[/caption]

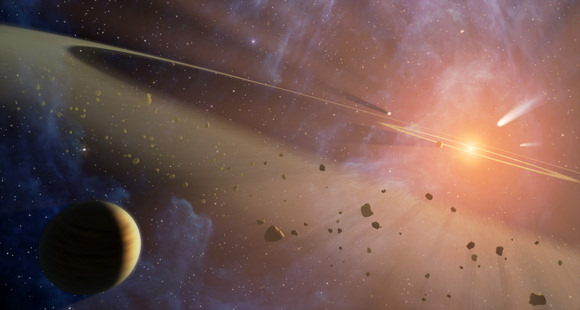

A new study finds the gases which formed the Earth’s atmosphere – as well as its oceans – did not come from inside the Earth but from comets and meteorites hitting Earth during the Late Heavy Bombardment period. A research team tested volcanic gases to uncover the new evidence. “We found a clear meteorite signature in volcanic gases,” said Dr. Greg Holland the project’s lead scientist. “From that we now know that the volcanic gases could not have contributed in any significant way to the Earth’s atmosphere. Therefore the atmosphere and oceans must have come from somewhere else, possibly from a late bombardment of gas and water rich materials similar to comets.”

Holland said textbook images of ancient Earth with huge volcanoes spewing gas into the atmosphere will have to be rethought.

According to the theory of the Late Heavy Bombardment, the inner solar system was pounded by a sudden rain of solar system debris only 700 million years after it formed, which likely had monumental effects on the nascent Earth. So far, the evidence for this event comes primarily from the dating of lunar samples, which indicates that most impact melt rocks formed in this very narrow interval of time. But this new research on the origin of Earth’s atmosphere may lend credence to this theory as well.

The researchers analyzed the krypton and xenon found in upper-mantle gases leaking from the Bravo Dome gas field in New Mexico. They found that the two noble gases have isotopic signatures characteristic of early Solar System material similar to me teorites instead of the modern atmosphere and oceans. It therefore appears that noble gases trapped within the young Earth did not contribute to Earth’s later atmosphere.

The study is also the first to establish the precise composition of the Krypton present in the Earth’s mantle.

“Until now, no one has had instruments capable of looking for these subtle signatures in samples from inside the Earth – but now we can do exactly that,” said Holland.

The team’s research, “Meteorite Kr in Earth’s Mantle Suggests a Late Accretionary Source for the Atmosphere” was published in the journal Science.

Sources: Science, EurekAlert