Over 5,000 exoplanets have been discovered around distant star systems. Protoplanetary disks have been discovered too and it’s these, out of which all planetary systems form. Such disks have recently been found in two binary star systems. The stellar components in one have a separation of 14 astronomical units (the average distance between the Earth and Sun is one astronomical unit) and the other system has a separation of 22 astronomical units. Studying systems like these allow us to see how the stars of a binary system interact and how they can distort protoplanetary disks.

Continue reading “Astronomers See Planets Forming Around Binary Stars”Sometimes Compact Galaxies Hide Their Black Holes

Quasars, short for quasi-stellar objects, are one of the most powerful and luminous classes of objects in our Universe. A subclass of active galactic nuclei (AGNs), quasars are extremely bright galactic cores that temporarily outshine all the stars in their disks. This is due to the supermassive black holes in the galactic cores that consume material from their accretion disks, a donut-shaped ring of gas and dust that orbit them. This matter is accelerated to close to the speed of light and slowly consumed, releasing energy across the entire electromagnetic spectrum.

Based on past observations, it is well known to astronomers that quasars are obscured by the accretion disk that surrounds them. As powerful radiation is released from the SMBH, it causes the dust and gas to glow brightly in visible light, X-rays, gamma-rays, and other wavelengths. However, according to a new study led by researchers from the Centre for Extragalactic Astronomy (CEA) at Durham University, quasars can also be obscured by the gas and dust of their entire host galaxies. Their findings could help astronomers better understand the link between SMBHs and galactic evolution.

Continue reading “Sometimes Compact Galaxies Hide Their Black Holes”Astronomers Find a Newly-Forming Quadruple-Star System

In a surprising find, the international ALMA Survey of Orion Planck Galactic Cold Clumps (ALMASOP) team recently observed a young quadruple star system within a star-forming region in the Orion constellation. The discovery was made during a high-resolution survey of 72 dense cores in the Orion Giant Molecular Clouds (GMCs) using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile. These observations provide a compelling explanation for the origins and formation mechanisms of binary and multiple-star systems.

Continue reading “Astronomers Find a Newly-Forming Quadruple-Star System”Unusual Distributions of Organics Found in Titan’s Atmosphere

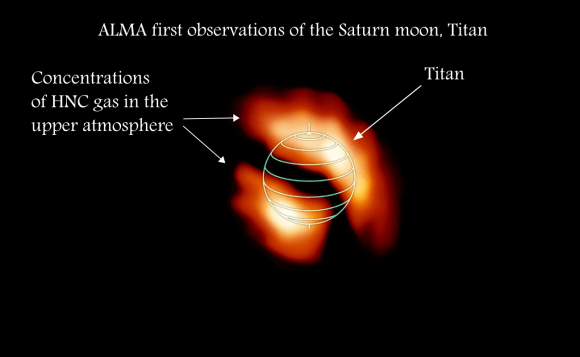

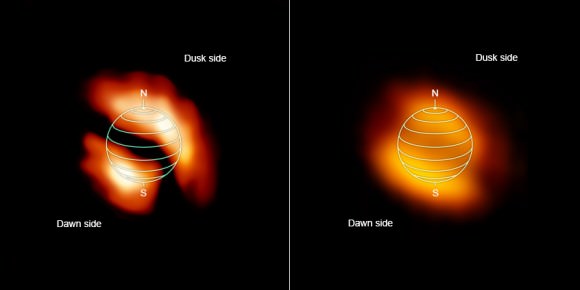

A new mystery of Titan has been uncovered by astronomers using their latest asset in the high altitude desert of Chile. Using the now fully deployed Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA) telescope in Chile, astronomers moved from observing comets to Titan. A single 3 minute observation revealed organic molecules that are askew in the atmosphere of Titan. The molecules in question should be smoothly distributed across the atmosphere, but they are not.

The Cassini/Huygens spacecraft at the Saturn system has been revealing the oddities of Titan to us, with its lakes and rain clouds of methane, and an atmosphere thicker than Earth’s. But the new observations by ALMA of Titan underscore how much more can be learned about Titan and also how incredible the ALMA array is.

