[/caption]

There’s oxygen around Dione, a research team led by scientists at New Mexico’s Los Alamos National Laboratory announced on Friday. The presence of molecular oxygen around Dione creates an intriguing possibility for organic compounds — the building blocks of life — to exist on other outer planet moons.

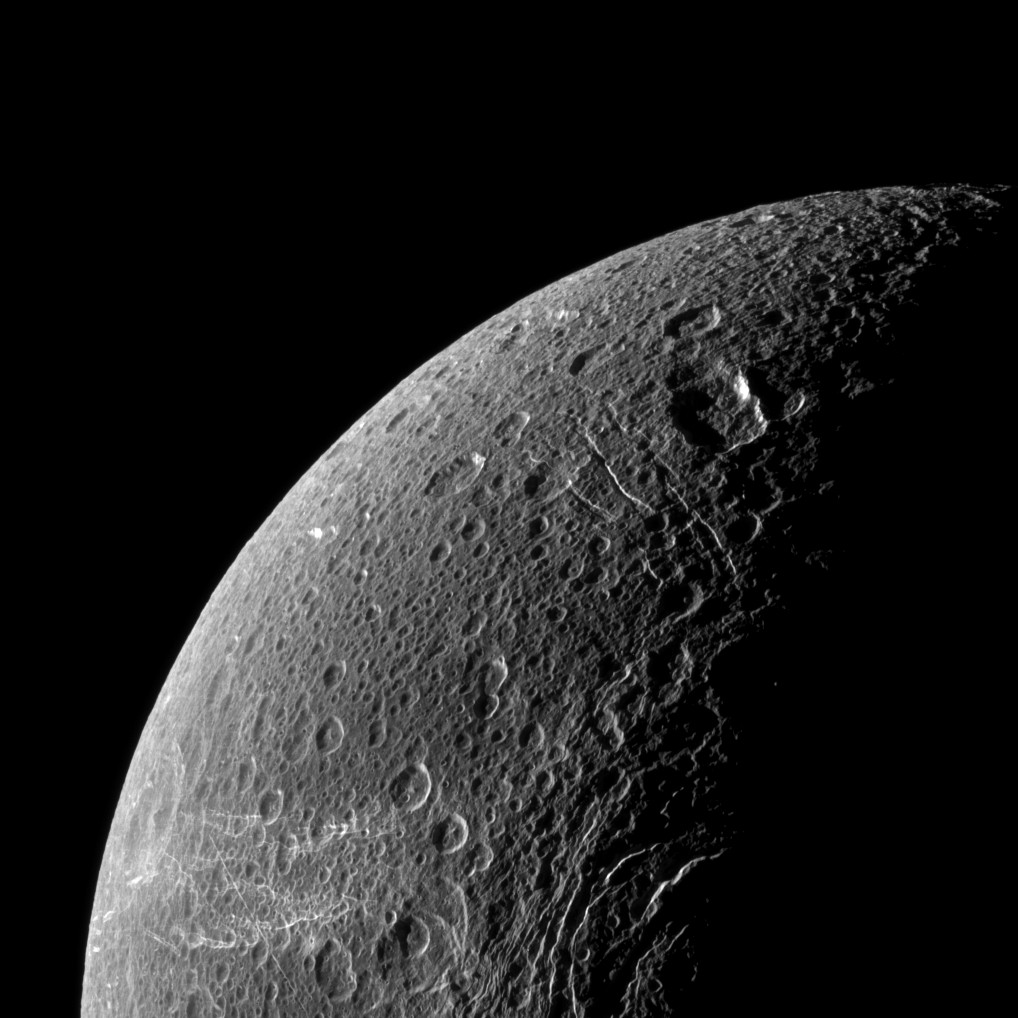

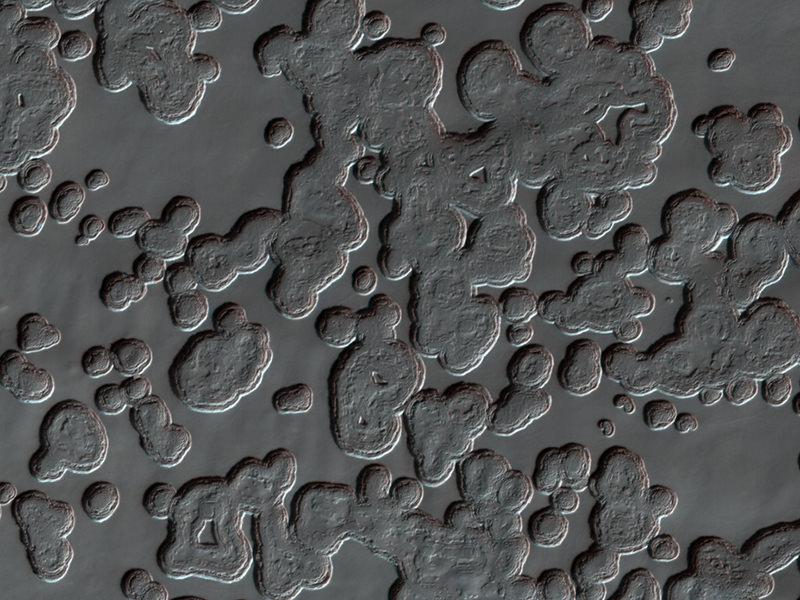

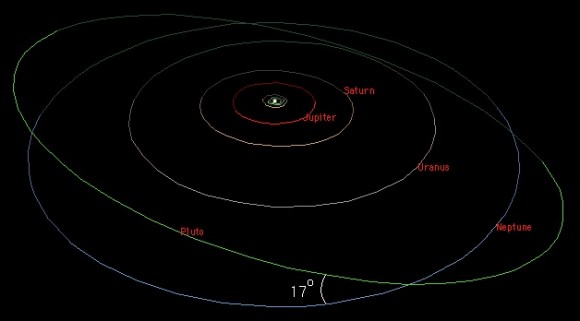

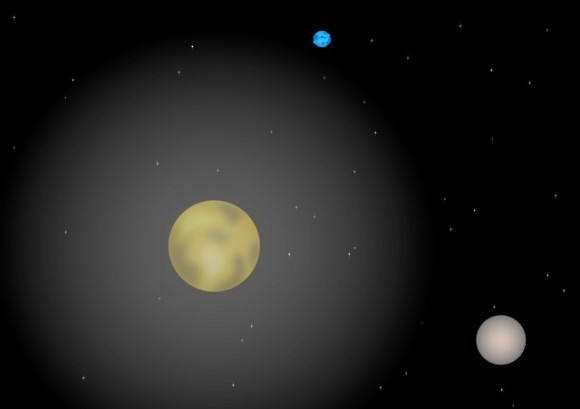

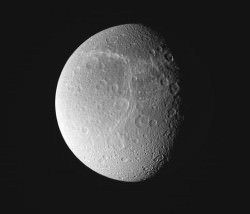

One of Saturn’s 62 known moons, Dione (pronounced DEE-oh-nee) is 698 miles (1,123 km) in diameter. It orbits Saturn at about the same distance that our Moon orbits Earth. Heavily cratered and crisscrossed by long, bright scarps, Dione is made mostly of water ice and rock. It makes a complete orbit of Saturn every 2.7 days.

Data acquired during a flyby of the moon by the Cassini spacecraft in 2010 have been found by the Los Alamos researchers to confirm the presence of molecular oxygen high in Dione’s extremely thin atmosphere — so thin, in fact, that scientists prefer the term exosphere.

While you couldn’t take a deep breath on Dione, the presence of O2 indicates a dynamic process in action.

“The concentration of oxygen in Dione’s atmosphere is roughly similar to what you would find in Earth’s atmosphere at an altitude of about 300 miles,” said Robert Tokar, researcher at Los Alamos National Laboratory and lead author of the paper published in Geophysical Research Letters. “It’s not enough to sustain life, but—together with similar observations of other moons around Saturn and Jupiter—these are definitive examples of a process by which a lot of oxygen can be produced in icy celestial bodies that are bombarded by charged particles or photons from the Sun or whatever light source happens to be nearby.”

