[/caption]

In the famous words of Arthur C. Clarke, “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” This phrase is often quoted to express the idea that an alien civilization which may be thousands or millions of years older than us would have technology so far ahead of ours that to us it would appear to be “magic.”

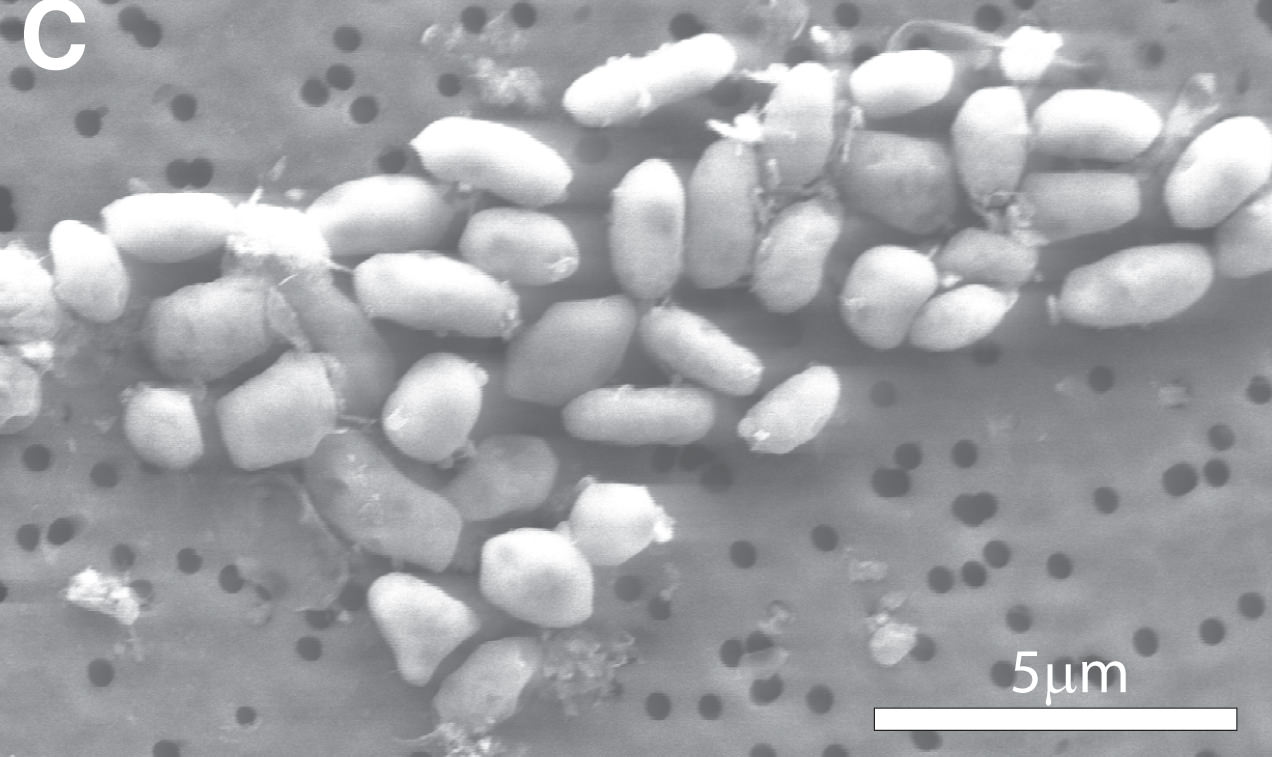

Now, a variation of that thought has come from Canadian science fiction writer Karl Schroeder, who posits that “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from nature.” The reasoning is that if a civilization manages to exist that long, it would inevitably “go green” to such an extent that it would no longer leave any detectable waste products behind. Its artificial signatures would blend in with those of the natural universe, making it much more difficult to detect them by simply searching for artificial constructs versus natural ones.

