Since the early days of the internet, and even computers more generally, there has been a push to collect all of the world’s information, built up over thousands of years, into a digital form so it can at least theoretically latest indefinitely. It also makes that information much more accessible to people interested in it. That was the motto of the original Google search engine, and specialists in various historical fields have been making slow but steady progress in doing just that over the past few decades. Now astronomy has gained one of its largest hauls of historical data as the Friedrich-Alexander University of Erlangen-Nuremberg has digitized 40,000 of its historical astronomical plates, along with 54,090 plates from other sources.

Continue reading “Astronomers Have Digitized 94,000 Photographic Plates of the Night sky, Going Back 129 Years”Low-Cost Approach to Scanning Historic Glass Plates Yields an Astronomical Surprise

A new process highlights an innovative way to get old glass plates online… and turned up a potential extra-galactic discovery over a century old.

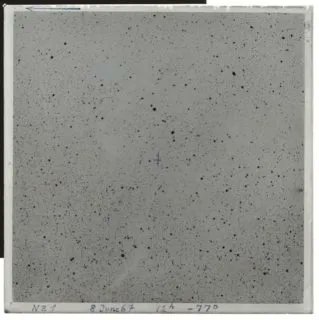

You never know what new discoveries might be hiding in old astronomical observations. For almost a hundred years starting in the late 19th century, emulsion-coated dry glass plate photography was the standard of choice used by large astronomical observatories and surveys for documenting and imaging the sky. These large enormous glass plate collections are still out there around the world, filed away in observatory libraries and university archives. Now, a new project shows how we might bring the stories told on these old plates back to light.

Continue reading “Low-Cost Approach to Scanning Historic Glass Plates Yields an Astronomical Surprise”Calling All Volunteers to Help Digitize Astronomical History

An old brick building on Harvard’s Observatory Hill is overflowing with rows of dark green cabinets — each one filled to the brim with hundreds of astronomical glass plates in paper sleeves: old-fashioned photographic negatives of the night sky.

All in all there are more than 500,000 plates preserving roughly a century of information about faint happenings across the celestial sphere. But they’re gathering dust. So the Harvard College Observatory is digitizing its famed collection of glass plates. One by one, each plate is placed on a scanner capable of measuring the position of each tiny speck to within 11 microns. The finished produce will lead to one million gigabytes of data.

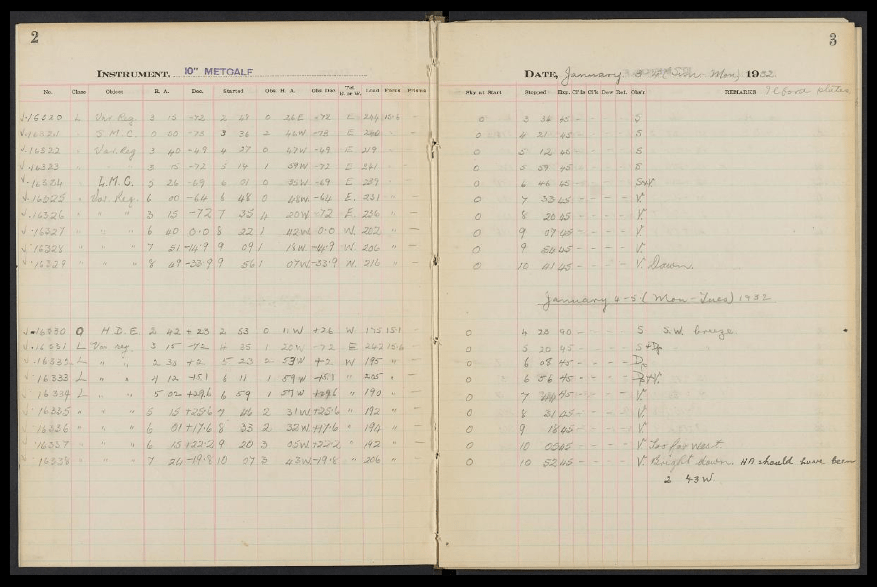

But each plate must be linked to a telescope logbook — handwritten entries recording details like the date, time, exposure length, and location in the sky. Now, Harvard is seeking your help to transcribe these logbooks.

The initial project is called Digital Access to a Sky Century at Harvard (DASCH). Although it has been hard at work scanning roughly 400 plates per day, without the logbook entries to accompany each digitized plate, information about the brightness and position of each object would be lost. Whereas with that information it will be possible to see a 100-year light curve of any bright object within 15 degrees of the north galactic pole.

The century of data allows astronomers to detect slow variations over decades, something otherwise impossible in today’s recent digital era.

Assistant Curator David Sliski is especially excited about the potential overlap in our hunt for exoplanets. “It covers the Kepler field beautifully,” Sliski told Universe Today. It should also be completed by the time next-generation exoplanet missions (such as TESS, PLATO, and Kepler 2) come online — allowing astronomers to look for long-term variability in a host star that may potentially affect an exoplanet’s habitability.

There are more than 100 logbooks containing about 100,000 pages of text. Volunteers will type in a few numbers per line of text onto web-based forms. It’s a task impossible for any scanner since optical character recognition doesn’t work on these hand-written entries.

Harvard is partnering with the Smithsonian Transcription Center to recruit digital volunteers. The two will then be able to bring the historic documents to a new, global audience via the web. To participate in this new initiative, visit Smithsonian’s transcription site here.