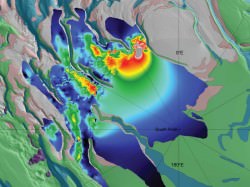

On Dione the energy source is Saturn’s powerful magnetic field. As the moon orbits the giant planet, charged ions in Saturn’s magnetosphere slam into the surface of Dione, stripping oxygen from the ice on its surface and crust. This molecular oxygen (O2) flows into Dione’s exosphere, where it is then steadily blown into space by — once again — Saturn’s magnetic field.

Cassini’s instruments detected the oxygen in Dione’s wake during an April 2010 flyby.

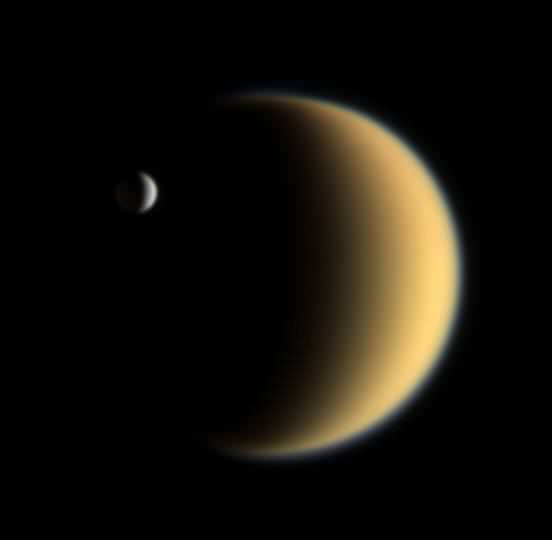

Molecular oxygen, if present on other moons as well (say, Europa or Enceladus) could potentially bond with carbon in subsurface water to form the building blocks of life. Since there’s lots of water ice on moons in the outer solar system, as well as some very powerful magnetic fields emanating from planets like Jupiter and Saturn, there’s no reason to think there isn’t more oxygen to be found… in our solar system or elsewhere.

Read the news release from the Los Alamos National Laboratory here.

Image credits: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute. Research citation: Tokar, R. L., R. E. Johnson, M. F. Thomsen, E. C. Sittler, A. J. Coates, R. J. Wilson, F. J. Crary, D. T. Young, and G. H. Jones (2012), Detection of exospheric O2+ at Saturn’s moon Dione, Geophys. Res. Lett., 39, L03105, doi:10.1029/2011GL050452.