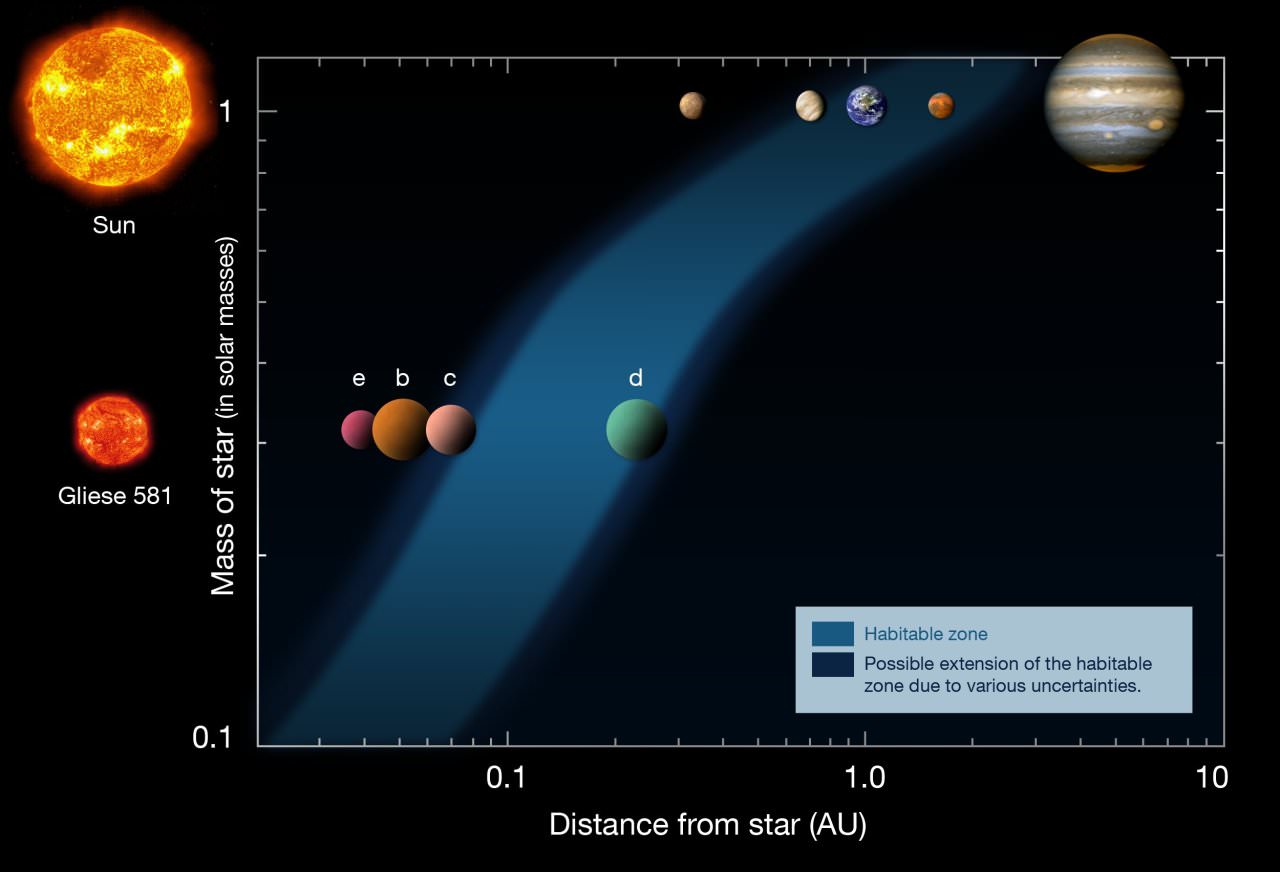

The idea has been proposed as an explanation for why we haven’t found them yet, based on the premise that such advanced societies would have visited and colonized our entire galaxy by now (known as the Fermi Paradox). The question becomes more interesting in light of the fact that astronomers now estimate that there are billions of other planets in our galaxy alone. If a civilization reaches such a “balance with nature” as a natural progression, it may mean that traditional methods of searching for them, like SETI, will ultimately fail. Of course, it is possible, perhaps even likely, that civilizations much older than us would have advanced far beyond radio technology anyway. SETI itself is based on the assumption that some of them may still be using that technology. Another branch of SETI is searching for light pulses such as intentional beacons as opposed to radio signals.

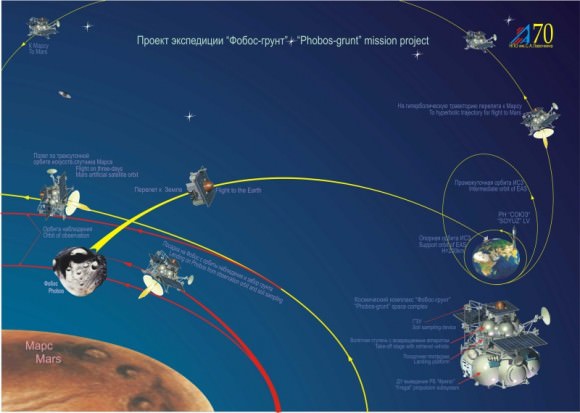

But even other alternate searches, such as SETT (Search for Extraterrestrial Technology), may not pan out either, if this new scenario is correct. SETT looks for things like the spectral signature of nuclear fission waste being dumped into a star, or leaking tritium from alien fusion powerplants.