The ALMA astronomers called it a “brief 3 minute snapshot of Titan.” They found zones of organic molecules offset from the Titan polar regions. The molecules observed were hydrogen isocyanide (HNC) and cyanoacetylene (HC3N). It is a complete surprise to the astrochemist Martin Cordiner from NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. Cordiner is the lead author of the work published in the latest release of Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The NASA Goddard press release states, “At the highest altitudes, the gas pockets appeared to be shifted away from the poles. These off-pole locations are unexpected because the fast-moving winds in Titan’s middle atmosphere move in an east–west direction, forming zones similar to Jupiter’s bands, though much less pronounced. Within each zone, the atmospheric gases should, for the most part, be thoroughly mixed.”

When one hears there is a strange, skewed combination of organic compounds somewhere, the first thing to come to mind is life. However, the astrochemists in this study are not concluding that they found a signature of life. There are, in fact, other explanations that involve simpler forces of nature. The Sun and Saturn’s magnetic field deliver light and energized particles to Titan’s atmosphere. This energy causes the formation of complex organics in the Titan atmosphere. But how these two molecules – HNC and HC3N – came to have a skewed distribution is, as the astrochemists said, “very intriguing.” Cordiner stated, “This is an unexpected and potentially groundbreaking discovery… a fascinating new problem.”

The press release from the National Radio Astronomy Observatory states, “studying this complex chemistry may provide insights into the properties of Earth’s very early atmosphere.” Additionally, the new observations add to understanding Titan – a second data point (after Earth) for understanding organics of exo-planets, which may number in the hundreds of billions beyond our solar system within our Milky Way galaxy. Astronomers need more data points in order to sift through the many exo-planets that will be observed and harbor organic compounds. With Titan and Earth, astronomers will have points of comparison to determine what is happening on distant exo-planets, whether it’s life or not.

(Image Credit: NRAO/AUI/NSF)

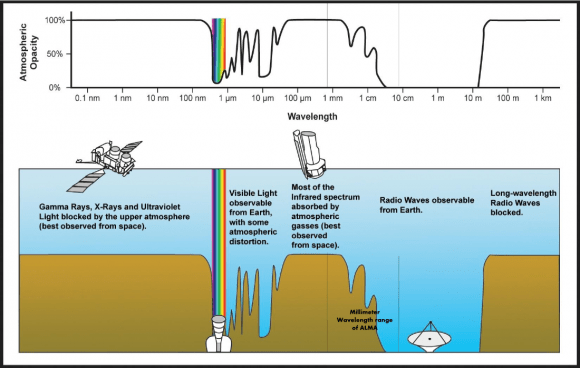

The report of this new and brief observation also underscores the new astronomical asset in the altitudes of Chile. ALMA represents the state of the art of millimeter and sub-millimeter astronomy. This field of astronomy holds a lot of promise. Back around 1980, at the Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona, alongside the great visible light telescopes, there was an oddity, a millimeter wavelength dish. That dish was the beginning of radio astronomy in the 1 – 10 millimeter wavelength range. Millimeter astronomy is only about 35 years old. These wavelengths stand at the edge of the far infrared and include many light emissions and absorptions from cold objects which often include molecules and particularly organics. The ALMA array has 10 times more resolving power than the Hubble space telescope.

The Earth’s atmosphere stands in the way of observing the Universe in these wavelengths. By no coincidence our eyes evolved to see in the visible light spectrum. It is a very narrow band, and it means that there is a great, wide world of light waves to explore with different detectors than just our eyes.

In the millimeter range of wavelengths, water, oxygen, and nitrogen are big absorbers. Some wavelengths in the millimeter range are completely absorbed. So there are windows in this range. ALMA is designed to look at those wavelengths that are accessible from the ground. The Chajnantor plateau in the Atacama desert at 5000 meters (16,400 ft) provides the driest, clearest location in the world for millimeter astronomy outside of the high altitude regions of the Antarctic.

At high altitude and over this particular desert, there is very little atmospheric water. ALMA consists of 66 12 meter (39 ft) and 7 meter (23 ft) dishes. However, it wasn’t just finding a good location that made ALMA. The 35 year history of millimeter-wavelength astronomy has been a catch up game. Detecting these wavelengths required very sensitive detectors – low noise in the electronics. The steady improvement in solid-state electronics from the late 70s to today and the development of cryostats to maintain low temperatures have made the new observations of Titan possible. These are observations that Cassini at 1000 kilometers from Titan could not do but ALMA at 1.25 billion kilometers (775 million miles) away could.

