pores, with pore walls coated by crystals of the mineral olivine. He now reports, from X-ray tomography work with Jon Friedrich of Fordham University in New York, that those pores appear to outline grains that have been incompletely welded together and that the pore linings appear to be vapor phase deposits. According to Zolensky, “Almahata Sitta may represent an agglomeration of coarse- to fine-grained, incompletely reduced pellets formed during impact, and subsequently welded together at high temperature.”

The carbon in the recovered meteorites is among the most cooked of all known meteorites. Carbon crystals of graphite and nanodiamonds have been detected. Still, it turns out that some of the organic matter in the original material survived the heating. Amy Morrow, Hassan Sabbah, and Richard Zare of Stanford University have found polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in high abundances. Amazingly, Michael Callahan and colleagues of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center now report that even some amino acids have survived.

Jenniskens and Shaddad plan to revisit the scene of the crash in the Nubian Desert. They reported their findings at the Division for Planetary Sciences of the American Astronomical Society meeting in Puerto Rico.

Listen to Oct. 6th’s 365 Days of Astronomy podcast by Emily Lakdawalla about 2008 TC3.

Source: AAS Planetary Science Division