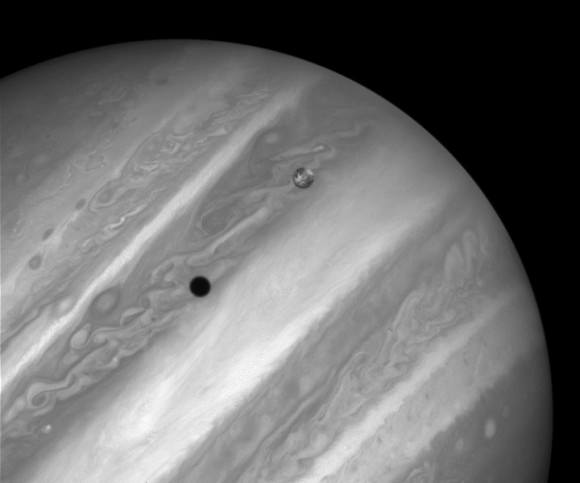

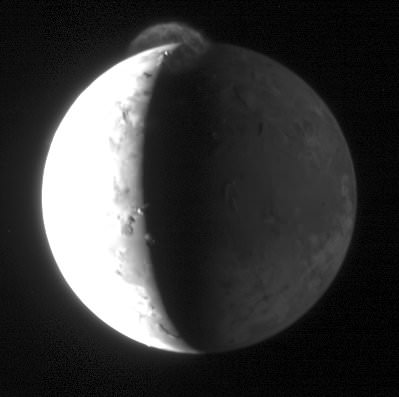

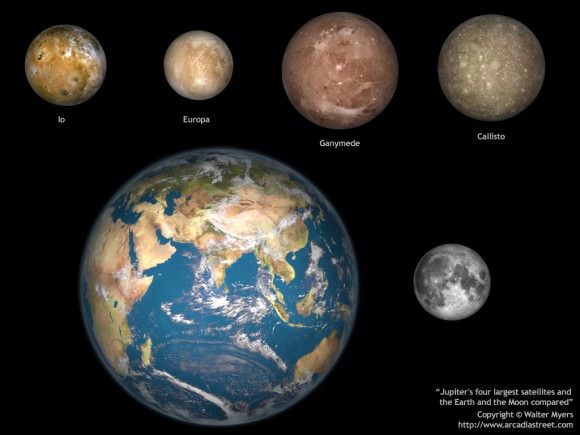

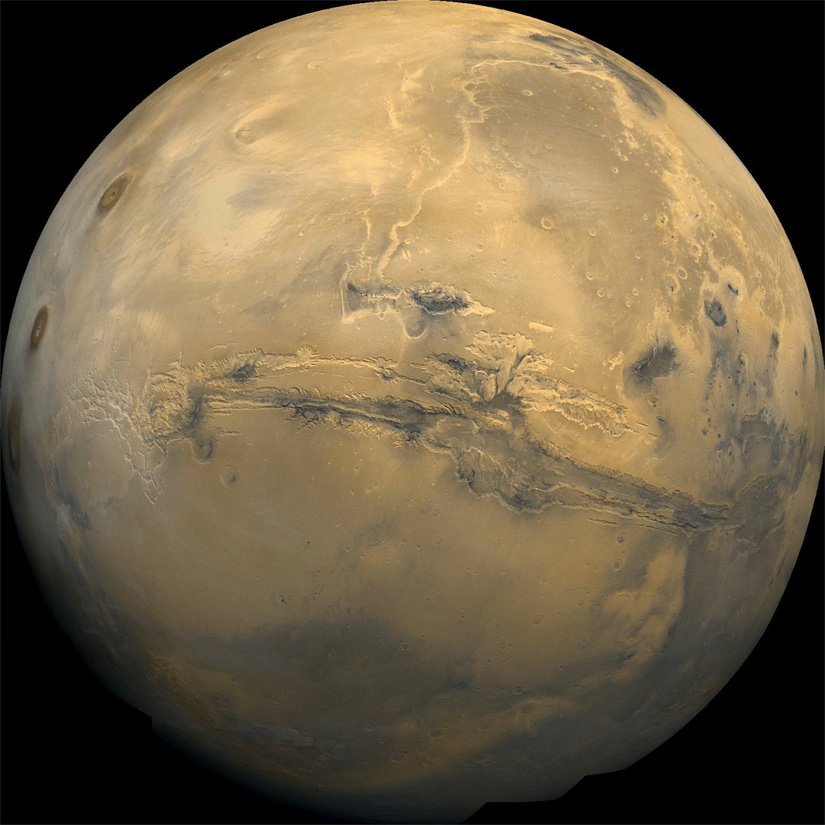

Another solution to the Fermi Paradox states that advanced civilizations will ultimately destroy themselves. Before they do though, they could have already sent out robotic probes to many places in the galaxy. If those probes were technologically savvy enough to self-replicate, they could have spread themselves widely across the cosmos. If there were any in our solar system, we could conceivably find them. Yet this idea could also come back around to the new hypothesis – if these probes were advanced enough to be truly “green” and not leave any environmental traces, they might be a lot harder to find, blending in with natural objects in the solar system.

It’s an intriguing new take on an old question. It can also be taken as a lesson – if we can learn to survive our own technological advances long enough, we can ultimately become more of a green civilization ourselves, co-existing comfortably with the natural universe around us.