The ALMA telescope array was developed by a consortium of countries led by the United States’ National Science Foundation (NSF) and countries of the European Union though ESO (European Organisation for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere). The first concepts were proposed in 1999. Japan joined the consortium in 2001.

The prototype ALMA telescope was tested at the site of the VLA in New Mexico in 2003. That prototype now stands on Kitt Peak having replaced the original millimeter wavelength dish that started this branch of astronomy in the 1980s. The first dishes arrived in 2007 followed the next year by the huge transporters for moving each dish into place at such high altitude. The German-made transporter required a cabin with an oxygen supply so that the drivers could work in the rarefied air at 5000 meters. The transporter was featured on an episode of the program Monster Moves. By 2011, test observations were taking place, and by 2013 the first science program was undertaken. This year, the full array was in place and the second science program spawned the Titan observations. Many will follow. ALMA, which can operate 24 hours per day, will remain the most powerful instrument in its class for about 10 years when another array in Africa will come on line.

References:

“Alma Measurements Of The Hnc And Hc3N Distributions In Titan’s Atmosphere“, M. A. Cordiner, et al., Astrophysical Journal Letters

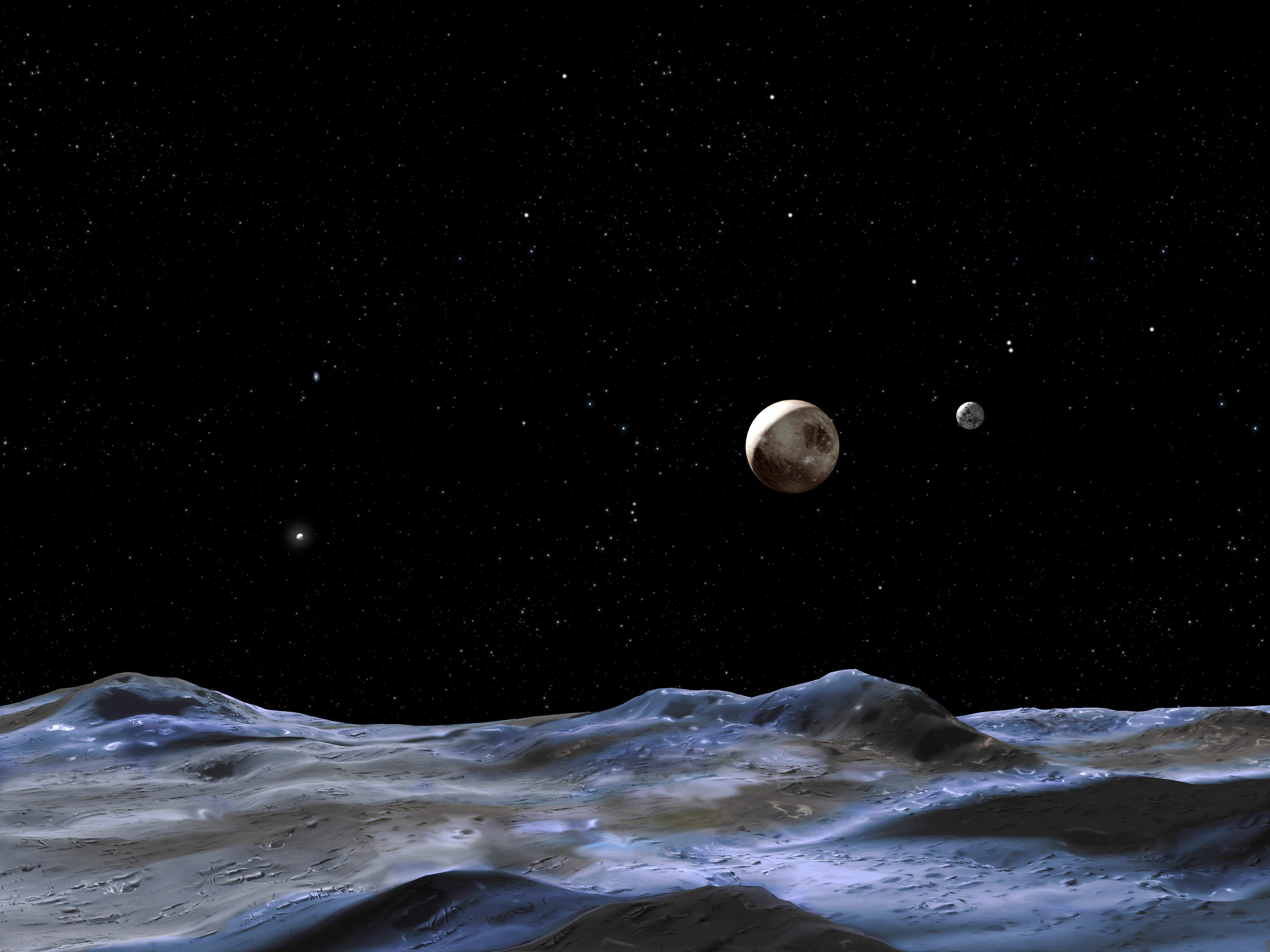

Where Exactly Is Pluto? Pinpoint Precision Needed For New Horizons Mission

When you have a spacecraft that takes the better part of a decade to get to its destination, it’s really, really important to make sure you have an accurate fix on where it’s supposed to be. That’s true of the Rosetta spacecraft (which reached its comet today) and also for New Horizons, which will make a flyby past Pluto in 2015.

To make sure New Horizons doesn’t miss its big date, astronomers are using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) to figure out its location and orbit around the Sun. You’d think that we’d know where Pluto is after decades of observations, but because it’s so far away we’ve only tracked it through one-third of its 248-year orbit.

“With these limited observational data, our knowledge of Pluto’s position could be wrong by several thousand kilometers, which compromises our ability to calculate efficient targeting maneuvers for the New Horizons spacecraft,” stated Hal Weaver, a New Horizons project scientist at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Maryland.

As ALMA is a radio/submillimeter telescope, the array picked up Pluto and its largest moon, Charon, by looking at the radio emission from their surfaces. They examined the objects in November 2013, in April 2014 and twice in July. More observations are expected in October.

