Just when we think we understand the Universe pretty well, along come some astronomers to upend everything. In this case, something essential to everything we know and see has been turned on its head: the expansion rate of the Universe itself, aka the Hubble Constant.

A team of astronomers using the Hubble telescope has determined that the rate of expansion is between five and nine percent faster than previously measured. The Hubble Constant is not some curiousity that can be shelved until the next advances in measurement. It is part and parcel of the very nature of everything in existence.

“This surprising finding may be an important clue to understanding those mysterious parts of the universe that make up 95 percent of everything and don’t emit light, such as dark energy, dark matter, and dark radiation,” said study leader and Nobel Laureate Adam Riess of the Space Telescope Science Institute and The Johns Hopkins University, both in Baltimore, Maryland.

But before we get into the consequences of this study, let’s back up a bit and look at how the Hubble Constant is measured.

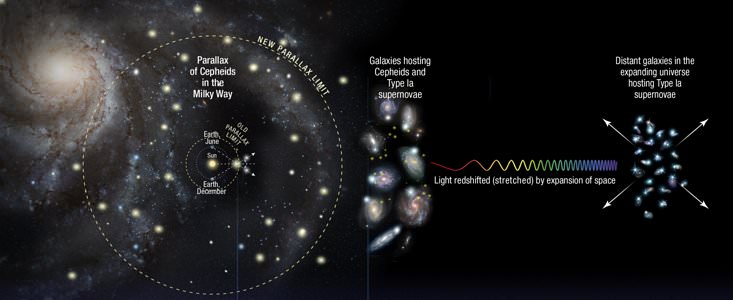

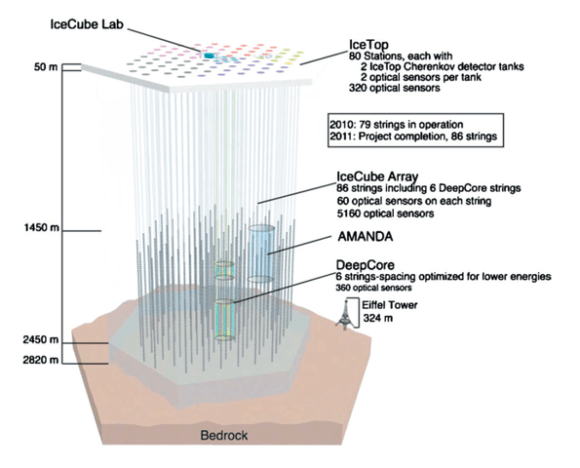

Measuring the expansion rate of the Universe is a tricky business. Using the image at the top, it works like this:

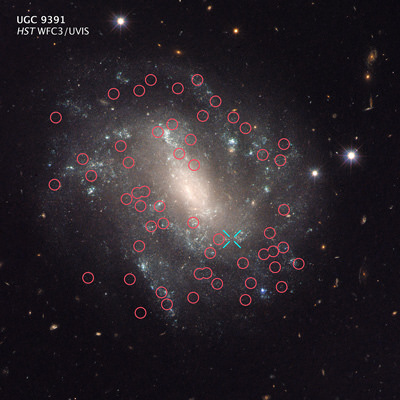

- Within the Milky Way, the Hubble telescope is used to measure the distance to Cepheid variables, a type of pulsating star. Parallax is used to do this, and parallax is a basic tool of geometry, which is also used in surveying. Astronomers know what the true brightness of Cepheids are, so comparing that to their apparent brightness from Earth gives an accurate measurement of the distance between the star and us. Their rate of pulsation also fine tunes the distance calculation. Cepheid variables are sometimes called “cosmic yardsticks” for this reason.

- Then astronomers turn their sights on other nearby galaxies which contain not only Cepheid variables, but also Type 1a supernova, another well-understood type of star. These supernovae, which are of course exploding stars, are another reliable yardstick for astronomers. The distance to these galaxies is obtained by using the Cepheids to measure the true brightness of the supernovae.

- Next, astronomers point the Hubble at galaxies that are even further away. These ones are so distant, that any Cepheids in those galaxies cannot be seen. But Type 1a supernovae are so bright that they can be seen, even at these enormous distances. Then, astronomers compare the true and apparent brightnesses of the supernovae to measure out to the distance where the expansion of the Universe can be seen. The light from the distant supernovae is “red-shifted”, or stretched, by the expansion of space. When the measured distance is compared with the red-shift of the light, it yields a measurement of the rate of the expansion of the Universe.

- Take a deep breath and read all that again.

The great part of all of this is that we have an even more accurate measurement of the rate of expansion of the Universe. The uncertainty in the measurement is down to 2.4%. The challenging part is that this rate of expansion of the modern Universe doesn’t jive with the measurement from the early Universe.

The rate of expansion of the early Universe is obtained from the left over radiation from the Big Bang. When that cosmic afterglow is measured by NASA’s Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) and the ESA’s Planck satellite, it yields a smaller rate of expansion. So the two don’t line up. It’s like building a bridge, where construction starts at both ends and should line up by the time you get to the middle. (Caveat: I have no idea if bridges are built like that.)

“You start at two ends, and you expect to meet in the middle if all of your drawings are right and your measurements are right,” Riess said. “But now the ends are not quite meeting in the middle and we want to know why.”

“If we know the initial amounts of stuff in the universe, such as dark energy and dark matter, and we have the physics correct, then you can go from a measurement at the time shortly after the big bang and use that understanding to predict how fast the universe should be expanding today,” said Riess. “However, if this discrepancy holds up, it appears we may not have the right understanding, and it changes how big the Hubble constant should be today.”

Why it doesn’t all add up is the fun, and maybe maddening, part of this.

What we call Dark Energy is the force that drives the expansion of the Universe. Is Dark Energy growing stronger? Or how about Dark Matter, which comprises most of the mass in the Universe. We know we don’t know much about it. Maybe we know even less than that, and its nature is changing over time.

“We know so little about the dark parts of the universe, it’s important to measure how they push and pull on space over cosmic history,” said Lucas Macri of Texas A&M University in College Station, a key collaborator on the study.

The team is still working with the Hubble to reduce the uncertainty in measurements of the rate of expansion. Instruments like the James Webb Space Telescope and the European Extremely Large Telescope might help to refine the measurement even more, and help address this compelling issue.