“By taking multiple observations at different dates, we allow Earth to move along its orbit, offering different vantage points in relation to the Sun,” stated Ed Fomalont, an astronomer with the National Radio Astronomy Observatory who is assigned to ALMA’s operations support facility in Chile. “Astronomers can then better determine Pluto’s distance and orbit.”

New Horizons will reach Pluto in July 2015, and Universe Today is planning a series of articles about the dwarf planet. We’ll need your support to get it done, though. Check out the details here.

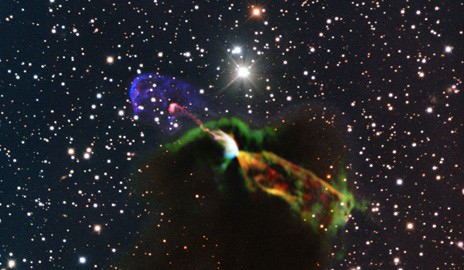

Supersonic Starbirth Bubble Glows In Image From Two Telescopes

Talk about birth in the fast lane. Fresh observations of HH 46/47 — an area well-known for hosting a baby star — demonstrate material from the star pushing against the surrounding gas at supersonic speeds.

“HH” stands for Herbig-Haro, a type of object created “when jets shot out by newborn stars collide with surrounding material, producing small, bright, nebulous regions,” NASA stated. It’s a little hard to see what’s inside these regions, however, as they’re clouded by debris (specifically, gas and dust).

The Spitzer space telescope (which looks in infrared) and the massive Chilean Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) are both designed to look through the stuff to see what’s within. Here’s what they’ve spotted:

– ALMA: The telescope is showing that the gas is moving apart faster than ever believed, which could have echoes on how the star cloud is forming generally. “In turn, the extra turbulence could have an impact on whether and how other stars might form in this gaseous, dusty, and thus fertile, ground for star-making,” NASA added.

– Spitzer: Two supersonic blobs are emerging from the star in the middle and pushing against the gas, creating the big bubbles you can see here. The right-aiming blob has a lot more material to push through than the left one, “offering a handy compare-and-contrast setup for how the outflows from a developing star interact with their surroundings,” NASA stated.

“Young stars like our sun need to remove some of the gas collapsing in on them to become stable, and HH 46/47 is an excellent laboratory for studying this outflow process,” stated Alberto Noriega-Crespo, a scientist at the Infrared Processing and Analysis Center at the California Institute of Technology.

“Thanks to Spitzer, the HH 46/47 outflow is considered one of the best examples of a jet being present with an expanding bubble-like structure.”

The ALMA observations of HH 46/47 were first revealed in detail this summer, in an Astrophysical Journal publication.

Source: NASA